California is preparing to expand Medi-Cal to inmates up to 90 days before release as part of the latest transformation to the state’s low-income health insurance program.

Under the expansion, incarcerated people with a variety of health issues, including chronic conditions, mental illness, substance use disorders, disabilities, or who are pregnant will be eligible to receive assessment and treatment shortly before release. The goal, in part, is to facilitate a smooth reentry process and reduce costly emergency room visits and hospital stays.

Typically, Medi-Cal, which provides health insurance to residents with low incomes, is prohibited from servicing incarcerated people, but state officials have applied for a waiver from the federal government. The waiver is expected to be granted as soon as mid-January, according to Jacey Cooper, director of the state’s Department of Health Care Services. The state is also requesting $561 million to implement the changes.

“If we’re serious about closing equity gaps within our health system and with our Medi-Cal beneficiaries, we think that we need to focus on the prison and jail population to make sure we’re doing what we can to have a coordinated reentry,” Cooper said.

California has spent the past six years testing various changes to Medi-Cal and submitting evidence to the federal government on resulting improvements in access, quality, and cost. The approaching waiver approval sets the stage for the federal government to ease restrictions on publicly funded health care for people behind bars.

“It’s a policy that’s been in place for so long, and it’s such a discriminatory and racist policy in many respects. To tackle it in this way is huge,” said Dr. Clemens Hong, acting director of community programs with Los Angeles County’s Department of Health Services.

Prior to seeking the waiver, state lawmakers passed a measure requiring eligible inmates to be automatically enrolled in Medi-Cal upon release. That law took effect January 1. Approximately 80% of California’s incarcerated population qualifies but can face long delays between release and the start of their Medi-Cal services. The changes are part of the state’s efforts to improve health outcomes and reduce costs under an initiative called CalAIM that began in early 2022.

The criminal justice expansion is one of the last major CalAIM changes planned for Medi-Cal. Previous changes include raising health outcome benchmarks, integrating behavioral health services, requiring case management for some enrollees, and paying for non-medical services (PDF) like housing and air quality remediation.

Health Disparities Among the Incarcerated

Many of the changes made to Medi-Cal have focused on addressing patients with complex social and health needs, including the incarcerated population.

“We know the [incarcerated] population is particularly at risk of poor health outcomes,” Cooper said.

Research shows people who have spent time in jail or prison face much higher rates of physical and behavioral health diagnoses. Nationally, more than 26% of former inmates have high blood pressure compared to 18% of the general population, and 15% have asthma compared to a general rate of 10%. Within the first two weeks of release, the death rate among formerly incarcerated folks is 12.5 times higher than average, driven largely by overdoses.

In California, two-thirds of people in prison and jail require addiction treatment, and the number of incarcerated individuals being treated for mental illness has increased 63% in the past decade, according to state data. The incarcerated population in California is also disproportionately people of color, with Black men making up nearly 30% of incarcerated males compared to only 5% of the state’s overall population.

These chronic and complicated health needs make former inmates some of the most expensive patients. Medi-Cal data shows recently incarcerated people average around $4,000 in emergency room and hospital bills within the first year of release compared to $1,000 among Medi-Cal members without a history of incarceration, Cooper said. They are also 10 times more likely to become homeless.

Contributing to poor health outcomes are the myriad socioeconomic challenges formerly incarcerated people face upon release, said Dr. Shira Shavit, family medicine doctor at UCSF and executive director of the Transitions Clinic Network, which helped pilot the new services in several counties.

“When people are reentering the community, they’re set up to fail, not just on the medical front, but housing, family reunification, employment,” Shavit said. “All of their basic needs are up in the air at the same time, and it’s very challenging for people to rebuild their lives, especially while also dealing with health conditions.”

Shavit’s work has shown that with the right support, health and social outcomes for recently incarcerated people can improve significantly. They have fewer hospitalizations, half as many emergency room visits, and fewer parole violations. Under the state’s proposal, incarcerated folks would be released with any necessary medical supplies, like medication or wheelchairs, and connected with doctors and community health workers.

“If you take a look at the bigger picture, it’s a really important time for health care to say we play an important role,” Shavit said.

