While many health care organizations recognize the urgency of addressing inequities in health, efforts to do so are often slow, incremental, or incomplete. The health care system at large struggles to meaningfully incorporate and center “end users” of services (such as patients, administrative staff, and others who participate in the health care system regularly) in the feedback and co-design processes.

At the March 2023 convening for the California Improvement Network (CIN), Dr. Stella Safo, an HIV primary care physician and founder of Just Equity for Health (JEH), highlighted the foundational need for co-creation between health systems and community-based groups to address the social drivers of health and bring about meaningful structural change. CIN, a network run by Healthforce Center at UCSF and funded by the California Health Care Foundation (CHCF), brings together health care and community-based organizations to strengthen relationships and build collaborations to improve equitable health.

Safo offered reasons for why such collaborations often fall short, such as insufficient resources, limited expertise in incorporating community voices in health care design, and the fear of failure. Through her years of professional and lived experience, Safo highlighted the importance of bi-directional communication in the health care system and urged health care organizations to employ a systems-thinking approach to ensure that the voices of those most impacted are heard, centered, and addressed.

Even when organizations have the best intentions to incorporate community voices, they may not be successful if the conditions for co-creation are insufficient. For example, not adequately compensating community members for their time and input, setting meetings during work hours, or requiring people to travel to the health centers, may mean that only those who have the ability and resources to participate are heard from.

A lack of knowledge on how to be intentional in these efforts is another challenge and one that can lead to a fear of failing or limited actions due to worry about any legal ramifications. It is imperative that these realities are considered and acknowledged to maximize community voices in co-design efforts and create health systems that are responsive and community centered.

“It’s often the fear of starting from nothing at all that prevents people from wanting to do this kind of equity-based redesign work.”

— Dr. Stella Safo

So how does the health care system begin to overcome these challenges and strive for meaningful change? Safo offers three main interventions that her organization employs:

- Let communities lead.

- Create multiple points of accountability.

- Develop a customized equity framework.

Let Communities Lead

Safo urges resistance against the all-too-common impulse for health care organizations to dominate co-design and collaboration opportunities. Supporting and enabling community members to lead this work requires health care leaders to think about the intersectional roles they hold. For example, convening a community advisory board to solicit feedback may not always be feasible, but health care organizations can evaluate their existing patient population to determine the other positions they may hold within the community and how those relationships can lead to more meaningful and responsive partnerships. Additionally, organizations must adapt and create realistic timelines and budgets that support productive collaborations with adequate time to partner with communities, meaningfully codesign, and compensate community members’ time, effort, and expertise.

Safo and her team at Just Equity for Health successfully deployed these strategies while supporting a community-driven partnership to increase COVID-19 vaccination rates. Community groups expressed a need for a trusted messenger campaign (where health care professionals went out into the community to spread the word and dispelled misinformation about the COVID-19 vaccine). Instead of JEH determining the messaging and mode of relaying this message, the community groups determined what to say and where. Meeting community members at the spaces they already frequent and trust meant that the messaging was more likely to resonate.

Impactful co-design requires organizations to be accountable for their commitments to meet the health and social needs of communities.

Create Multiple Points of Accountability

Impactful co-design requires organizations to be accountable for their commitments to meet the health and social needs of communities. This means seeking feedback, measuring progress, and sharing that data back with communities. This is essential for building trust between communities and health systems, and it allows for more points of collaboration and improvement for all parties. When people in the community feel that their input is actually being heard, they are more likely to participate in future endeavors.

Community-based organizations build power through partnerships with local political entities, such as city council and in doing so, increase the likelihood that health systems will follow through on their commitments to the community. As political entities typically hold more power than community groups, they raise the weight of accountability on health systems.

Create a Customized Equity Framework

Finally, housing this work within a reparative equity framework and customizing it according to the needs and priorities of communities is key for successful co-design. Health equity frameworks guide users in defining the set of social drivers impacting the health outcomes for their communities and identifying the actions and strategies that organizations can implement to systematically address inequities and creating a plan to do this work in partnership with end users. These frameworks should be customized to the health system and local context and must be easy to use across the health care ecosystem.

When selecting a framework, some questions to consider are:

- What are the key tenets that can be brought forward that matters the most to the people being served?

- How will buy-in from executives as well as from those that are going to be using this framework most often (that is, frontline staff and patients) be attained?

- How will the impact of implementing the framework be measured?

