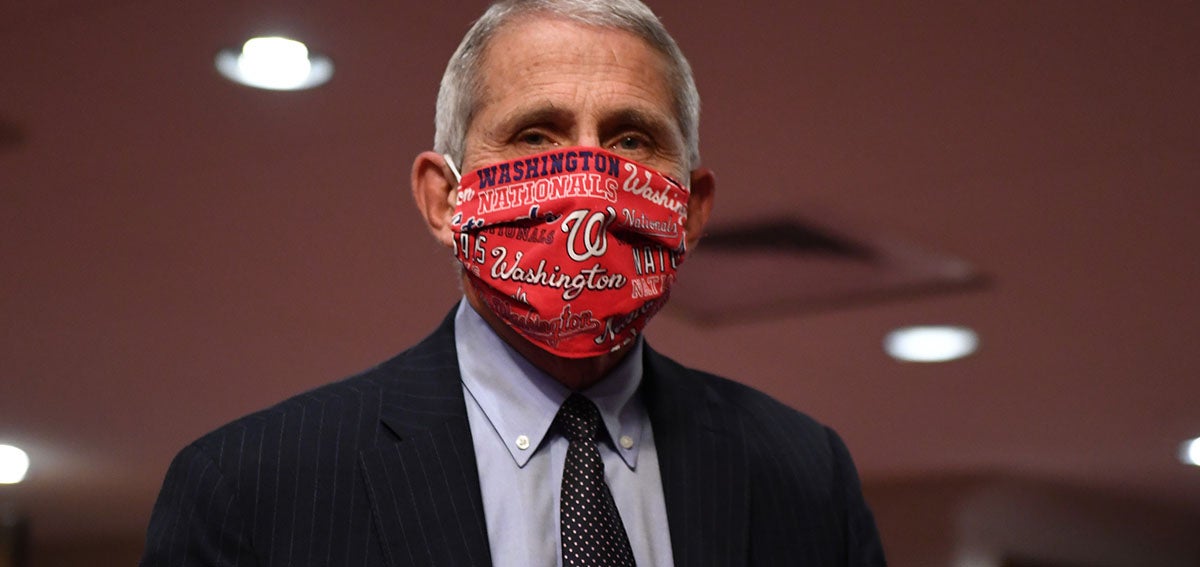

When the Trump administration began holding coronavirus press briefings at the White House in March, Anthony Fauci, MD, legendary longtime director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, again became a household name to millions of Americans grasping for reliable information about the pandemic. Fauci first gained national recognition in the 1980s when he led the National Institutes of Health response to the AIDS epidemic.

Even though — or perhaps because — Fauci has publicly refuted President Trump’s statements about COVID-19 and criticized some states for reopening too quickly, he is one of the most trusted federal officials on the topic. A recent New York Times / Siena College poll found that 67% of American voters trust Fauci for accurate information about the coronavirus, compared to the 26% who trust Trump.

But on July 11, the Washington Post reported that the relationship between Fauci and the White House had soured, and that Fauci had not spoken to the president since early June — even as COVID-19 cases soared nationwide. To discredit Fauci, a White House official provided the Post and other news outlets with “a lengthy list of the scientist’s comments from early in the outbreak” to suggest that Fauci has been wrong many times. Fauci made those errors when information about the coronavirus was limited, and he has always said that expert recommendations would change as scientists learned more about the new virus.

“The response at the highest office in the land [is to ignore] data, science, and facts. . . . That feeds into the local dynamics we’re seeing across the country.”

—Grant Colfax, MD, San Francisco Department of Public Health

Public health and medical experts leapt to Fauci’s defense. “Taking quotes from Dr. Fauci out of context to discredit his scientific knowledge and judgment will do tremendous harm to our nation’s efforts to get the virus under control, restore our economy, and return us to a more normal way of life,” Association of American Medical Colleges CEO David J. Skorton, MD, and Chief Scientific Officer Ross McKinney Jr., MD, said in a statement.

Fauci “has been steadfast in his commitment to improve and preserve the health and public health of this country using science and evidence as his guide,” Howard Bauchner, MD, editor-in-chief of the Journal of the American Medical Association, wrote in an open letter. “He deserves our deepest gratitude and support.”

The White House has since softened its criticism of Fauci, with the president saying to reporters on July 15, “I have a very good relationship with Anthony.” However, the Trump administration’s smear was representative of a troubling trend — the discrediting of public health officers who are coping with the greatest public health crisis in a century.

Experts say the White House’s efforts to sideline Fauci emboldened similar attacks on public health officers at the state and local levels. “The response at the highest office in the land [is to ignore] data, science, and facts,” Grant Colfax, MD, director of the San Francisco Department of Public Health, told Carolyn Said in the San Francisco Chronicle. “That feeds into the local dynamics we’re seeing across the country.”

Public Health in the Limelight and Under Attack

In normal times, public health institutions operate in the background. As the Atlantic’s Ed Yong wrote, “Public health is not a calling for people who crave the limelight.” And because public health interventions focus on prevention of diseases, injuries, and infectious outbreaks, “the more successful public health is . . . the more people take it for granted.”