Community Health Workers at the Forefront

Advocates for incarcerated folks say connecting recently released people to health care is an essential part of improving reentry programs aimed at keeping people from returning to prison.

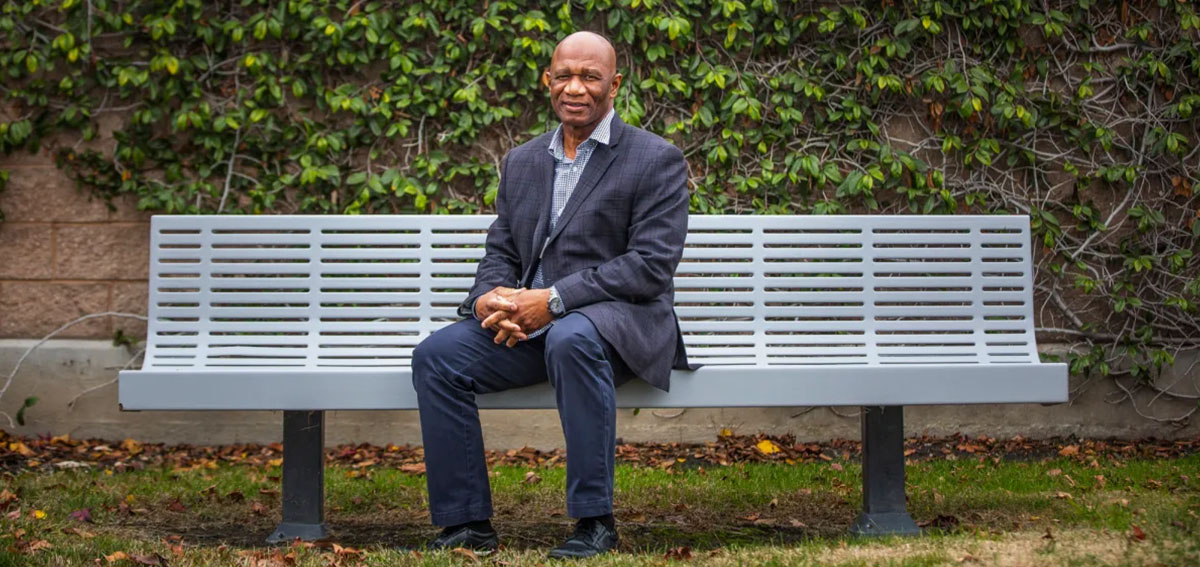

“Ninety percent of people are going to be returning at some point to the community. And this is just part of not only helping that individual, but our community to be healthier and safer,” said James Mackey, clinical case management supervisor at Community Medical Centers in Stockton. “In the long run, that’s what everyone wants.”

Mackey was imprisoned for 28 years for first-degree murder. He earned a master’s degree in humanities while incarcerated, recently earned another master’s in social work and has spent much of the time since his release as a community health worker in Stockton. He now manages the Transitions Clinic Network program in the area, talking to doctors about his clients’ needs, encouraging community groups to give people with a history of incarceration a second chance and assisting about 80 recently released people at any given time.

There’s no standard procedure for release, Mackey said. Frequently, people are taken to the nearest bus station and “cut loose,” he said, a daunting and disorienting change for someone who may have been behind bars for decades with no connections on the outside.

That’s where community health workers come in. Portions of CalAIM implemented earlier this year already require Medi-Cal insurers to offer additional services like case management to high-needs users, like people with a history of incarceration or who are experiencing homelessness. That means having someone who can help you find a doctor, treatment center, housing or other social services, fill out paperwork, and ensure you get appropriate follow-up.

Having someone to lean on in those early days of release, particularly someone who has experienced time behind bars and is now able to give back, goes a long way toward getting people on the right path and rebuilding trust in the system, Mackey said.

“I came home five years ago after 28 years, and it was scary,” Mackey said. “[But] every time someone treated me like a human, it was easier for me to act like a human and feel like a human.”

CalAIM’s support for these services is a critical step toward improving health access and equity among people with criminal convictions, said Joe Calderon, a former Transitions Clinic Network patient and lead community health worker with the group.

“We need to remember that access does not equal engagement in my community,” Calderon said. “Many people coming out of prisons have a healthy mistrust of systems.”

