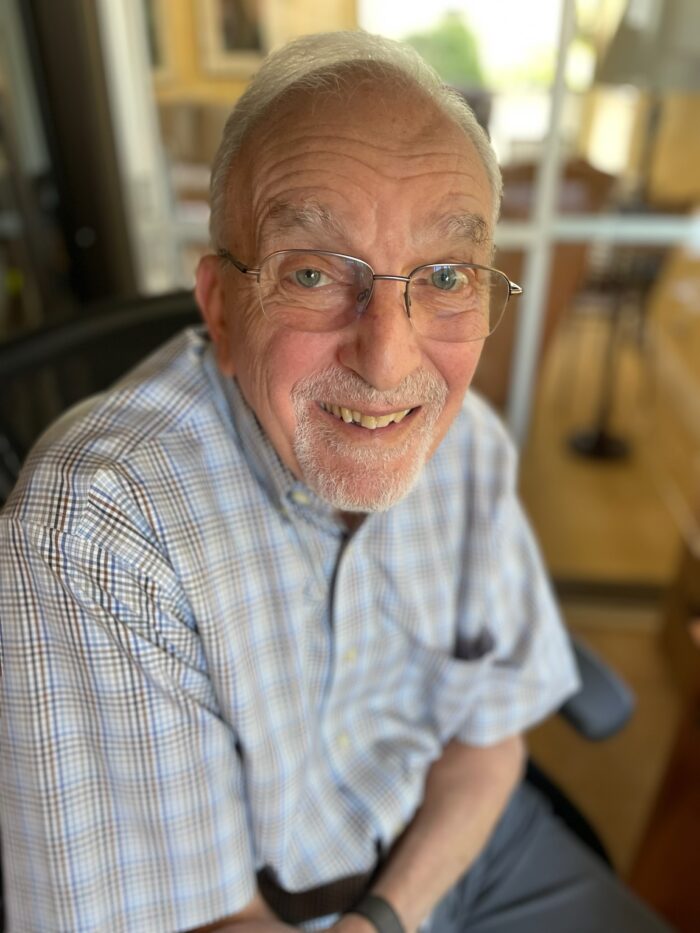

Albert “Al” Martin, a key architect behind the California Health Care Foundation’s renowned leadership training program, died on May 21, 2025, from complications of Parkinson’s Disease. He was 87.

The Harvard-trained physician devoted his career to public health, and his interest in improving health care delivery, especially among historically marginalized populations, led him to take leadership roles as an advocate. He worked at the UCSF internal medicine training program and in medical leadership at Harvard Community Health Plan, Blue Shield of California, and other major health care organizations.

One of Martin’s enduring legacies came after he retired and took on the work of helping design and implement CHCF’s innovative Health Care Leadership Program, which trains health care clinicians in management skills not taught in schools for health professionals. The program, launched in 2001, aimed to sharpen its students’ leadership capacities so they could take on high impact work in the industry. The program continues today, and its 665 alumni have gone on to serve in health care leadership roles in state government, hospitals, Medi-Cal managed care plans, community health centers, and other types of organizations.

The two-year, part time fellowship, led by national experts in health care and leadership development from UCSF’s Healthforce Center, coaches cohorts of clinicians each year in tactics to address health care issues from the perspectives of business management and public policy. The goal is for them to apply these skills in real time within their home organizations.

“Al Martin reimagined California health care as an ecosystem managed not just by business executives but increasingly by doctors, nurses, and other clinicians,” said Sandra R. Hernández, MD, President and CEO of the California Health Care Foundation. “Al co-designed a brilliant program that has continued without interruption for nearly a quarter century. Thanks to his vision and dedication, hundreds of clinicians have become transformative leaders, improving care for countless Californians.”

Martin, who chaired the advisory committee, helped envision the program and craft the curriculum alongside founders Ed O’Neil, PhD, and CHCF’s former president and CEO, Mark Smith, MD. O’Neil, who served as the program’s director until he retired in 2012, said Martin’s insights and background helped infuse the fellowship with a focus on interprofessional collaboration, health equity, and relationship building.

“He had this great sensitivity to trying to understand the realities of big, complex health systems and bringing a kind of humanity to that,” O’Neil said.

The project was hugely important to Martin, said his wife, Diana Richmond. “Designing the leadership program engaged all of Al’s immense breadth and curiosity, and his interaction with the teams lit him up,” she said. “It was such a pleasure to witness him at work in this capacity.”

