California Attorney General Xavier Becerra alleges that Sutter Health used its pre-eminent market power to artificially inflate prices. Photo: Rich Pedroncelli/Associated Press

UPDATE — OCTOBER 17, 2019: Sutter Health has reached a tentative settlement agreement with the state of California. Neither side has commented on the terms of the agreement, which must be approved by the court and could be made public during approval hearings in February or March.

As a jury trial draws near in a major class-action lawsuit alleging anticompetitive practices by Northern California’s largest health system (PDF), a new CHCF study shows the correlation between the prices consumers pay and the extensive consolidation in the state’s health care markets. Importantly, the researchers estimated the independent effect of several types of industry consolidation in California — such as health insurers buying other insurers and hospitals buying physician practices. The report, prepared by UC Berkeley researchers, also examines potential policy responses.

While other states have initiated antitrust complaints against large hospital systems and medical groups in the past, the case against Sutter Health is unique in both the expansive nature of the alleged conduct and in the scale of the potential monetary damages. The complaint goes beyond claims of explicit anticompetitive contract terms and argues that by virtue of its very size and structure, the Northern California system imposed implicit or “de facto” terms that led to artificially inflated prices. Sutter Health vigorously denies the allegations.

The formation of large health systems like Sutter is neither new (PDF) nor unique to California (PDF). Several factors seem to be encouraging their growth, including payment models that place health care providers at financial risk for the cost of care, increased expectations from policymakers and payers around the continuum of patient needs that must be managed, and economies of scale for investments in information technology and administrative services. Some market participants also point to consolidation in other parts of the health care system, such as health plans and physician groups, as encouragement for their own mergers.

Economic Consolidation in California

In general, economists study two major categories of market consolidation:

- Horizontal consolidation: Entities of the same type merge, such as the merger of two hospitals or insurance companies, or the merger of providers into a physician network.

- Vertical consolidation: Entities of different types merge, such as when a hospital purchases a physician practice or when a pharmacy buys an insurance company.

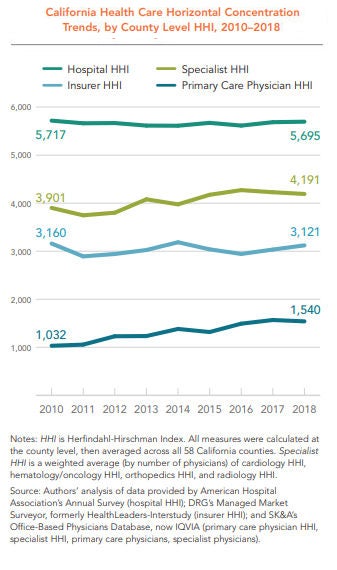

To measure market consolidation, the CHCF study relied on the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI), a metric used by the US Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission. An HHI of between 1,500 and 2,500 is considered moderately concentrated, and 2,500 or above is considered highly concentrated. According to this measure, horizontal concentration is high in California among hospitals, insurance companies, and specialist providers (and moderately high among primary care physicians), even though the level of concentration in all but primary care has remained relatively flat from 2010 to 2018.

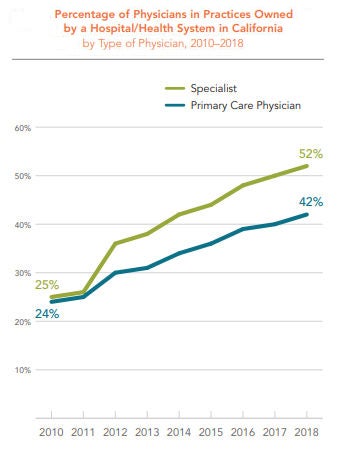

The percentage of physicians in practices owned by a hospital or health system increased dramatically in California between 2010 and 2018 — from 24% in 2010 to 42% in 2018. The percentage of specialists in practices owned by a hospital or health system rose even faster, from 25% in 2010 to 52% in 2018.

Consolidation Is Not Clinical Integration

While this study defined and quantified the extent of consolidation across several industry segments in California, it is important to note that it did not define, quantify, or evaluate clinical integration within the state. Clinical integration has been defined by others in many ways, but generally involves arrangements for coordinating and delivering a wide range of medical services across multiple settings.

As the CHCF study authors point out, other analysis has shown that various types of clinical integration can lead to broader adoption of health information technology and evidence-based care management processes. Data from the Integrated Healthcare Association suggests that certain patient benefit designs and provider risk-sharing arrangements associated with clinical integration can lead to higher quality and lower costs.