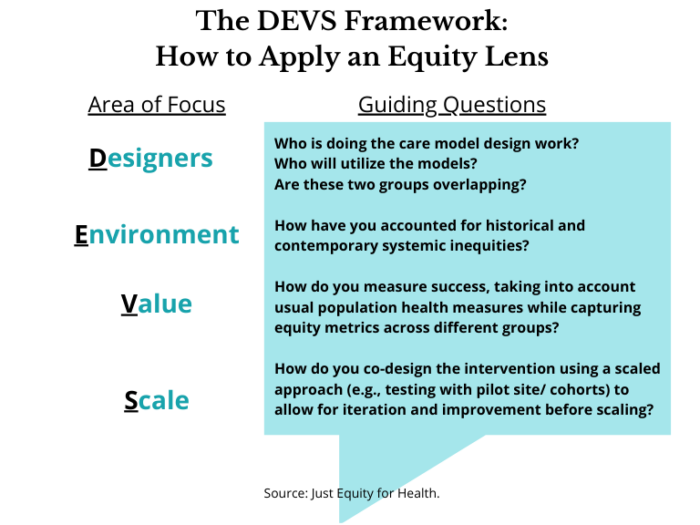

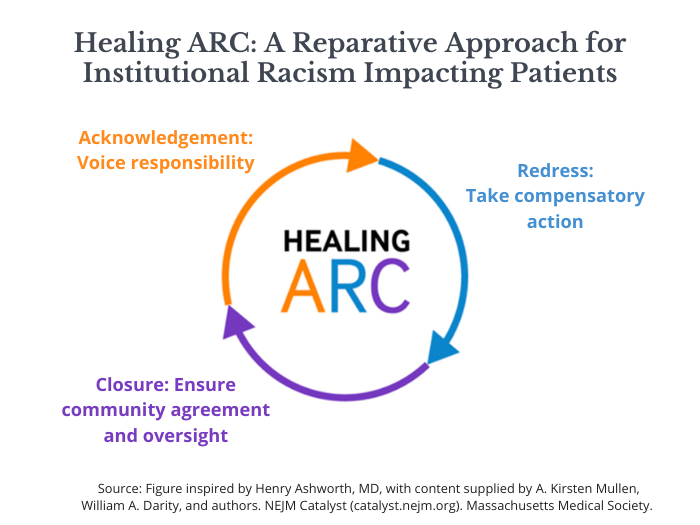

Safo offered two frameworks as a starting point for any organization that is ready to commit to beginning this work: the DEVS Framework (Designers, Environment, Value, Scale) and the Healing ARC Framework.

The DEVS Framework, created by Safo and her team at JEH, offers a guide on how to apply an equity lens to the work. The areas of focus (Designers, Environment, Value and Scale) represent the breadth of players in co-design work, the context under which this work is being done, how to measure the value of this work across different groups, and how to scale interventions systematically.

The Healing ARC Framework, developed by Drs. Bram Wispelwey and Michelle Morse, uses a reparative justice lens to help institutions consider how to reimagine patient care in a way that is rooted in social justice. The framework works by acknowledging the historic and institutional harm, elevating those most impacted by this history, and designing solutions that center their voices. Through an iterative process, organizations continue to adapt interventions based on feedback. Finally, organizations close the loop by ensuring community agreement on the value and impact of an intervention.

A key example of how the Healing ARC Framework has been applied is through the work of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, MA. Drs. Morse and Wispelwey found that historically, Black and Hispanic patients who were admitted to the emergency department for heart failure were not being referred to specialty cardiac care services at the same rates as other racial and ethnic groups. Using the Healing ARC Framework, Morse and Wispelwey designed a patient care delivery model to prioritize Black and Hispanic patients and improve connectedness to care and patient outcomes.

“Medicine should be viewed as social justice work in a world that is so sick and so riven by inequities.”

— Dr. Paul Farmer

Transforming systems is not easy, especially at a time when health care entities are overworked and understaffed. In many ways, it might feel impossible to move the needle forward, but in moments like these, it is important to center the “why” for this work. At the core, health care systems are responsible for their patients and their communities. In her closing, Stella Safo asserted that to strive for more equitable communities, health care work is social justice work. It is time for health systems to embrace this call to view their work within the lens of social justice and advocate for the communities they serve.

Learn more about the California Improvement Network, a project of the California Health Care Foundation that is managed by Healthforce Center at UCSF, and sign up for the CIN newsletter.