Giving Clinicians Management Skills

The program set out to help transform the health care industry in the late 1990s, when many health organizations were helmed by executives without medical backgrounds, and prepare experienced clinicians for a seat at the table.

At the time, many of these clinicians didn’t have the management experience necessary to excel in these roles. Despite extensive schooling in medicine, their training typically didn’t involve matters such as balancing a spreadsheet or handling human resources complaints — skills that are all too necessary as a health care leader.

Susan Fleischman, part of the fellowship’s first cohort in 2001, said leadership training helped her learn the skills and vocabulary she needed to collaborate with other executives. At the time, she was medical director at Venice Family Clinic, a free clinic in Los Angeles that was growing rapidly. She was doing her best to stay afloat.

“I didn’t have an MPH, I didn’t have an MBA, I didn’t have a law degree,” Fleischman said. “I was doing all this new stuff, and kind of winging it.”

As a fellow, she received mentorship and guidance in everything from financial management to public speaking, not to mention camaraderie and fellowship with intellectual peers. She made friends with whom she’s remained in touch to this day.

Confidence to Take On New Roles

Fleischman, who is now retired, said the program helped her at Venice Family Clinic but it also gave her the confidence to make a move to roles with more responsibility. She went on to serve at a number of high-profile organizations including Kaiser Foundation Health Plan, where she served as Vice President of Medicaid, strategizing how to deliver care to low-income patients across the country. As her career progressed, she was able to leverage both her management skills alongside her medical background. Fleischman persuaded several colleagues to complete the fellowship in later years.

“It’s important to have physician leadership in the health care industry,” she said. “I mean, it is health care, right? We’re not making widgets.”

David Reuben, who also trained in Cohort 1, stayed at his health organization and said it gave him the confidence to take on national leadership roles within his industry. Reuben, former chief of UCLA’s geriatric division, later served as president of the American Geriatric Society, where he acted as a spokesperson for US geriatricians, and chair of the board of directors for the American Board of Internal Medicine.

Teacher as Student

The fellowship helped him understand himself better on a personal level as well. Motivated by an assignment during the program to come up with a project that had “nothing to do with work,” Reuben ended up writing a play, Reprieves, which explored end-of-life care through the eyes of an elderly patient who survived a catastrophic fall but not its aftermath. The play was featured at a playwrights’ festival and in readings, and in the two decades after it was produced, Reuben wrote 10 more plays.

“It was a life changing experience,” said Reuben, who returned to the program as an adviser. “My career trajectory would have been very different and, not that it wouldn’t have been good, not that I wouldn’t have done good work, but it brought me to a different level.”

Others worked to emulate aspects of Martin’s and the founders’ vision within their own health care curriculum.

Michael Wilkes, director of global health and a professor of internal medicine at UC Davis, said he was inspired by the CHCF program’s interdisciplinary orientation. He trained alongside nurses, pharmacists, dentists, social workers, and physicians from other specialties. He was vice dean of the UC Davis medical school at the time and observed that the students he oversaw learning to be physicians, physician assistants, or nurse practitioners – weren’t interacting in this way and had become siloed and competitive.

To that end, Wilkes put students from different programs together in small-group problem-solving sessions where they could learn from one other and see the benefits each profession brought to patients. Two decades later, that clinic is still in operation. Wilkes said it has been the most popular class in the medical school.

“Al showed me what was possible and how looking at some of these health problems from these different perspectives really was the only way to move from where we were to where we wanted to go,” Wilkes said.

‘The Soul of the Program’

Many alumni from the early cohorts remember Martin with reverence.

“Al was the soul of the program,” Reuben said. “He was there all the time. He was a shepherd for us.”

O’Neil, who worked for years alongside Martin, said that he was most influential in providing a template for how to be a new type of leader in health care. The fellows considered him intelligent yet humble, a thoughtful listener, and a compassionate mentor. O’Neil said he was consistently struck by Martin’s willingness to admit mistakes and welcome new perspectives — rare characteristics in the medical field at the time, especially for leaders like Martin who were at the top of their game.

“He was willing to not only be vulnerable, but to share it with people, and that was a great gift that he gave,” O’Neil said. “His humility, his candor, his openness — many of the fellows are better leaders today because they saw him exhibiting those behaviors.”

Authors & Contributors

Molly Castle Work, MJ

Independent Journalist

Molly Castle Work is an award-winning journalist based in Los Angeles. Her work has appeared in outlets like NPR, KFF Health News, the Los Angeles Times, and the Washington Post. She is a frequent guest on local NPR affiliate radio programs, such as LAist. She earned her master’s in journalism from the University of Maryland.