|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready…

|

In 2015, executives at Partnership HealthPlan of California, a managed care plan for Medi-Cal enrollees in Northern California, launched an experiment. They’d noticed a trend: With the progression of serious illnesses, people often experienced symptom crises and their time in the hospital spiked. This made patients and their caregivers miserable. It also cost the health plan a lot of money.

James Cotter, MD, MPH, Partnership HealthPlan’s associate medical director and his boss, Chief Medical Officer Robert Moore, MD, MPH, MBA, were keen followers of a growing practice called palliative care. It’s a type of whole-person care that helps patients cope with the suffering and stress of serious illness by providing pain and symptom management, guidance on making treatment decisions, connections to social services, and emotional and spiritual support. Some plan members at the time already received palliative care when they were a hospital inpatient. But Cotter and Moore wondered if fewer patients would need hospitalization if they got palliative care at home.

CHCF Releases Palliative Care Resources as Grantmaking Shifts

CHCF is a proud contributor to advancing palliative care, both as grantmaker and coalition builder. Since starting this work in 2007, we’ve witnessed significant growth from a small set of early innovator programs reliant on in-kind support from health systems and philanthropic dollars, to a well-established specialty accessible in many settings and funded through Medi-Cal and some Medicare and commercial managed care plans.

Given this significant progress, CHCF is stepping away from active palliative care grantmaking. Many opportunities for growth remain, especially as California responds to a growing population of older people.

With this in mind, we have created two resources in collaboration with Transforming Care Partners that we hope can provide guidance, inspiration, and practical tools for the many stakeholders working to improve care for people with serious illness. They are:

• California’s Palliative Care Evolution: Celebrating Progress and Shaping the Future. This report sums up the progress in palliative care and opportunities for advancement in the next 5 to 10 years.

• The Health Plan Accelerator for Palliative Care. A toolkit for health plan champions interested in growing palliative care within their own organizations.

—Kate Meyers

With support from the California Health Care Foundation (CHCF), they launched a pilot program. Over a six-month period, the plan enrolled 82 people with serious advanced illnesses in home-based palliative care. The results were astounding: 95% of patients approved of the program. And Partnership HealthPlan saved $3 in hospital costs for every $1 spent on palliative care. Today, palliative care is available to all eligible plan members.

“The cost of the program is pretty high but, even still, hospitalizations are so expensive that [reducing avoidable hospitalizations] pays for all that,” Cotter said. “The members get better care, better service, better caregiver support, and we get fewer patients in the hospital. So, it’s a win-win.”

Collaborating to Improve Outcomes

Palliative care has taken root in California over the past 15 years, driven by hundreds of leaders within health plans, hospitals, clinics, home care agencies, advocacy and education organizations, and state government. Once little known and sparsely available, palliative care is now increasingly common in inpatient settings (especially larger hospitals) and growing in outpatient settings. Some of California’s greatest palliative care progress has been accomplished in programs serving people at the lowest income levels through the state’s Medi-Cal program and through public health care systems.

This growth emerged from the dedication and collaborative work of hundreds of health care leaders who built the awareness, research base, clinical capabilities, workforce, and payment mechanisms to deliver palliative care at scale. To celebrate this achievement and reflect on the work that remains to ensure that palliative care is available to all who need it, CHCF recently released a resource titled California’s Palliative Care Evolution: Celebrating Progress and Shaping the Future. An accompanying toolkit, Health Plan Accelerator for Palliative Care, offers guidance for health plan champions interested in launching or expanding palliative care within their own organizations.

“We’ve learned a lot, and our partners have learned a lot, about what it takes to build a successful palliative care program,” said Kate Meyers, MPP, a senior program officer with CHCF who since 2017 has led the foundation’s efforts to support the growth of palliative care. “Everyone whose work affects the care of people with serious illness has an important role to play to advance palliative care — our ‘California’s Palliative Care Evolution’ resource makes those opportunities and actions clear, so there’s no excuse not to lean in.

“Health plans play an especially critical role, so we supported the accelerator toolkit to help the health plan staff member who might be the lone person thinking about these issues or who has been tasked with developing a palliative care program. This information hopefully will inspire and inform them.”

The Case for Palliative Care

Palliative care can support people at any stage of a serious illness and can be provided alongside curative treatment. (This is a critical distinction from hospice care, which is generally restricted to people with a prognosis of six months or less to live who forgo treatments aimed at changing the course of the disease.) Specialist palliative care programs are delivered by a team of trained professionals that can include physicians, nurses, social workers, chaplains, and even pharmacists, and can be offered in hospitals, clinics, nursing facilities, and at home.

A mountain of research points to the benefits of palliative care, including improved clinical outcomes, enhanced patient experience, better patient and caregiver quality of life, and cost savings. Emerging evidence indicates improvements in clinician experience when their patients receive palliative care, and anecdotal feedback suggests it also improves the morale of other providers treating a patient by saving them time and helping address challenges such as difficult-to-control symptoms, social needs, complex family dynamics, and sensitive conversations about prognosis and goals of care.