Calderon was imprisoned for 17 years for second-degree murder. He has worked for the past 12 years in public health with the Transitions Clinic Network. Calderon had a family history of deaths resulting from cardiovascular disease. While behind bars, he was diagnosed with high blood pressure. Upon release, his community health worker helped him sign up for insurance, find a doctor, and get medication.

“I didn’t know how to get refills. I didn’t know how to navigate the medical system,” Calderon said. “I just knew that without those medications, like my father, I might just pop.”

Pilot Programs Show Promise

Across California, a handful of counties have piloted the new CalAIM provisions since 2016. Los Angeles County’s Department of Health Services used its pilot program to create reentry plans that addressed incarcerated people’s medical and social needs. More than 25,000 inmates met with social workers and community health workers shortly before release to determine what support they would need in the community. They were also released with a 30-day supply of any medication they were currently taking.

The pilot was the first coordinated effort in the county to bring health, social, and behavioral health services under one umbrella, said Hong, acting director of community programs at the health services department.

“There were pockets of [reentry services], but it wasn’t very consistent, and there wasn’t a consistent way to identify people with those needs,” Hong said. “It was quite fragmented.”

Los Angeles has the largest incarcerated population in the country, and the jail system doubles as the largest mental health institution in the nation. Up to 80% of the county’s roughly 14,500 inmates qualify for these services either by having a chronic physical or mental illness or a substance use disorder, Hong said.

“There’s a moral imperative to figure out how to move people who are sick into settings in which they get treatment and care rather than carceral settings where they don’t and where it can be actually detrimental to the health outcomes,” Hong said.

A county impact report (PDF) on the pilot program found the number of primary care visits increased by 12% in the first year following release and the number of emergency room visits decreased by 4%. Newly released inmates were difficult to keep track of, however, and about half were lost to follow up, Hong said. Federal approval of California’s Medi-Cal changes will allow the health services department to provide even more medical care prior to reentry, including prescribing medications and allowing specialists to visit patients behind bars.

Statewide, a 2020 assessment of CalAIM pilot programs (PDF) saw steep reductions in emergency room visits and hospital readmissions. In the first two years, the rate of emergency department visits among formerly incarcerated people decreased by 25% compared to the previous year. While hospitalization rates remained similar during the first two years of the pilot programs, readmission rates dropped by 12%. The rate of those who began addiction treatment also doubled.

The same report, however, found that recently incarcerated folks were the least likely to receive many of the new services CalAIM now requires Medi-Cal insurers to provide, including care coordination, housing assistance, peer support and benefit assistance.

Calderon, who helped train community health workers for LA County’s reentry division, said the state’s formalized expansion of Medi-Cal for inmates will need to be watched carefully to ensure it is done effectively.

“I want to make sure in California…that we don’t leave behind anyone because they have a felony,” Calderon said, referring to health and employment opportunities.

Helping people heal physically is also a pathway toward helping them make amends, he said. His personal experience and work with the Transitions Clinic Network has shown him that many formerly incarcerated people want to be part of the solution, they just need the tools to do so. Calderon’s own community health worker years ago was the first person to help him learn the skills to do the work he does today.

“Years ago if you asked me who Joe was, the definition would have been very different from what I know about who I am today. It came out of a lot of fire and a lot of pain and a lot of trauma,” Calderon said. “Now, I look back at everything, see the path, see a better way for others and advocate for that change in California, utilizing CalAIM hopefully to change systems.”

It’s a sentiment Mackey shared.

“I still have a lot of guilt and shame for my own crime,” Mackey said. “To be seen out there as representing something – it was kind of scary for me. I always wanted to just keep my head down. But you know, in the last few years, I’ve realized that if I’m going to be a part of this fight, I need to stand up and use my voice.”

This article was produced and first published by CalMatters on January 5, 2023.

Authors & Contributors

Kristen Hwang

Kristen Hwang reports on health care and policy for CalMatters. She is passionate about humanizing data-driven stories and examining the intersection of public health and social justice.

Prior to joining CalMatters, Kristen earned a master’s degree in journalism and a master’s degree in public health from UC Berkeley, where she researched water quality in the Central Valley. She previously worked as a beat reporter for The Desert Sun and a stringer for The New York Times California COVID-19 team.