California has no shortage of patients. Thanks to the Affordable Care Act, a record 93% of the state’s nearly 40 million residents are insured. Unfortunately, the state doesn’t have enough health care professionals to care for them all — a shortage that experts predict will only worsen with time.

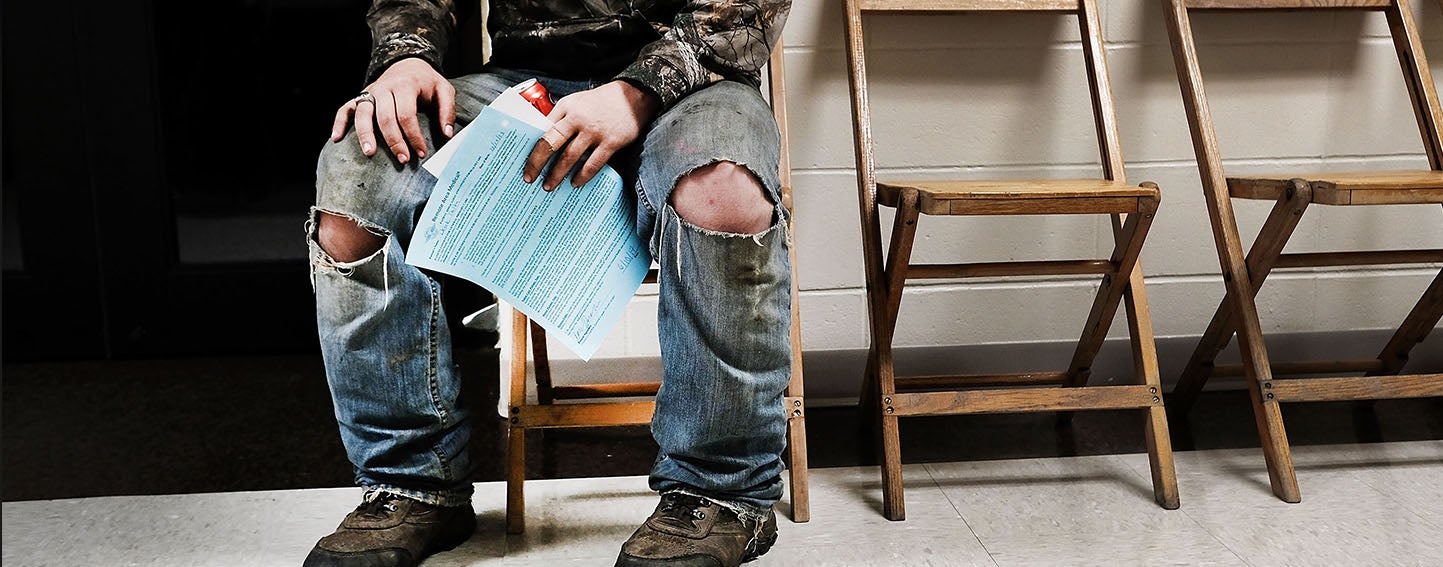

In the Sacramento Bee, Hannah Holzer highlights two particularly concerning trends. First, California faces a shortage of mental health professionals. A study funded by the California Health Care Foundation (CHCF) and conducted by researchers at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Healthforce Center projected that by 2028, the state will have 41% fewer psychiatrists — and 11% fewer psychologists, marriage and family therapists, clinical counselors, and social workers — than it will need. This shortage will be especially challenging for people in rural areas like Grass Valley, where residents already need to drive for hours to reach the nearest mental health specialist. “The shortage of psychiatrists in the United States and California has reached crisis levels,” said Assemblyman Brian Maienschein of San Diego.

Second, the state’s capital doesn’t have enough obstetrician-gynecologists (ob/gyns) to meet its needs. Among metropolitan areas with the greatest shortage of ob/gyns, Holzer reports that Sacramento ranks ninth. This bodes ill for women living in the Sacramento area. In addition to providing routine women’s health care, ob/gyns provide essential care to expectant mothers before and during childbirth. Without an adequate workforce to care for all mothers, it is more likely that “women get suboptimal care and die,” said Amy Autry, MD, of the UCSF department of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences.