Formal research aside, anecdotes abound about the power of palliative care: the man who stopped showing up in the emergency room after his home-based palliative care team realized all he needed was transportation to get to his regular doctor’s appointments, and the exhausted caregiver who finally got a break after a palliative care-trained social worker helped her apply for government assistance to pay for home help.

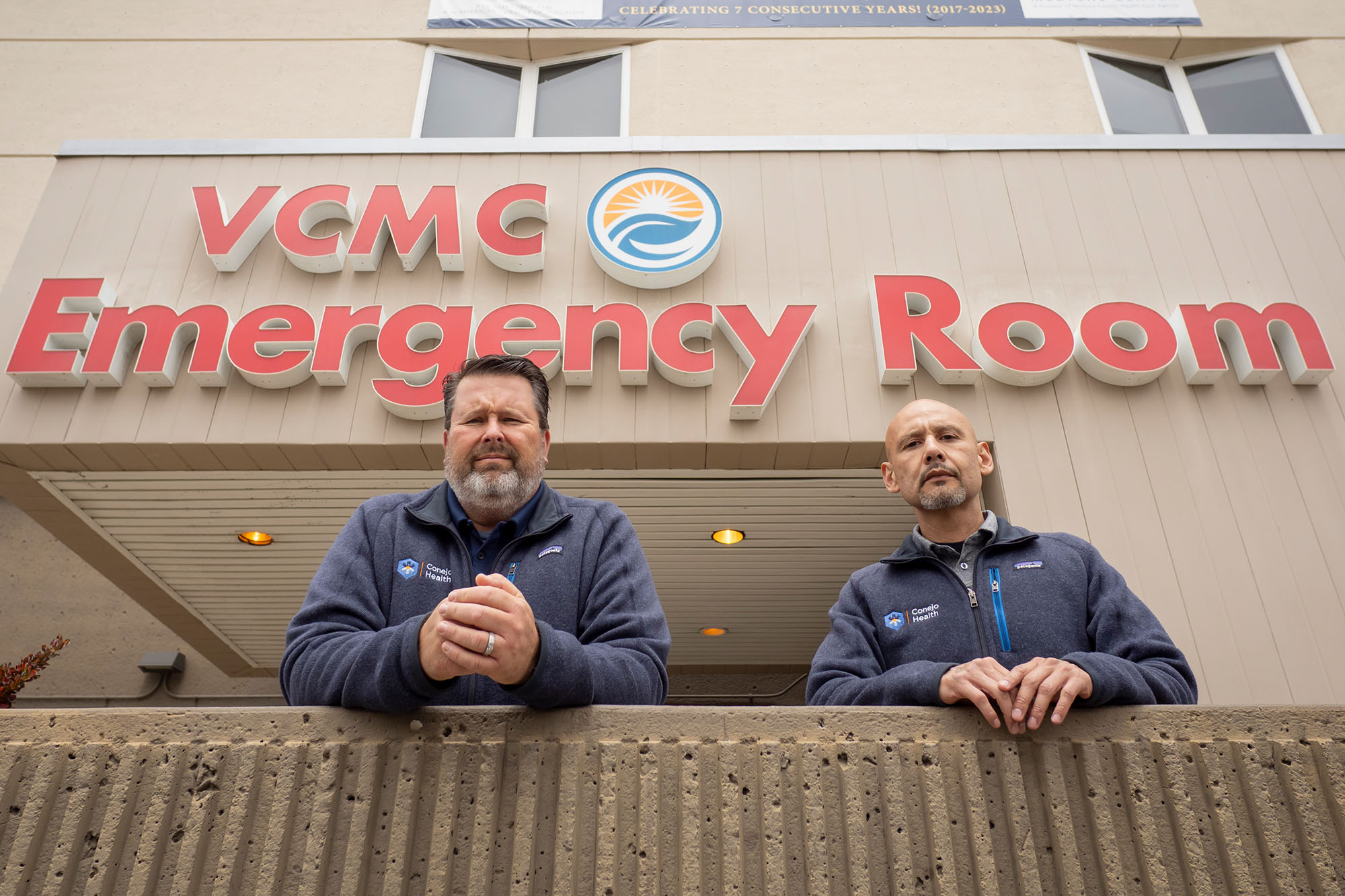

At Los Angeles General Medical Center, a large county hospital, a palliative care program launched by a single physician in 2007 has grown to a team of three physicians, a social worker, and a chaplain serving 500 to 800 patients a year. Chief of Palliative Medicine Carin van Zyl, MD, said the team members build trust with patients and caregivers and are often the only providers familiar with the patient’s entire history and circumstances. They communicate with other providers at the hospital to ensure that patients receive the most appropriate care, reducing needless suffering and repeat visits. She recounted how this helped one woman with a painful hip cancer stay out of the emergency room as her illness progressed.

“This is not work that requires a million-dollar MRI machine, or a $150,000-per-dose oncologic drug,” she said. “This is sitting at a bedside, pulling up a chair, having a human conversation with another human that results in all of this good. It’s not magic. It’s time, attention, and presence, and the payoff is just so huge.”

