|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready…

|

Artificial intelligence (AI) could revolutionize health care delivery, including for low-income and under-resourced populations, health policy leaders said at a recent Sacramento briefing sponsored by the California Health Care Foundation (CHCF). To ensure that AI benefits reach everyone and advance health equity, health care safety-net leaders must earn the confidence of patients and communities while building trust within the health care workforce, the leaders said.

AI technology could transform the diagnosis and treatment of disease, greatly reduce the burden of recordkeeping for providers, and streamline insurance and other bureaucratic processes. With its ability to quickly analyze colossal amounts of digital data, AI can help physicians identify health problems faster and more accurately. AI tools that take notes during patient visits and automatically update individuals’ electronic health records could give providers more time for meaningful interaction with patients while reducing the growing problem of provider burnout.

View the AI Briefing on Demand

Nearly 500 people watched the livestreamed April 25 event in Sacramento, and another 75 attended in person. Watch a video replay.

But the prodigious power of AI also carries risks. Research shows that computer algorithms can perpetuate the kinds of bias and inequity that have long exacerbated racial, ethnic, and geographic health disparities. The health care leaders identified numerous concerns about using AI in health care, including neutralizing threats to patient privacy, ensuring proper oversight, and addressing fears about AI tools being used to replace workers.

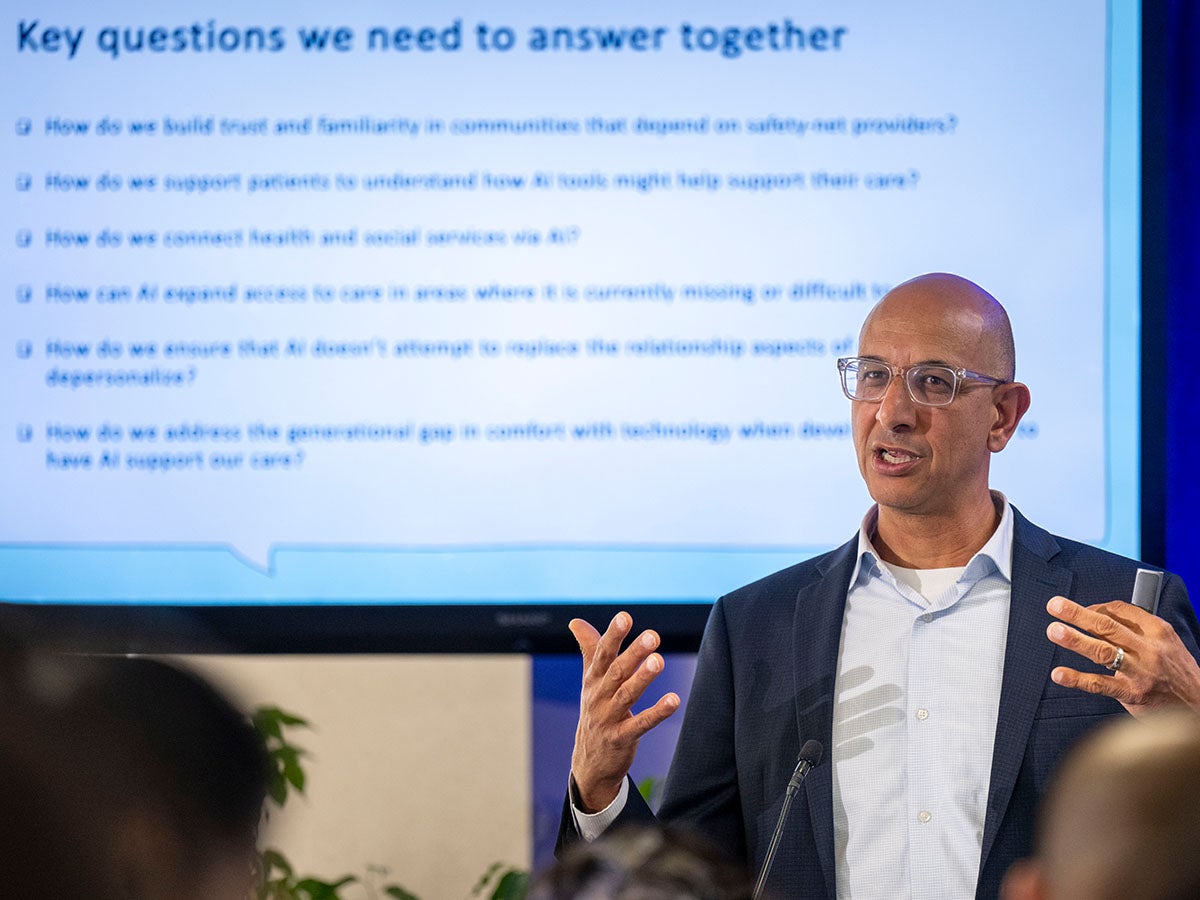

During the April 25 meeting, Mark Ghaly, MD, MPH, secretary of the California Health and Human Services Agency, urged safety-net leaders not to run away from AI because of the risks and concerns and instead to stand tall and grasp the opportunities it presents. “I believe that with us working together, with us eager to see what we can unleash with this technology, we can make California not just a leader for leading’s sake, but actually improve some of the health and social service outcomes that I know everyone in this room is interested in helping improve,” Ghaly said.

Other speakers said they worry about whether California hospitals and clinics serving communities that have traditionally faced the greatest barriers to care will be able to take full advantage of AI’s benefits. Those institutions have fewer resources than private health care providers and are slower to adopt new technologies. If mishandled, AI could prolong and entrench health disparities, some speakers noted. Meanwhile, policy and regulations have lagged behind as AI development speeds up.

What If AI Is Here to Stay?

