One day in December, Ken Wottge was working from his San Diego home around noon when the notification popped up on his iPhone: Possible exposure to COVID-19 virus. It said the exposure had happened five days earlier.

His first reaction was joy. “It was like, ‘Wow. This is kind of cool.’ The second was ‘OK, and what does that mean? What do I have to do?’” He clicked the link and found out that COVID tests were most accurate if taken three to seven days after exposure.

“I was going to run a few errands,” said Wottge, 56. He changed plans and got tested that afternoon; the test was negative. There was other information on the notification website too. “It answered all my questions,” he said.

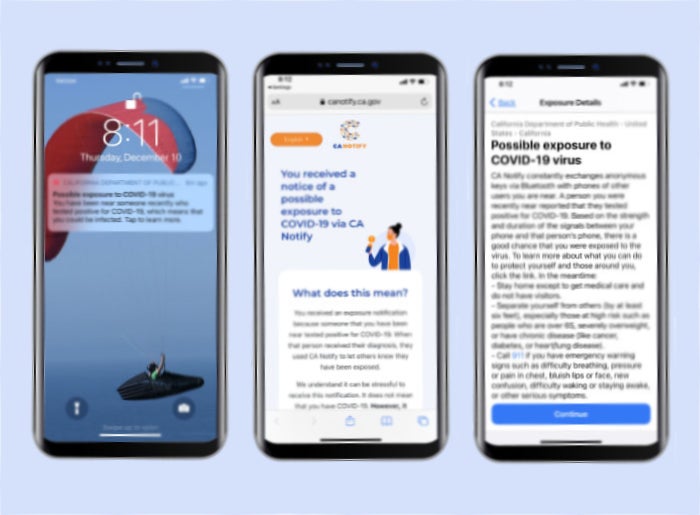

California launched the exposure notification app, called CA Notify, statewide on December 10. The app employs a framework released jointly by Apple and Google, and uses specifications set by the state departments of public health and technology. It provides an alert if the phone’s user has been exposed to an infectious person who had also enabled the app on his or her phone. Wottge had installed the app three months earlier, when a pilot began for students and employees at UC San Diego and UC San Francisco. He is director of information security at UC San Diego Health but was not directly involved with the pilot.

Since the launch, it has almost certainly prevented some infections, according to preliminary studies of similar technology used elsewhere. Precisely how many is an open question.

CA Notify is a simple application that is also being used in nine other states and the District of Columbia.

“I think that when the data comes out it will show that unquestionably it helped,” said Dr. Christopher Longhurst, the chief information officer for UC San Diego Health, who led the pilot there and oversees the health system’s current contract to manage parts of the statewide operation. He has been impressed by anecdotal data from the pilot, including a feature that enables users to share stories, as well as experience in other countries like the UK. With new infections down more than 90% in the state since the December peak, and built-in privacy protections that make outcomes analysis challenging, the data might not be published until the pandemic is nearly over, he said.

CA Notify is a simple application that is also being used in nine other states and the District of Columbia. All rely on the same Exposure Notifications Express system from Apple/Google.

Apple software updates last year embedded the technology in all iPhones made since 2014. To opt in on those iPhones, users can go to Settings, then Exposure Notifications, then Turn on Exposure Notifications. Tap Continue. Select United States and California.

Android phones require users to download the free app from the Google Play store; it too will operate on phones made since 2014.

The app runs in the background with Bluetooth Low Energy technology that continually pings nearby enabled phones without excessively draining batteries. Each phone uses constantly changing secret codes to keep a log of phones that spent more than a cumulative 15 minutes within six feet of it over the previous 14 days. That is the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guideline for the conditions that are most likely to allow viral transmission and the period of time that an infected person is considered contagious.

Someone who tests positive gets a text from the California Department of Public Health (CDPH) within a few days (the person’s health care provider may have told them already). The text will contain a validation code that can be voluntarily entered in the app. The phone then notifies all app-enabled phones that were close enough to it for enough time to constitute a potential exposure. Notifications give the date but not the location or any identifying information. (Neither the state nor the tech companies have access to the log of nearby phones, and all secret codes are deleted after two weeks.)

A Complement to Contact Tracing

This technically isn’t “contact tracing,” which involves health workers calling people who test positive, asking for the names of everyone with whom they were in close contact and then calling all those people. Contact tracing has long been the gold standard for limiting infectious disease outbreaks and is particularly successful for sexually transmitted infections like HIV.

It doesn’t work as well with viruses that spread on droplets and through the air. Who can remember the person they chatted with in a long supermarket line 10 days ago? A smartphone app does. Health officials caution that apps are intended to complement traditional contact tracing, along with social distancing, masks, and other measures.

The Apple/Google system did not go through a US Food and Drug Administration approval process, as most medical devices do, and neither the tech companies nor public health authorities have released much data on such things as how often smartphones successfully inform each other about exposures.