SB 1004 and Other Advances

A defining moment in the advancement of palliative care in California came in January 2018, when the state began implementing Senate Bill 1004 (SB 1004). The law led to California becoming the first state in the nation to require Medicaid managed care plans to give all eligible members access to palliative care.

Anastasia Dodson, MPP, deputy director at the California Department of Health Care Services, said it took three years after the bill’s passage in late 2014 to develop guidance on eligibility, services, and other protocols needed to implement the mandate. The state consulted with existing palliative care programs, such as the one at Partnership HealthPlan; held stakeholder meetings; scoured available research; and leaned into technical support provided by CHCF.

The result was “seismic” said Brynn Bowman, MPA, who leads the Center to Advance Palliative Care, a national advocacy organization.

“SB 1004 really was groundbreaking in terms of state Medicaid policy innovation, and we’ve already seen other states looking to California and hoping to follow in its footsteps,” Bowman said. “California’s example has really held up the need for equitable access to palliative care.”

In 2019, the requirement was extended to include pediatric Medi-Cal enrollees, replacing a previous palliative care program for children. As of January 2024, Dual Eligible Special Needs Plans in California are required to ensure access to palliative care for their seriously ill members. Other states now developing palliative care strategies for Medicaid include Hawaii, Washington, Oregon, Maine, and New Jersey.

Work Remains to Improve Care for Serious Illnesses

Despite California’s substantial progress, palliative care remains a relatively new medical discipline and is not yet as broadly integrated across the health care system as it should be to reach all those who need it. As a result, many patients, physicians, and even health plans don’t know about it or confuse it with hospice. Bridging this awareness gap is crucial to encouraging greater adoption of palliative care, said Loren Pogir, MPA, founder and managing partner of Transforming Care Partners, and primary author of CHCF’s recently released resource and health plan toolkit.

Equitable access is another concern. Health care leaders need to gather data on use of palliative care services among different race and language groups and conduct outreach to these populations to ensure that all eligible Californians know about and feel comfortable accessing palliative care, Meyers said. There’s also room to expand palliative care within for-profit health systems, community-based settings, and in rural areas, Bowman said.

And while field leaders have done a lot of work to define high-quality palliative care and codify standards and measures, these have not been universally adopted. Variation in services persists, which can make it difficult for referring physicians and patients to know what to expect, Pogir said. Workforce shortages are another challenge. California and other states can spark growth in palliative care by creating training and fellowship programs to educate the clinicians needed to provide it, Bowman said.

For health care leaders interested in establishing or expanding palliative care within their own organizations, communication is key. Van Zyl said she had to learn how to speak the language of “C-suite” executives and understand what they cared about to build the case for expanding the program at LA General (see the Transforming Care Partners toolkit for more information on this topic). Cotter, meanwhile, emphasized the importance of regularly meeting with his plan’s palliative care providers to identify and solve problems. Partnership HealthPlan also conducted years of outreach to providers and the public to build referrals.

The expansion of palliative care over the past 15 years means there are now plentiful resources and networking opportunities for people to draw on when building a program. “You do not have to figure this out on your own,” said van Zyl. “Use the resources that people have accumulated over time. Use the wisdom. . . . There’s no heroism in trying to reinvent it yourself.”

Pogir agreed that building a palliative care program takes effort. But in conducting in-depth interviews with over 30 health care leaders and facilitating cross-discipline working sessions on palliative care at a summit with more than 200 participants, she said, the overwhelming consensus is that the results are worth it.

“It takes up-front work and focus to get a program started,” she said. “But once the program is underway, health plan leaders consistently observe the positive reception from patients and their families, as well as health plan staff. It has tremendous payback for anyone who touches the health plan.”

Authors & Contributors

Claudia Boyd-Barrett

Claudia Boyd-Barrett is a longtime journalist based in Southern California. She writes regularly about health and social inequities. Her stories have appeared in the Los Angeles Times, San Francisco Chronicle, San Diego Union-Tribune, and California Health Report, among others.

Boyd-Barrett is a two-time USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism fellow and a former Inter American Press Association fellow.

Aaron Rosenblatt

Aaron Rosenblatt is a documentary photographer based in Oakland, California. His work has been published by The New York Times, the Associated Press, and the Guardian, and he has photographed for newspapers all over the US, including South Dakota, Vermont, Pennsylvania, and Missouri.

He currently works as a staff photographer for the Daily Republic in Fairfield, California, where he has documented farming and drought issues, wildfires, the housing crisis, and lucha libre.

Nancy Newman

Nancy Newman is a Southern California-based photojournalist and commercial photographer with extensive experience in news and portraiture. In more than 25 years in the industry, she has often focused on subjects in the worlds of health care, education, business, philanthropy, public relations, sports, entertainment, and fashion. She enjoys applying her documentary photojournalism style of photography to help clients achieve their editorial and marketing objectives.

Newman worked for newspapers and magazines before she started her own photography business and now serves local, national, and international clients. Her photographs have been published in more than 17 countries and have garnered multiple awards.