Crucially, an emerging body of law (PDF) suggests that clinical integration does not require formal ownership and joint bargaining with payers.

Relationship Between Consolidation and Health Insurance Premiums

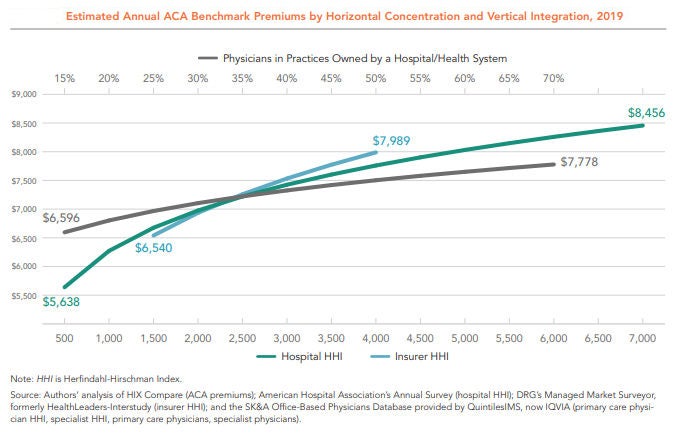

Among the six variables analyzed in the CHCF study, three showed a positive and statistically significant association with higher premiums: insurance company mergers, hospital mergers, and the percentage of primary care physicians in practices owned by hospitals and health systems. The remaining three variables studied — specialist provider mergers, primary care provider mergers, and the percentage of specialists in practices owned by a hospital and health system — were statistically insignificant.

The figure below shows the independent relationship between market concentration and premiums for these three variables. As the lines move left to right, concentration increases — that is, fewer individual insurers, hospitals, or providers occupy the market. The vertical axis shows the average premiums associated with each level of market concentration. In short, regardless of the industry structure represented by the other variables, insurer consolidation, hospital consolidation, and hospital-physician mergers each lead to higher premiums.

Unexplained Price Variation and Growth

Health insurance premiums rise when the underlying cost of medical care increases. California ranks as the 16th most expensive state on average in terms of the seven common services the researchers studied, after adjusting for wage differences across states. Among all states, California has the eighth-highest prices for normal childbirth, defined as vaginal delivery without complications. Childbirth is the most common type of hospital admission, and the relatively standardized procedure is comparable across states.

Even within California, prices vary widely and are growing rapidly. For example, the 2016 average wage-adjusted price for a vaginal delivery was twice as high in Rating Area 9 (which has Monterey as its largest county) as it was in Rating Area 19 (San Diego) — $22,751 versus $11,387. (See next figure.) Prices for the service are increasing rapidly across counties — rising anywhere from 29% in San Francisco from 2012 to 2016 to 40% in Orange County over the same period.

The authors of the CHCF report investigated the impact of various types of consolidation on the prices of individual medical services in California. For cesarean births without complications, a 10% rise in hospital HHI is associated with a 1.3% increase in price.

Potential Policy Responses to Consolidation

While the study shows significant associations between various types of market concentration and the prices consumers pay, policymakers should carefully consider implementing steps that restrain the inflationary impact of consolidation while allowing the benefits of clinical integration to proliferate. To that end, the authors of the CHCF report offered a series of recommendations, which include:

Enforce antitrust laws. Federal and state governments should scrutinize proposed mergers and acquisitions to evaluate whether the net result is procompetitive or anticompetitive.

Restrict anticompetitive behaviors. Anticompetitive behaviors, such as all-or-nothing and anti-incentive contract terms, should be addressed through legislation or the courts in markets where providers are highly concentrated.

Revise anticompetitive reimbursement incentives. Reimbursement policies that reduce competition, such as Medicare rules that implicitly reward hospital-owned physician groups, should be adjusted.

Reduce barriers to market entry. Policies that restrict who can participate in the health care market, such as laws prohibiting nurse practitioners from practicing independently from a physician, should be changed when markets are concentrated.

Regulate provider and insurer rates. If antitrust enforcement is not successful and significant barriers to market entry exist — including those in small markets unable to support a competitive number of hospitals and specialists — regulating provider and insurer rates should be considered.

Encouraging meaningful competition in health care markets is an exceedingly difficult task for policymakers. It is no easier to promote the benefits of clinical integration while restraining the inflationary aspects of economic consolidation through public policy. Despite these challenges, the rapid rise in health care premiums and prices in the state require a fresh look at the consequences of widespread horizontal and vertical consolidation in California.

Authors & Contributors