|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready…

|

Jessie Qualls Jr. wasn’t sure he could trust the therapist sitting in front of him at the San Ysidro Health clinic in San Ysidro, a community in the city of San Diego along the border with Mexico.

The 46-year-old from nearby Chula Vista had never seen a mental health professional before, and the idea of revealing his personal struggles to a stranger felt daunting. But his primary care doctor, whom he did trust, had referred Qualls to the clinic. Both providers worked for San Ysidro Health, a Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC) with sites throughout San Diego County. And Qualls knew he needed help.

“I was in a rough spot: down, depressed, couldn’t sleep, didn’t eat very much,” said Qualls, who at the time of his first appointment in 2021 had fallen into a severe depression after losing his job at Walmart and finding out he had a heart problem. “It felt like I was failing at paying rent and supporting my girlfriend at the time, and my daughter. I was in a bad place,” he said.

Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinics

Qualls didn’t realize it, but he was among the first patients to receive services under a San Ysidro Health program that’s reimagining mental health and substance use disorder treatment. The program is part of a federal effort to find ways to make behavioral health care — an umbrella term that encompasses treatment for both mental illness and substance use disorder — more accessible, coordinated, and effective for people who are eligible for Medi-Cal, California’s Medicaid program.

Called certified community behavioral health clinics, or CCBHCs, these programs are a departure from California’s traditional behavioral health treatment model, which pushes patients into different systems based on the type and severity of their conditions. Under the typical Medi-Cal model, patients with mild to moderate mental illness are entitled to get treatment through their Medi-Cal managed care plan — sometimes where they receive primary care or at an affiliated clinic, but often through referral to an outside mental health provider. People with more serious mental illness who need specialized services are typically referred to their county mental health department for treatment. Counties also provide substance use disorder treatment, but often separately from their mental health programs.

CCBHCs streamline care for patients with behavioral and physical health needs. They have proliferated across the country since the federal government first authorized them in 2014. Yet so far, California has only 22 CCBHCs, including the one run by San Ysidro Health. A primary reason for this relatively small number is that California, unlike many other states, does not have a statewide program to support these clinics.

San Ysidro Health’s CCBHC is located less than three miles north of the nearest border crossing and has a view of Tijuana, Mexico. The clinic serves a wide array of patients, including native San Diegans; recent immigrants; dual nationals; refugees and asylum seekers; people from the LGBTQ+ community; patients who are pregnant or recently gave birth; and people like Qualls who have multiple medical conditions. More than half of the patients are Latino/x.

Many have experienced trauma, including childhood sexual abuse, human trafficking, domestic violence, gang violence, war, natural disasters, suicide, and extreme poverty. The clinic receives about 74 patient referrals each month, usually from San Ysidro Health primary care physicians and local hospitals, and has a total of 500 to 600 patients actively engaged in treatment at any given time. That’s around 6% of all patients referred for behavioral health care within the San Ysidro Health system, according to its chief behavioral health officer, Gaurav Mishra, MD, MBA.

Coordination of Services

San Ysidro Health, in line with the CCBHC model, treats patients across the spectrum of mental health and substance use disorders within its community clinic system, and it offers integrated mental health and substance use treatment simultaneously to those who need it. Patients with mild to moderate conditions receive the less intensive treatment typically available through Medi-Cal managed care plans and FQHCs. These services are provided at San Ysidro Health’s primary care and behavioral health clinics and may include supportive counseling, medications, therapy, psychiatry, and case management. Patients with more serious illnesses and complex needs are referred to San Ysidro Health’s CCBHC, which is located with one of the organization’s senior health centers, an on-site lab, and a pediatric behavioral health program. Some CCBHC services are also offered at other San Ysidro Health clinics.