“It’s so important not to be afraid of AI,” said Carolina Reyes, MD, an associate clinical professor in maternal-fetal medicine at the UC Davis School of Medicine, chair of the CHCF board of directors, and a board member of CommonSpirit Health, a nonprofit health system operating in 24 states. “I do think that it is here to stay and [is] going to revolutionize what we do.… We do need some guardrails, … but I do think that it’s going to help us be much better at our interactions and help us treat patients a little bit more humanely, I think, with a little bit more dignity.”

“Is AI going to be good or bad for health equity in California?” said Susan Ehrlich, MD, MPP, chief executive officer of Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital and Trauma Center and a professor of medicine at UCSF. “I’m on the cautiously optimistic side.… Optimistic because we’ve seen some incredible results from AI, but cautious because … it requires a huge amount of resources. It requires expertise, it requires time, and it requires a lot of money.”

Kara Carter, MBA, MSc, CHCF’s senior vice president for strategy and programs, said the ramifications of AI in health care are generating both excitement and concern across the California health care system.

“Over the past year, in almost every conversation I’ve had, in every part of the state, with all sorts of leaders, the topic of AI has risen to the top,” she said. “Why is that? Good reasons. The implications for AI [in health care] and in the rest of our lives are massive.”

Ghaly said his agency is assessing how best to utilize AI and wants to ensure that the safety net doesn’t get left behind. That includes figuring out how to balance the benefits of AI with the expense of implementation.

State health care officials are planning to adopt AI-driven processes to improve how the California Department of Public Health surveys health care facilities, he said. The department is also exploring generative AI (Gen AI) solutions to increase the speed, efficiency, and accuracy of patient language translations, so the nearly 20% of Californians with limited English proficiency can more easily learn how to access the health care and social services they need. (A subset of AI, Gen AI creates new, original content from analyzing extensive source material.)

Other important challenges include addressing worker and community mistrust toward AI, making sure the technology doesn’t weaken patient-provider relationships, and addressing varying attitudes toward AI, Ghaly said. He invited audience members to direct their thoughts to his office.

How Are Health Systems Using AI Now?

Deployment of AI technology by the health care delivery system is well underway, with promising results, panelists said. Doctors at UC Davis Health have adopted AI to rank chest x-rays in order of severity, so that patients with more significant problems get identified and treated faster, said David Lubarsky, MD, MBA, vice chancellor of human health sciences and CEO at UC Davis Health. His organization is also rolling out an AI program that reads brain scans to rapidly identify the treatment needs of stroke patients and will help physicians at partner facilities decide which patients to transfer to UC Davis for lifesaving surgery to remove blood clots.

Zuckerberg San Francisco General has used AI to reverse disparities in the care of heart failure patients, Ehrlich said. In 2017 and 2018, the hospital realized that readmission rates were highest among Black men with substance use disorders and other social challenges, such as housing instability. The hospital developed strategies to support these patients, including establishing an outpatient clinic to treat both their heart failure and substance use problems. In partnership with UCSF, the hospital then used AI machine learning to scour the data of patients entering the hospital and quickly identify those eligible for the specialized care.

“We not only went from being the worst performer to the best performer in heart failure readmissions in the scope of a few years, but we reversed the disparity we saw,” Ehrlich said. “So Black/African American men actually did better than the general population.”

What Does It Take to Build Trust?

Building trust within the health workforce is paramount, Ghaly said. He pointed to recent protests by Kaiser nurses over the introduction of AI as a signal to health system leaders to do more to address worker concerns. A guiding principle should be that AI use empowers human capacity and doesn’t replace it, he said.

Successful AI implementation depends on the health care workforce, patients, and communities all trusting the technology, Reyes said. This requires leaders to engage the community every step of the way to make sure data are incorporated and interpreted correctly, to confirm that the technology is providing value, and to ensure that safety guidelines and definitions are universally understood, she said. Workers across the health care system need to be trained to confidently examine AI output and question when a result doesn’t look right, Reyes said.

To build trust, speakers highlighted the need for health care leaders to be transparent about how AI is used and what safeguards are in place. Lubarsky pointed to VALID AI, a collective of more than 50 health systems, health plans, and research partners that includes University of California health systems. Collective members are working together to identify uses, pitfalls, and best practices for Gen AI, including how to ensure safety and equity. Lubarsky said he believes the scale and collaborative nature of this effort will contribute to increasing trust in AI.

“As leaders, as policymakers, as people running systems in communities across California, we need to open the door to the conversation about how we’re using technology. Not to threaten jobs, but to strengthen,” Ghaly said. “It is possible for us to think together and collaboratively around where this goes and what the opportunities are.”

Carter said this early stage of AI development offers an opportunity to both support providers and improve patient outcomes. But it will require thoughtful risk reduction efforts, including making sure it is used responsibly, reaches communities equitably, addresses privacy concerns, and fully considers historic inequities, she said.

Authors & Contributors

Claudia Boyd-Barrett

Claudia Boyd-Barrett is a longtime journalist based in Southern California. She writes regularly about health and social inequities. Her stories have appeared in the Los Angeles Times, San Francisco Chronicle, San Diego Union-Tribune, and California Health Report, among others.

Boyd-Barrett is a two-time USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism fellow and a former Inter American Press Association fellow.

José Luis Villegas

José Luis Villegas is a freelance photojournalist based in Sacramento, California, where he does editorial and commercial work. He has coauthored three books on Latino/x baseball. His work appears in the Ken Burns documentary The 10th Inning and in the ¡Pleibol! exhibition that debuted at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History and has been appearing at museums around the country.

Villegas’s work has been exhibited at the Museum of Fine Arts-Houston; the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York; and at the Oakland Museum of California. Villegas also works as a medical photographer at Shriners Hospital in Sacramento.