Health workforce shortages are driven by common issues: an aging workforce and a growing population, physician burnout, lack of residency programs to train future providers, and — especially in underserved areas — low reimbursement rates in a state with a high cost of living.

Building the Workforce of the Future

The good news is that California has begun prioritizing solutions to tackle its health workforce crisis. This week, L.A. Care Health Plan announced a $31 million initiative dubbed “Elevating the Safety Net” to address health care access in high-need areas and safety-net clinics. Sara Heath writes at PatientEngagementHIT.com that the funding will provide financial awards to clinicians pursuing careers in the safety net. “These [medical] students won’t have to carry a loan the size of a home mortgage when they graduate,” said L.A. Care’s CEO John Baackes. “Our hope is that the relief from that financial burden will enable them to pursue their passion for serving the underserved.”

Medical programs have sprung up in underserved areas that previously had no training base for aspiring physicians. In the Fresno Bee, Barbara Anderson writes about the UCSF School of Medicine’s newest branch campus in Fresno. Through the San Joaquin Valley Program in Medical Education (SJV PRIME), UCSF students will spend a year and a half at the San Francisco medical campus before moving to Fresno for their final two and a half years of training. Fresno is located in the medically underserved San Joaquin Valley, and SJV PRIME administrators hope the students will apply for residencies there upon finishing their program.

Further south, in Coachella Valley, the desert region is seeing the first signs of success from a University of California, Riverside (UCR) School of Medicine residency program designed to address the region’s physician shortage. In the Palm Springs Desert Sun, Sherry Barkas reports that the residency program, which is a partnership between Desert Regional Medical Center, Desert Healthcare District, and the UCR School of Medicine, recently graduated its first class of residents. Out of a class of seven residents, six are staying local to serve the valley. “UCR School of Medicine is very unique,” said program director Gemma Kim, MD. “It is one of very few that promotes primary care… and really wants to address the physician disparities that exist in the county and ensure that they meet those needs.”

A statewide effort to identify solutions to the health workforce shortage is also underway. Last year, the California Future Health Workforce Commission made its debut with a 24-member commission cochaired by University of California President Janet Napolitano and Dignity Health President and CEO Lloyd Dean. The commission is composed of top leaders in California health care, higher education, and business, and is funded by Blue Shield of California Foundation, The California Endowment, The California Wellness Foundation, and CHCF.

Guidelines Sidelined

If the federal government pulls the plug on a popular health care database without warning, does it make a sound? Apparently, yes, thanks to some hard-nosed government watchdogs and data pros. This week, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), part of the Department of Health and Human Services, quietly deleted a database known as the National Guideline Clearinghouse (NGC). Jon Campbell, senior investigator for the Sunlight Foundation’s Web Integrity Project, writes in the Daily Beast that the NGC “is perhaps the most important repository of evidence-based research available.” It not only provides doctors with a “cheat sheet” for making clinical decisions, but also acts as a gatekeeper to reject weakly supported research or information biased by industry groups.

AHRQ said the decision to shut down the NGC was purely financial, even though the database receives about 200,000 visitors, mainly physicians, per month. An AHRQ spokesperson told Campbell that the operating budget for the NGC last year was $1.2 million, and that federal cuts to AHRQ prevent it from continuing support for the database.

On July 16, the NGC went missing from the AHRQ website. But that’s not the end of this story. A multi-sector working group labored through the night of the 15th to create a mirror of the database. Fred Trotter, a self-proclaimed “hacktivist” who works on health IT and was part of the working group, tweeted on the afternoon of July 16 that the group successfully created a mirror backup of the NGC. You can read about the group’s efforts in detail on Trotter’s website.

There’s no shortage of important health care stories out there. What was the best one you read this week? Email me.

Authors & Contributors