Opioids killed an estimated 49,000 Americans in 2017, including nearly 2,200 Californians. They harmed many more, including children forced into the foster care system, babies born with neonatal abstinence syndrome, young adults who overdosed from dangerous new street drugs like fentanyl, and countless others who became addicted to opioids while trying to manage chronic pain.

In early October, Congress overwhelmingly passed bipartisan opioid legislation, including more than $3.3 billion in authorized spending over 10 years. The Senate approved the Substance Use Disorder Prevention that Promotes Opioid Recovery and Treatment for Patients and Communities Act, also known as the SUPPORT for Patients and Communities Act (HR 6), by a vote of 98-1, while the House approved it 396-14. President Trump signed the 660-page bill into law on October 24, 2018.

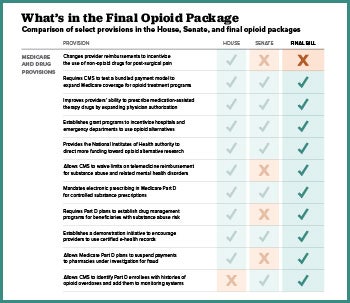

The legislation is an amalgamation of more than 70 bills introduced by Republicans and Democrats. The package aims to ease the epidemic by increasing access to effective treatment within Medicaid and Medicare, expanding alternative non-opioid pain management options, reducing over-prescribing, educating patients, identifying best practices that can effectively address the epidemic in the future, and more. Here are some of the key components.

Expanding Access to Recovery Drugs and Treatment

Increasing the Availability of Therapy and Medication-Assisted Treatment

HR 6 expands the type of health care providers who can prescribe or dispense medication-assisted treatment (MAT), as well as the number of patients each provider is allowed to treat. The bill grants physician assistants and nurse practitioners permanent authority to prescribe MAT, and authorizes, for a five-year period, nurse specialists, nurse midwives, and nurse anesthetists to prescribe MAT. Expanding who can prescribe MAT is the second largest projected expenditure in the bill — $395 million over 10 years. This includes grants for Federally Qualified Health Centers and rural health clinics to cover the cost of training providers in the use of the medications to treat opioid use disorders.

The law also expands access to treatment by paying opioid treatment programs, which historically have not been eligible for Medicare reimbursement, a bundled MAT payment for medication, counseling, and treatment. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects this will cost $250 million over the next decade.

The bill’s largest expenditure allows states to use their Medicaid program for a five-year period to cover care in institutions for mental diseases (IMD). This “IMD exclusion” had prohibited Medicaid from reimbursing for residential or inpatient care at facilities with more than 16 beds. Over the five years that states can use this option, the CBO estimates it will cost $1 billion. This provision generated intense debate. Some lawmakers wanted broader repeal of the Medicaid IMD exclusion, while others registered fiscal objections or expressed concern about the risk that it would turn back the clock toward the use of institutionalization rather than community-based care.

Mental and behavioral health providers participating in the National Health Service Corps will be allowed to provide care at school and community-based settings in shortage areas. The bill authorizes $10 million in annual grants from 2019 to 2023 to support comprehensive opioid recovery centers, which offer treatment services, including drugs, devices, counseling, peer support, and housing. It’s important to note that, as with most of the legislation’s fiscal provisions, the bill authorizes Congress to appropriate the funds. Appropriation will take another act of Congress.

The bill authorizes $25 million a year from 2019 through 2023 to fund loan repayment agreements with substance use disorder (SUD) professionals in mental health professional shortage areas or in areas most affected by the epidemic. When funded, this will help expand the number of available providers.

Broadening Medicaid Eligibility for Former Foster Care Youth

States will be required to ensure that former foster children continue to have Medicaid coverage across state lines until the age of 26 — a provision sought by children’s hospitals and other stakeholders. This ensures health coverage for vulnerable patients and a payer source for the clinical systems that serve them. It is not uncommon for children’s hospitals and other health care systems to serve patients across regions, including multiple states. This provision will give young adults reliable access to addiction treatment as well as to services upstream to prevent addiction in the first place or catch it in its early phases.

Extending Reimbursement

Requiring Medicaid Coverage of MAT

The bill requires states’ Medicaid programs to cover MAT, including drugs, biological products, counseling services, and behavioral therapy, unless it is not feasible to do so due to a shortage of qualified providers or treatment facilities. The requirement applies for five years. In California, Medi-Cal currently covers MAT both through the county-administered Drug Medi-Cal system (including the Organized Delivery System operating in 19 counties) and through Medi-Cal fee-for-service.

Advancing Telehealth in Public Programs

Medicare beneficiaries with substance use and mental health disorders will have expanded access to treatment via telehealth technology. Providers will be eligible for Medicare reimbursement even when services are provided within a beneficiary’s home, something that is currently difficult. Within a year, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) is required to issue guidance to states on how federal reimbursement can fund telehealth services within Medicaid, including school-based services and services for high-risk individuals, such as Native Americans, adults under 40, people with a history of overdose, and individuals experiencing a serious mental illness along with an SUD. Federal reimbursement will be allowed for telehealth services including assessment, MAT, counseling, medication management, and medication adherence.

Behavioral health providers, such as select community mental health centers, hospitals, nurse practitioners, and clinical social workers, will be eligible for a Medicare incentive payment if they adopt certified electronic health records technology.