But during the coronavirus crisis, as in other public health emergencies, public health officers have been pushed into center stage because “communities depend on the ability of public health agencies to leap into action,” Trevor Wrobleski, a recent graduate of Johns Hopkins University, and Joshua Sharfstein, MD, vice dean for public health practice and community engagement at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, wrote in a USA Today opinion piece.

Public health officers have made critical decisions about how and when to implement shelter-in-place orders and face mask mandates. They weigh the trade-offs of reopening certain businesses but not others — all while information about the coronavirus is changing by the day. For their efforts, some public health officers have been criticized and physically threatened by residents and public officials who disagree with their decisions. “We are deeply concerned that politics may be trumping public interest in some of these cases,” California Medical Association president Peter Bretan Jr., MD, said in a statement.

“This is the beginning of a wave of [public health] people leaving. . . . Who would want to go work as a director in a public health department when you have a target on your back?”

—Theresa Anselmo, Colorado Association of Local Public Health Officials

In California, “at least eight public health officers across the state have left their posts during the COVID-19 pandemic,” Katrina Peters, MD, president of the Alameda-Contra Costa Medical Association, and Seema Sidhu, MD, president of the Santa Clara County Medical Association, wrote in a commentary for the Mercury News. Nationally, at least 27 state or local public health leaders have resigned, retired, or been fired since April, according to an analysis by Kaiser Health News (KHN) and the Associated Press (AP).

At an Orange County supervisors meeting in May, an attendee read aloud the home address of county chief health officer Nichole Quick, MD. Quick was given personal protection by the sheriff, but she resigned in June when the threats continued.

In Los Angeles County, Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer, PhD, MPH, started receiving death threats in May. “During a public briefing streamed on the county’s Facebook page, the health director said that her husband, children, and colleagues noticed that someone had posted a message in the comments section that ‘casually’ suggested she should be shot,” Colleen Shalby reported in the Los Angeles Times. Ferrer has opted to handle the county’s coronavirus briefings on her own to shield staff from similar attacks.

Dangerous Drop in Funding

Public health officers are fighting a pandemic in a system that has been defunded and deprioritized for years. A joint KHN/AP investigation found that spending for state public health departments has dropped by 16% per capita since 2010. Spending for local health departments has dropped 18%, and at least 38,000 state and local public health jobs have disappeared since the 2008 recession.

“We don’t say to the fire department, ‘Oh, I’m sorry. There were no fires last year, so we’re going to take 30% of your budget away.’ That would be crazy, right?” said Gianfranco Pezzino, MD, MPH, the health officer for Shawnee County, Kansas, told KHN/AP. “But we do that with public health, day in and day out.”

Understaffed and overworked during the pandemic, public health departments face staff burnout as COVID-19 cases climb and winter influenza season looms. Who will fill the vacancies if public health leaders continue to resign or be pushed out?

“This is the beginning of a wave of people leaving,” Theresa Anselmo, executive director of the Colorado Association of Local Public Health Officials, told Rachel Weiner and Ariana Eunjung Cha in the Washington Post. “Who would want to go work as a director in a public health department when you have a target on your back?”

Public Health Needs Support

In 2015, when Ebola was devastating West Africa, Bill Gates warned of the next epidemic, writing, “I believe we can prevent such a catastrophe by building a global warning and response system for epidemics.”

Now the world is paying dearly for its lack of preparation. There will be more viruses, and the US can do its part by bolstering its public health infrastructure with funding and trust.

“When it comes to public health threats, our nation needs to be overprepared, not underprepared,” Robert Redfield, MD, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), told lawmakers at a Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee hearing last month.

Nearly 7 in 10 Californians have confidence in the California Department of Public Health and in county public health departments.

That preparation could have started with Redfield’s agency, which “struggles with a slew of structural and cultural issues that have left [it] ill-equipped to fend off political attacks, or even to build up the political capital that could have helped it navigate the stark spotlight it finds itself in now,” Nicholas Florko wrote in Stat. Last week, those impediments got worse when the Trump administration stunned public health officials nationwide by ordering the CDC to cease collecting COVID-19 data.

It appears that most Californians, other than a small but vocal minority, trust the expertise of public health officers. A poll conducted by CHCF and global survey firm Ipsos found that nearly 7 in 10 Californians have confidence in the California Department of Public Health and in county public health departments.

Strong public-private partnerships can help reinforce Americans’ trust in public health. If enough brand names like Starbucks and Walmart mandate that customers follow public health guidelines in order to patronize their businesses, people may be more likely to follow suit and normalize that behavior. (Watch a recent San Francisco Business Times panel on how public health and business leaders can work together to safely reopen communities.)

Local health officials “have the training and access to the data needed to understand how this virus works, where testing and health care resources are needed, and what kinds of community responses can keep people safe,” CHCF president and CEO Sandra Hernández, MD, wrote in a commentary.

Georges C. Benjamin, MD, executive director of the American Public Health Association, told Stateline, “People who have been clapping every night for front-line doctors should be clapping for public health workers too. They are saving hundreds of thousands of lives.”

Authors & Contributors