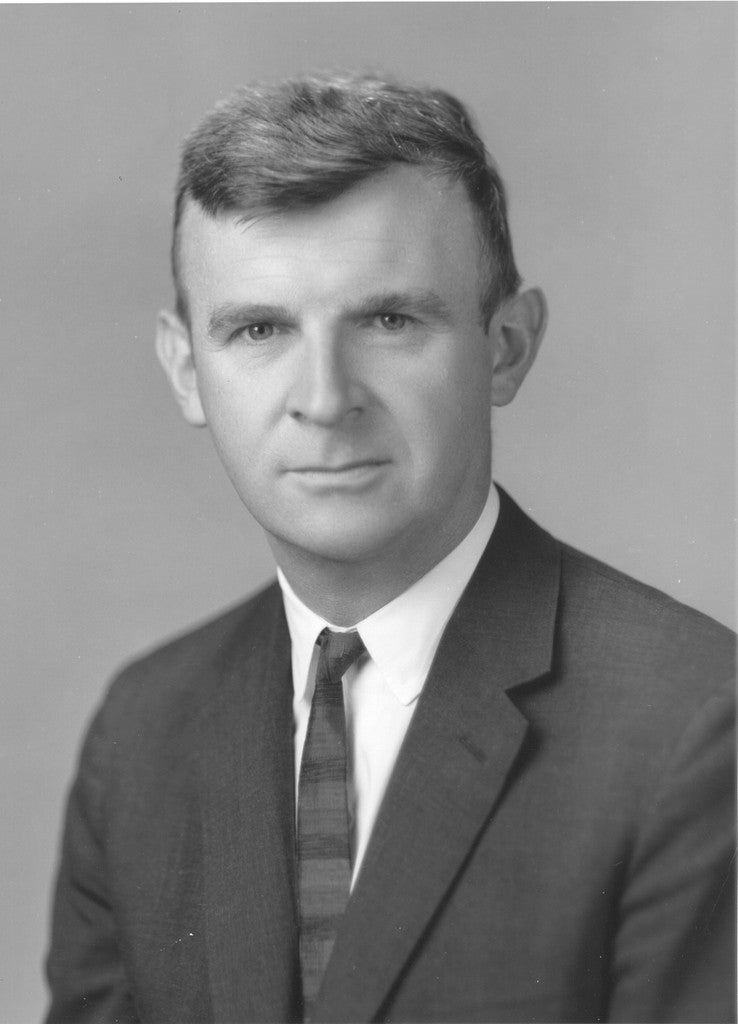

Philip R. Lee, MD, a California health policy leader who mentored future physician leaders and served as one of the architects of the Medicare program, died in New York City on October 27, 2020. He was 96.

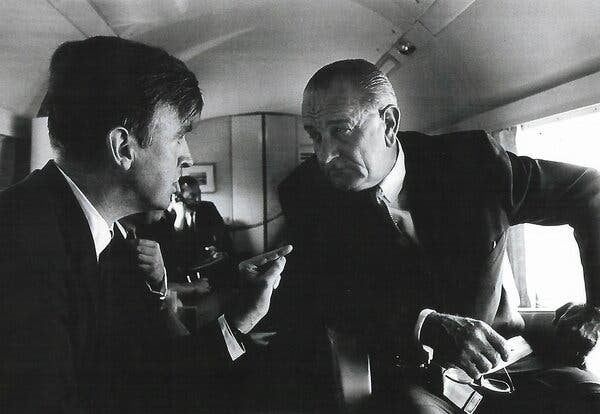

As assistant secretary for health in the administration of President Lyndon Johnson, Dr. Lee oversaw the implementation of Medicare and used the program as a powerful tool to combat racial segregation then prevalent in hospitals. When Congress passed the Social Security Act amendments that created Medicare and Medicaid in 1965, thousands of American hospitals had a standard practice of segregating patients based on race. Dr. Lee pushed the administration to bar federal funding for hospitals that refused to integrate.

When the law took effect in 1966, Dr. Lee was sent to the South to ensure hospitals met the desegregation requirements, which applied to patients, staff, and the collection and allocation of the blood supply. Within a year, 95% of the nation’s hospitals were deemed to be in compliance.

“To Phil, Medicare wasn’t just a ‘big law’ expanding coverage — it was a vehicle to address racial and economic injustice,” said Peter Lee, Dr. Lee’s nephew and executive director of Covered California, in a tribute published by the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF). “The importance of racial equity, health equity, and addressing the social determinants of health are values that Phil embedded in me and in all the people he influenced as a teacher.”