Investing in Pilot Programs and Delivery Reform

Strengthening and Expanding Medicaid and Medicare Coverage

HR 6 appropriates $50 million for CMS to support state Medicaid demonstration projects to increase patient access to SUD services by increasing the treatment capacity of Medicaid providers. The funding will support 18-month planning grants in at least 10 states and enhance federal Medicaid matching rates for five states. Approaches include provider education and training, as well as increased reimbursement for and expansion of relevant services. The demonstration projects will serve a range of Medicaid enrollees, including infants with neonatal abstinence syndrome, pregnant and postpartum women, adolescents, young adults, and Native Americans.

The bill creates a four-year demonstration program within Medicare to increase access to comprehensive, evidence-based outpatient treatment for some Medicare beneficiaries, including medication, psychosocial supports, care management, and treatment planning. The program will cost $107 million over a 10-year period, and care will be provided by opioid use disorder teams with at least one physician or other prescriber plus optional providers offering psychological, counseling, and/or social services. The program will also include incentive payments based on performance.

Extending Medicaid Health Homes

Federal funding will be extended for Medicaid health home programs that primarily serve individuals diagnosed with an SUD along with a chronic disease. For states like California that already have a health homes program and thus already have an SUD-focused State Plan Amendment (SPA) in place, the bill extends funding for two extra quarters. The bill would allow other states to add the program (via an SUD-focused SPA) and to receive enhanced federal funding for two and a half years.

Ensuring Safe Medications

Ensuring Safe Access to Medications; Curbing the Importation of Illicit Drugs

Medicare providers are required to use e-prescribing for opioids, and Medicare prescription drug plans are required to establish drug management programs for at-risk enrollees. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) can now require drug manufacturers to alter opioid packaging so doctors can prescribe smaller quantities, such as a three- or seven-day supply, rather than the traditional 30-day supply. The FDA can now also require manufacturers to give patients safe options for disposing of medications, such as charcoal bags that can be used to destroy unneeded medications at home, thus reducing the risk of medications being misused later.

Other provisions are designed to combat importation of illicit drugs like fentanyl, a powerful synthetic opioid that has caused many deaths. Because fentanyl is concentrated, it can readily be mailed undetected into the US. The law strengthens coordination between the FDA and US Customs and Border Protection to improve detection and testing equipment and to enhance package inspection capacity. It also requires the FDA to develop and update a list of controlled substances to refer to the customs agency for screening of international mail.

Alternative Treatments

Expanding Access to Alternative Pain Treatments

The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) is required to issue guidance on state Medicaid options for non-opioid treatments, and the bill clarifies how non-addictive medical products qualify for FDA expedited review. Funding for demonstration programs to test alternate pain management protocols in emergency departments is also authorized by the bill.

Educational Initiatives

Advancing Public Health Screening and Prevention

Screening for SUDs will be added to Medicare wellness and preventive care visits to expand early detection and timely treatment. This is relatively inexpensive, but it is key to shifting activities toward prevention and early intervention.

Provider and Community Education

Medicare patients will receive annual educational information about the opioid use, pain management, and non-opioid treatment options available. This will include information from Medicare Advantage plans regarding the risks associated with prolonged opioid use, and Medicare coverage of nonpharmacological therapies, devices, and non-opioid medications. Educational resources for providers will include a toolkit with best practices for hospitals in reducing opioid use. Medicare Advantage and prescription drug plans will be required to provide information regarding the safe disposal of prescription drugs. Clinicians will receive educational materials encouraging pregnant women to participate in decisions regarding pain management before and after childbirth. Outreach and education grants totaling $75 million will help outlier prescribers reduce opioid prescribing.

Public Health and Research

Addressing Social Determinants of Health

HHS will provide technical assistance to states that develop housing-related supports and care coordination services for SUD patients in Medicaid. The department will share information on successful, innovative housing-related services to help individuals with SUD avoid becoming homeless.

Impacts on Women and Children

The law increases access to prevention and treatment for women and children and on reunifying families broken apart by addiction. It allocates $15 million to replicate a program that helps parents reunify with children placed in foster care. An additional $20 million is authorized to help states develop, enhance, or evaluate family-focused treatment programs, and HHS will help states identify opportunities to support these programs with help from federal matching funds. The bill reauthorizes the Residential Treatment for Pregnant and Postpartum Women grant program, which has historically funded efforts in four areas of California. The Government Accountability Office will study gaps in Medicaid coverage for pregnant and postpartum women with SUDs.

Conclusion: More Is Needed

This bill represents a positive step towards curbing the opioid epidemic. It is, however, an incremental step rather than a silver bullet, and critics argue that it falls significantly short of what is needed to solve a crisis of this magnitude. Many called for sustained, robust funding like the Ryan White HIV/AIDS program enacted to combat an epidemic of similar size, and this bill is far from that.

Authors & Contributors

Billy Wynne

Billy Wynne is founder and CEO of the Wynne Health Group, a Washington-based consulting and advocacy practice serving clients throughout the health care sector. A graduate of Dartmouth College and the University of Virginia School of Law, Billy previously served as health policy counsel to the US Senate Finance Committee.

Dawn Joyce

Dawn Joyce is a vice president with the Wynne Health Group and a health policy expert. She has hands-on experience at the federal, state, and local levels, and previously served as a staff member for California senator Dianne Feinstein.

Joyce is a graduate of Wellesley College and UC Berkeley’s School of Public Health.