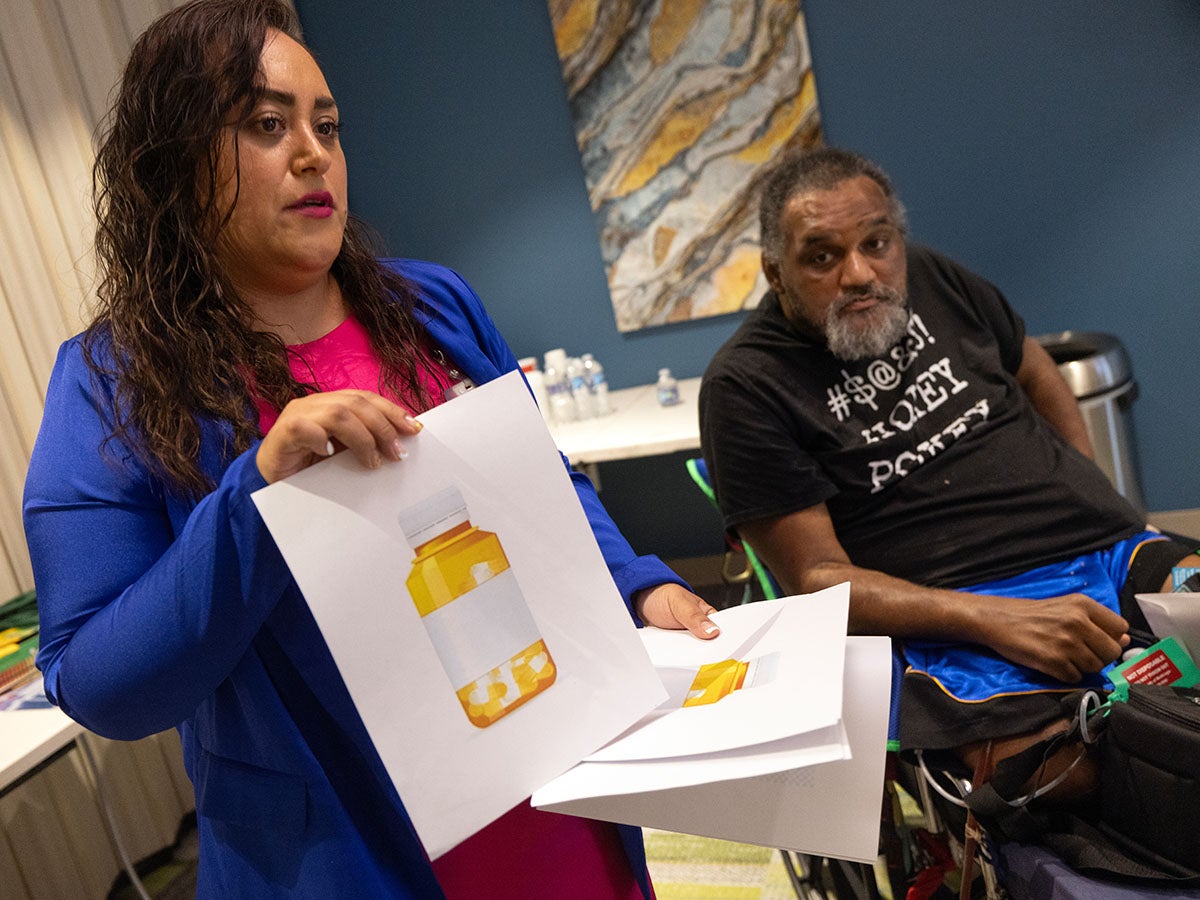

Patients enrolled at San Ysidro Health’s CCBHC meet at least once a week with a therapist and monthly or more frequently with a psychiatrist, depending on their level of need. They also see an on-site case manager on a weekly basis who helps coordinate their care; organize transportation; and connect them with other services and resources, such as food, financial help, and housing. Patients have access to an on-site nurse and individual peer support, and they can attend educational group classes in English, Spanish, and Arabic. Recently, the clinic added a food pantry, a diaper bank, and behavioral health services for people who are or intend to become pregnant.

Salvador Lynn, 48, an immigrant from Mexico who now lives in Chula Vista, said he much prefers the care he receives at the San Ysidro clinic to his prior experience at another behavioral health program 10 miles away. In the past, he saw a psychiatrist just once a month for his schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, and he had to travel 40 minutes by bus and foot to get there before waiting for over an hour in a crowded waiting room. Now that he sees a therapist and psychiatrist weekly, Lynn has been able to work through childhood traumas, including the suicide of his father; develop better coping skills; and improve his eating and exercise habits. He also attends group wellness classes.

“It’s healthier,” he said of the San Ysidro Health model. “It’s way better. You can take care of business more.”

The advantage of treating all patients within the same organization regardless of the severity of their conditions is that it’s much easier to coordinate treatment. It also helps facilitate the transitioning of patients to higher or lower levels of care without losing them in the referral process, said Mishra, who oversees the clinic.

Patients find the care easier to navigate because they’re usually already receiving primary care through San Ysidro Health and are familiar with the center. What’s more, because all the providers — including mental and physical health clinicians — are part of San Ysidro Health, they share the same electronic health records system and can easily communicate with each other about their patients in order to coordinate treatment.

That seamless communication has been vital for Qualls, who also receives care through San Ysidro Health for diabetes and heart disease, conditions that have necessitated the amputation of both legs. It is straightforward for his psychiatrist at the CCBHC to consult with his primary care doctor to make sure the medications he’s taking don’t interact poorly. His psychiatrist also consults with his therapist to ensure they’re aligning over his mental health treatment. Meanwhile, Qualls’ case manager, Laura Gomez-Cancino, organizes transportation to his appointments from the nursing home where he lives and helped him get Medi-Cal after he lost the private health insurance Walmart had provided.

This scenario is light-years away from what psychiatrist Priti Ojha, MD, remembers experiencing when she worked for a mental health program that contracted with the county. There, if she wanted to communicate with a patient’s primary care doctor, she had to call and leave a message. Usually, they never called back or, if they did respond, it was to refuse to provide information due to a misunderstanding of patient privacy rules.

“It was incredibly frustrating because my hands are tied, and I can’t really provide that whole-person-centered care,” said Ojha, who is now the medical director of San Ysidro Health’s CCBHC. “Here, I feel like we really are able to make an impact, and patients really appreciate when I say, ‘Well, let me just send your primary care doc a quick message to give them a heads up about this.’”