As a champion of Medicare, Dr. Lee drew attacks from opponents of the program — including Ronald Reagan, who went on to become governor of California and president of the United States.

Medicare plays a key role in providing health coverage and financial stability to Americans over 65 as well as to younger people with certain disabilities. In 2019, enrollment stood at 64 million, and it remains one of the nation’s most important and popular government-run programs. Each day, 10,000 Americans reach their 65th birthday and are required to register with the program.

A Medical Family

Philip Randolph Lee was born at Stanford Hospital on April 17, 1924, to Russel Van Arsdale Lee, MD, founder of the Palo Alto Medical Clinic, now known as the Palo Alto Medical Foundation, and Dorothy Lee, an amateur musician. Phil Lee earned his undergraduate and medical degrees from Stanford University before serving in the US Navy during the Korean War. He completed fellowships in physical medicine and rehabilitation at New York University and the Mayo Clinic, and he earned a master of science degree from the University of Minnesota.

Before joining the Johnson administration, Dr. Lee served as director of health for the State Department’s Agency for International Development, guiding efforts to improve nutrition, eradicate malaria, and provide international family planning services.

After the Johnson administration ended, Dr. Lee returned to San Francisco to serve as chancellor of UCSF from 1969 to 1972. He worked closely with the UCSF Black Caucus, a group of employees, to bring about more equitable employment practices and greater racial diversity across the university. At the same time, Dr. Lee envisioned a multidisciplinary research program that would address racial and ethnic disparities in access to care and quality of care, reduce health costs, and bridge gaps in the health care workforce. After the chancellorship, he established UCSF’s Health Policy Program, which he led until 1993 and developed into the Institute for Health Policy Studies (IHPS).

“The institute he founded became the model for the health policy institutes across the country,” Claire Brindis, DrPH, former director of the IHPS, said in the UCSF article. “The scaffolding he laid with his ideas endures in all the work of the IHPS today.”

In 2007, UCSF honored Dr. Lee by rebranding IHPS as the Philip R. Lee Institute for Health Policy Studies.

“To all of us who came under Phil’s spell, his death represents the end of an era,” said former UCSF Chancellor Haile Debas, MD, in the UCSF tribute. “He was a giant of a leader, a man with passionate commitment to the welfare of the poor and vulnerable, and one who has made important contributions to the national discourse and direction of health policy. I will always remember Phil as the gentle giant who always had time and a smile for everyone and a burning passion to make this world a better place.”

After the election of President Bill Clinton in 1992, Dr. Lee was called back to public service. He again served as assistant secretary for health, from 1993 to 1998. He advised the administration on its attempt to enact a health care reform plan. While that plan was ultimately defeated, the experience served as important preparation for passage of the Affordable Care Act during the administration of President Barack Obama in 2010.

HIV/AIDS Crisis in San Francisco

During Dr. Lee’s health policy tenure at UCSF, the HIV/AIDS crisis erupted. He guided the hard-hit city of San Francisco through the epidemic as the first president of the Health Commission of the City and County of San Francisco. He was appointed by then San Francisco mayor Dianne Feinstein.

“Phil was a mentor to me,” said CHCF president and CEO Sandra R. Hernández, MD. “In the mid-1980s I was a UCSF medical resident and he was chairing the Health Commission. A hospital patient of mine needed regular hemodialysis, and I was upset about the city’s antiquated policy limiting undocumented patients’ access to that care. Phil challenged me to back up my request for a policy change with good data. I did, and he made the policy change happen. I’ll never forget that because it was my first effort at health policy reform.”

Harold S. Luft, PhD, the second director of IHPS, remembered his predecessor as a nimble thinker. “Phil demonstrated, in small ways and large, how to pivot to meet needs,” Luft said in the UCSF article. Initially, the work of IHPS focused on Washington, but it adapted to external events and shifted when the next health policy priority arose. “When HIV/AIDS hit San Francisco, when health reform came back on the agenda, and when pharmaceuticals would be covered under Medicare, the program Phil built had answers ready to be used,” Luft said.

Among Dr. Lee’s numerous and diverse contributions to health policy at the state and national level, there was one variable that remained constant: his wholehearted dedication to health care justice.

“Phil was an icon in the health policy world,” said Hernández. “Millions of Americans owe him a debt of gratitude for making our lives better and longer.”

Dr. Lee is survived by his wife, Roz Lasker, MD, and five children from his first marriage, Dorothy, Paul, Margaret, Theodore Lee, and Amy Lee Pinneo; a stepdaughter, Duskie Estes; seven grandchildren; and two great-grandchildren.

IHPS and UCSF plan to announce a celebration of Dr. Lee’s life.

Authors & Contributors