Earlier this year, when public schools in Kansas City, Missouri, shut down in-person instruction because of the COVID-19 pandemic, Nika Cotton quit her job in social work to start her own business. She has two young children — ages 8 and 10 — and no one to watch them if she were to continue working a traditional job.

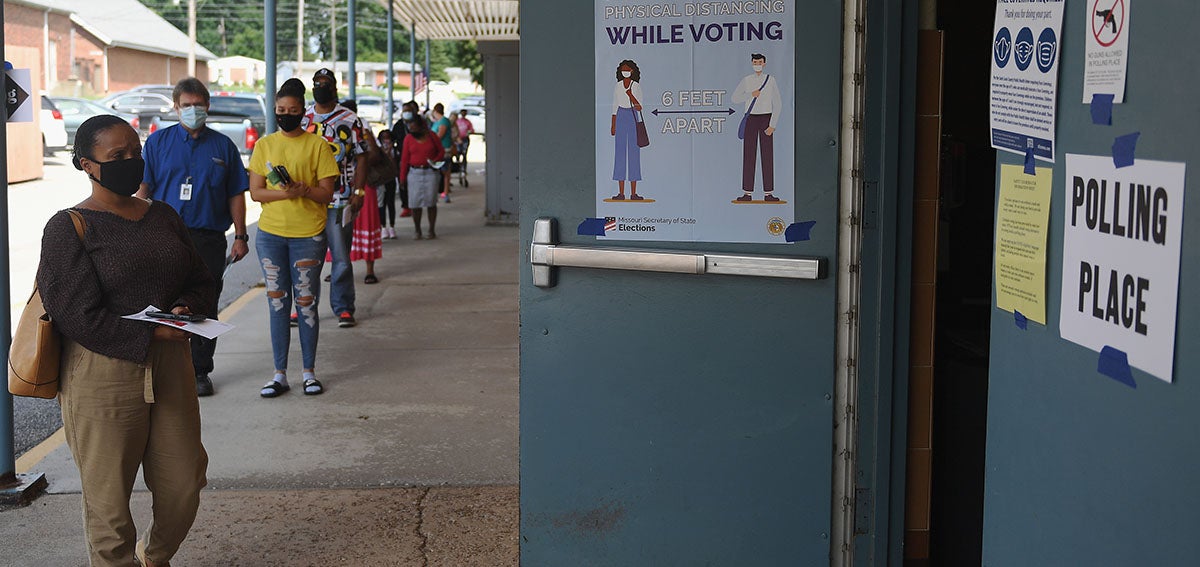

It was a big decision, made weightier by the loss of her employer-sponsored health insurance. But on August 5, Cotton awoke to the news that Missouri voters had narrowly approved the expansion of the state’s Medicaid program via ballot initiative, making it the second politically right-leaning state to do so during the pandemic. The expansion opens Medicaid eligibility to individuals and families with incomes up to 138% of the federal poverty guidelines, which are $12,760 for an individual and $21,720 for a family of three, allowing Cotton’s family of three to qualify.

“It takes a lot of stress off of my shoulders with having to think about how I’m going to take care of myself, how I’m going to be able to go and see a doctor and get the health care I need while I’m starting my business,” she told Alex Smith of KCUR, the NPR affiliate in Kansas City.

Research has shown time and time again the varied benefits of Medicaid expansion: lower mortality rates among older adults with low incomes, declines in infant mortality, reductions in racial disparities in the care of cancer patients, and fewer personal bankruptcies, just to name a few.

More than 1.25 million Missouri voters weighed in on the measure, with 53% voting for it and 47% against it. Missouri’s Republican governor Mike Parson opposed it, arguing that the state could not afford the coverage expansion — even though the federal government pays 90% of the costs and a fiscal analysis (PDF) by the Center for Health Economics and Policy at Washington University estimated that the state would save $39 million if it implemented Medicaid expansion in 2020.

The ballot measure requires the state to expand Medicaid by July 2021, and an estimated 230,000 residents with low incomes will become eligible for affordable health coverage.

Voters Signal Support

In late June, Oklahoma voters also approved Medicaid expansion by ballot measure, eking out a victory by less than one percentage point.

“It is difficult to ignore that these ballot initiatives passed in right-leaning states in the middle of the coronavirus pandemic, when millions of Americans have lost their jobs and, with them, their employer-sponsored health insurance,” Dylan Scott wrote in Vox. “This is partly a coincidence — the signatures were collected to put the Medicaid expansion questions on the ballot long before COVID-19 ever arrived in the US — but the relatively narrow margins made me wonder if the pandemic and its economic and medical consequences proved decisive.”

Earlier this year, Scott spoke to Cynthia Cox, MPH, director of the Peterson-Kaiser Health System Tracker, about the potential impact of the pandemic on health care politics. “Many of the biggest coverage expansions both in the US and in similar countries happened in the context of wars and social upheavals, as well as financial crises,” Cox said. “One theory is that those circumstances redefine social solidarity, thus expanding views of the role of government.”

Between February and May, Missouri’s Medicaid program saw enrollment rise nearly 9%, one of the largest increases nationwide during the pandemic, Rachel Roubein reported in Politico. During that same period, Oklahoma’s Medicaid program saw enrollment increase by about 6%.

States that implemented Medicaid expansion are better positioned to respond to COVID-19, according to a report by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP). These states entered the health crisis and resulting economic downturn with lower uninsured rates. This is important for public health “because people who are uninsured may forgo testing or treatment for COVID-19 due to concerns that they cannot afford it, endangering their health while slowing detection of the virus’ spread,” the authors wrote.

CBPP and KFF estimate that 3.6 million to 4.4 million uninsured adults would become eligible for Medicaid coverage if the 12 states that have not yet expanded the program did so. Those states are Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Kansas, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Wisconsin, and Wyoming.

Coverage for Frontline Essential Workers

During the pandemic, Medicaid is particularly important for frontline essential workers, such as those working in grocery stores, meat processing plants, and nursing homes. Their jobs require them to report in person, increasing their risk of getting sick with the coronavirus as they interact with coworkers and, in many cases, with customers and patients. Essential workers are often paid low wages and not offered employer-sponsored health insurance or can’t afford the premiums for it.

About 5 million essential workers nationwide get health coverage through Medicaid, “including nearly 1.8 million people working in frontline health care services and 1.6 million in other frontline essential services including transportation, waste management, and child care,” Matt Broaddus, senior research analyst at CBPP, wrote on the center’s blog.

In California, over 950,000 essential workers are enrolled in Medi-Cal, the state’s Medicaid program. People of color are overrepresented in many categories of essential jobs. According to a UC Berkeley Labor Center analysis of the 15 largest frontline essential occupations, Latinx workers are overrepresented in agriculture, construction, and food preparation, among other occupations. Asian workers are overrepresented among registered nurses and personal care aides; and Black workers are overrepresented among personal care aides, laborers and material movers, and office clerks.

In addition to low-wage workers, Medi-Cal continues to bridge the coverage gap for other key populations amid the COVID-19 crisis, which is magnifying historical health inequities. (Medi-Cal covers nearly 40% of the state’s children, half of Californians with disabilities, and over one million seniors. For a refresher on the program, see CHCF’s Medi-Cal Explained series.)

Even though Missouri’s Medicaid expansion won’t take effect for another year, Nika Cotton remains excited. “It’s better late than never,” she said. “The fact that it’s coming is better than nothing” — perhaps a takeaway for the remaining 12 states.

Do you think the COVID-19 pandemic is changing health care politics? Email me.

Authors & Contributors