Ojha said she also received less case management support in her previous job. Some behavioral health clinicians at San Ysidro Health said that prior to working at the CCBHC, they had no case manager to support them, which meant they had to spend valuable appointment time doing case management work themselves.

The clinic’s ability to integrate behavioral and physical health care and provide comprehensive case management results in better care for patients, Mishra said. It also created a more satisfying work environment for clinical staff that has improved retention and hiring, he added. Before leading the launch of San Ysidro Health’s CCBHC in 2020, he regularly encountered seriously mentally ill patients who had been referred to county behavioral health services a year prior but never received treatment beyond getting prescriptions filled. Meanwhile, mental health clinicians working at San Ysidro Health and those who worked elsewhere before joining the CCBHC frequently burned out because they felt they didn’t have the necessary tools to help seriously ill patients, he said.

Dr. Luke Bergmann, director of San Diego County’s Behavioral Health Services Department, said patients referred to the county do receive comprehensive support. Patients enter the county system because they are experiencing a behavioral health crisis and will go to the county’s psychiatric hospital, one of its six crisis stabilization units, or to beds at local hospitals that the county pays for.

Patients at county-run facilities receive care coordination for a month after discharge to connect them to community behavioral health services. However, it’s difficult for the county to track what happens to patients after they’re released from non-county hospitals, Bergmann said, because these facilities have different electronic health records systems. It’s possible that contact is lost even with patients discharged from county facilities, and those patients don’t end up receiving the follow-up care they need, he said.

A big obstacle to coordinating care is the lack of an integrated health care data infrastructure that would allow providers to share information across systems, Bergman said. There’s also a need for incentives to strengthen the provision of mild-to-moderate behavioral health care so patients don’t reach the level of needing county intervention, he said. The current arrangement of having counties take financial responsibility for people once they have a behavioral health crisis discourages insurers from investing in lower-acuity care, he said.

Bergman supports the CCBHC model but doesn’t think it solves all the system’s problems, particularly because it doesn’t encompass inpatient, crisis-level care. The benefit of having a CCBHC within an FQHC like San Ysidro Health is that it enables integration of behavioral and physical medical care, he said.

“I think CCBHCs reflect a sensibility that’s foundational to improving the system, which is that behavioral health care is health care, and behavioral health care should be integrated with other kinds of health care,” Bergman said.

CCBHC Grant Funding

In California, CCBHCs operate with grant funding from the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) that covers startup and expansion costs for up to four years at a time. San Ysidro Health’s CCBHC has received two such grants, with the latest set to expire in 2026. Because it’s in an FQHC, the clinic gets some reimbursement through Medi-Cal, but those payments don’t cover the full range of services like case management, peer support, substance use counseling, group therapy, and nursing.

The looming federal grant expiration date worries Mishra even as the program enjoys success in patient outcomes and satisfaction levels. Demand for services outpaces clinic capacity, he said. CCBHCs have been shown to reduce homelessness, substance use, emergency room visits, and hospitalizations, according to SAMHSA.

To ensure long-term sustainability for CCBHCs and facilitate their spread throughout the state, California could apply to the federal government to become a CCBHC demonstration program state. That would allow clinics in California to receive Medicaid payments to cover all CCBHC services on an ongoing basis, rather than relying on one-time grant funds. Eighteen states have joined the program, beginning with 8 after a first round of applications in 2016 and another 10 following a second round in June 2024.

California applied to the program in 2016 but was not accepted. The next opportunity for the state to apply is in 2026.

A Needed Solution

“The existing system is not serving the patients effectively, so we definitely need this solution,” Mishra said. “We could easily set up 10 more CCBHC programs in San Diego County, and they would be full within a year.”

Meanwhile, Mishra said he draws strength and inspiration from the participants he met through the CHCF Health Care Leadership Program, a two-year, part-time fellowship for clinically trained health care professionals. The fellowship showed him the many determined health care leaders trying to find solutions to complex problems in the health care system, he said.

For Qualls, getting care through San Ysidro Health’s CCBHC has allowed him to find relief from his depression and brought him greater happiness and peace despite physical health challenges. His therapist and psychiatrist quickly gained his trust, he said, by talking to him as if he were a friend.

“I feel about 98% better,” he said. The treatment “made me realize you don’t always have good days. You have some bad days. You just have to try to have more good days than bad.”

Authors & Contributors

Claudia Boyd-Barrett

Claudia Boyd-Barrett is a longtime journalist based in Southern California. She writes regularly about health and social inequities. Her stories have appeared in the Los Angeles Times, San Francisco Chronicle, San Diego Union-Tribune, and California Health Report, among others.

Boyd-Barrett is a two-time USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism fellow and a former Inter American Press Association fellow.

Hayne Palmour IV

Hayne Palmour IV worked as a staff photographer for San Diego County newspapers for more than three decades, including eight years at the San Diego Union-Tribune. He covered news, features, and sports and continues working as a freelance photojournalist in Southern California.

In 2003, the North County Times published a book featuring Palmour’s photographs of the 2003 US invasion of Iraq titled A Thousand Miles to Baghdad.

He has an associate’s degree in photography from Chowan College in North Carolina and a BA in psychology from the University of North Carolina-Wilmington.