The research that is available depends at least partly on modeling. A small, non-peer-reviewed study of data early in the pandemic suggested that if only 15% of the residents of three counties downloaded the app, around 6% of deaths could be avoided, rising to more than half if 75% of residents downloaded it. An analysis released last month by Britain’s National Health Service (NHS), also not peer-reviewed, found that its similar app had notified 1.7 million people in England and Wales about possible exposure and that it theoretically prevented 600,000 cases.

Joanna Masel, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Arizona in Tucson, said the NHS study made a convincing case that the app “has made a sizable impact on disease transmission in the UK.” Masel, who led recently published research, not yet peer-reviewed, of a pilot at her own school, said she was “also persuaded that it has made a difference on the University of Arizona campus (PDF), based both on the data we presented” and “other data not yet public.”

Research so far has used available data to project the likely impact. “In my opinion, the biggest caveat to . . . these studies is that we do not know the degree to which people change their behavior once they receive an exposure notification,” Masel said in an email message.

Technology Appears to Be Effective

She and public health officials in other states like Hawaii, whose app is nearly identical to California’s, say the technology appears to be effective at reducing infections. “We believe that the AlohaSafe Alert exposure notification tool is making a real impact and has already prevented at least some COVID-19 infections here in Hawaii by allowing people to be informed of their exposure and to safely quarantine,” said Josh Quint, an epidemiologist with the state’s department of health.

Most UC San Diego students enabled their app during the fall pilot project, which was part of an initiative to bring students back to a safe campus. The pilot was reassuring, Longhurst said.

He calls the statewide experience a “mixed bag.”

“Nine million [downloads] is a pretty good number, and I’m bullish about that,” he said. “On the other hand, 8 million are iPhone users.” Surveys show iPhone users are more likely to be affluent, White, and tech workers. “The essential workers at the grocery store or the fast-food restaurant are more likely to be Android users and appear less likely to have activated the system.” People over 65, another vulnerable group, are less likely to own any kind of smartphone.

Another disappointing measure: Less than half of CA Notify users who test positive elect to enter the code to start notifications of others.

Why? Some people who already know they are positive might miss the CDPH text containing the code, or they may think it is spam. Others may fear being judged if someone figured out who they were. People with lower incomes tend to work longer hours and have less time, and people in general may be dealing with “the exposure itself,” said Elissa M. Redmiles, a researcher affiliated with Germany’s Max Planck Institute for Software Systems, who has studied why people may or may not download exposure notification apps.

People want to be able to trust the distributor of an app to protect their health data, she said. Although she didn’t examine survey respondents’ trust in health systems, she said it made sense that UC San Diego Health would get greater participation in its pilot than even the state health agency would.

Many Americans also want to know how accurate an app is before using it. “Even getting like half of their exposures would be good enough,” Redmiles said. While the state’s detailed Q&A (PDF) addresses privacy concerns, it says nothing about accuracy. For instance, Bluetooth signals are affected by the environment. Would you get a notification about someone with Covid sitting three feet away in the next apartment? Even the state’s weekly download numbers are given only to journalists.

Privacy Advocates Give Cautious Thumbs Up

Lack of transparency is a lingering issue for privacy advocates, who, after sounding the alarm early on, now say they are largely pleased with how the tech companies designed this app with privacy in mind.

Still, “there should be more robust and public security testing,” said Kurt Opsahl, deputy executive director and general counsel for the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a San Francisco–based group that advocates for digital privacy. And he would like guarantees from public health authorities and Apple and Google that once the pandemic is over and the app no longer needed, they will “turn it off.”

Longhurst mainly wants more people to use the app, especially in communities at high risk, and believes that more targeted outreach could help. Although push notifications went out to most smartphone owners, the FDA authorized the first vaccine the day after the app launch, shifting “all the attention and momentum,” he said.

Philip Tajanko, 19, downloaded CA Notify at home in Chicago before flying to San Diego last summer for his first year of college. He was vigilant about social distancing and wearing a mask, and he attended just one in-person class a week. Two weeks later, his routine COVID-19 screening test came back positive. He immediately entered the validation code and headed into isolation.

He could think of only eight people he might have been in contact with, including his four roommates. None of them had downloaded the app. “I had to do it by phoning them. Which is a lot more hassle,” Tajanko said.

Most eventually opted in.

Authors & Contributors

Don Sapatkin

Don Sapatkin is an independent journalist who reports on science and health care. His primary focus for nearly two decades has been public health, especially policy, access to care, health disparities, infectious diseases, medical research, and behavioral health, notably opioid addiction and treatment. Don previously was a staff editor for Politico and a reporter and editor at the Philadelphia Inquirer. He earned a bachelor’s degree from Haverford College and is based in Philadelphia.

David Poller

David Poller has worked as a photojournalist at newspapers and international wire services from Miami to Alaska. He shoots editorial and commercial assignments in Southern California and is a photo editor for the New York Times. Poller is a member of the National Press Photographers Association and the Association of LGBTQ Journalists.