What does it take for a doctor to see — really see — a patient well? That’s the question Alexa Miller, MA, set out to answer when she founded Arts Practica in 2011. Arts Practica is a medical education consultancy that leverages fine art to teach medical students and clinicians how to become better observers and diagnosticians. Miller, a painter, has been interested in improving health care quality ever since her sister was misdiagnosed with serious mental health conditions as a teenager. Because of those misdiagnoses, her sister was heavily medicated for many years, and it wasn’t until a state social worker and nurse correctly diagnosed her with Asperger’s syndrome that she received appropriate care and improved.

In 1998, the Yale School of Medicine became the first medical school to require an arts observation course to hone its students’ physical diagnosis skills. Other institutions, including Harvard Medical School, soon followed suit, and Miller began teaching in Harvard’s “Training the Eye: Improving the Art of Physical Diagnosis” program. Miller and her colleagues conducted a partially randomized controlled study of medical students and found that formal art observation training improved students’ observational acumen and diagnostic capabilities. Since then, she has consulted with Brigham and Women’s Hospital, the Boston University School of Medicine, and the American College of Physicians, among other institutions.

The COVID-19 pandemic has widened longstanding health disparities and shone a light on the health care system’s role in perpetuating racism through unequal access and treatment. I interviewed Miller to learn how the relationship between art and medicine can not only help doctors become better diagnosticians, but also address implicit biases that impede equitable care.

Q: Some people may be surprised or skeptical to learn that art can play an integral role in medical education. How can art observation training help health care providers perceive their patients differently and become better diagnosticians?

A: Diagnosis is the core of medicine, and the skill of observing is key to diagnostic accuracy. One way to learn to be a better observer is to engage in rich, interactive experiences with visual art, which exposes us to other worlds and worldviews. These experiences can simulate physicians’ encounters with patients who are very different from them, but in the galleries, the conditions are much less fraught than in the clinics or medical classrooms. Nobody is dying, and nobody is supposed to be an expert in the art we’re observing.

Visual arts training has been shown to improve observation and other skills central to diagnostic accuracy. It’s easy to believe that observations are objective, but when you start observing a work of art and then hear somebody else discuss that piece, it can be humbling to recognize how differently people see the same thing.

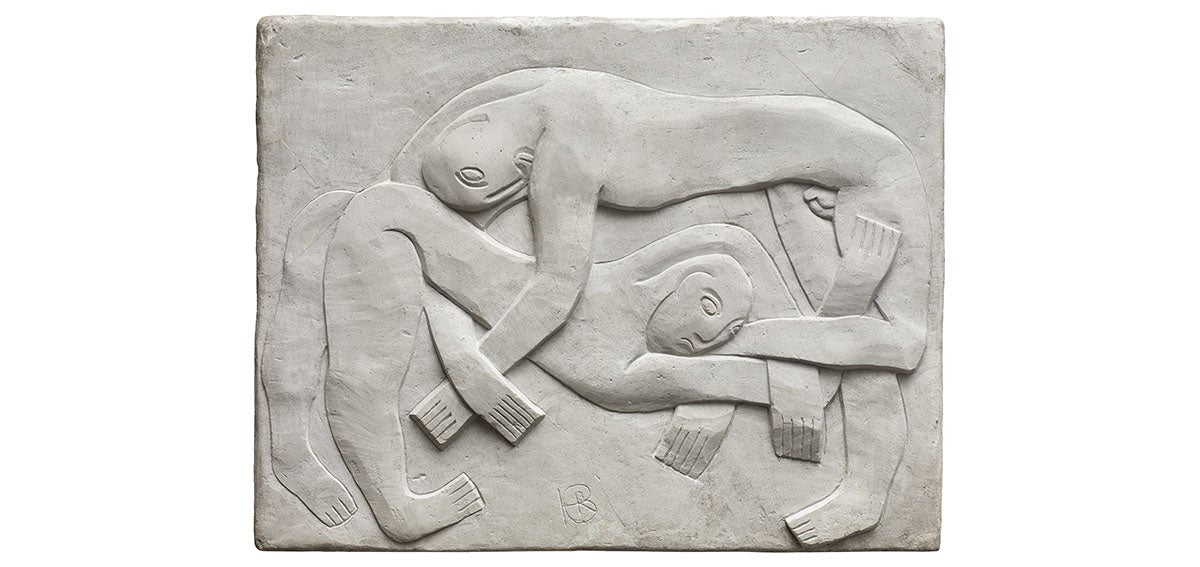

For example, I had a group look at this work of art without disclosing the title. We talked about all kinds of things — was this something from ancient Pompeii? Is it a Modernist expression? Is it a man and a woman? Is it possibly two men, or can we even know the genders at all? Are they involved in a fight or conflict, or is it actually very peaceful? Could it be lovemaking or are they perhaps sleeping?

I love using this work of art because you can see a lot of paradoxical things at once, but you might never see most of those things if I told you this is called The Wrestlers. Most likely, you would hear, “Oh, wrestlers. Okay, I’m done looking at it.” I like to select works of art that will engage people in the basic practices of observation and listening, and then awaken their self-awareness of the biases they carry.

Q: Do you think arts observation training can help clinicians combat racism or address their implicit biases?

A: Combating racism requires structural change and the transcendence of violence within systems. I see medical humanities as a part of the latter, and it can inform the former. Visual arts experiences can help us recognize the biases that shape what we see, and Yale has done some really pioneering work in this regard.

There has been research on the use of visual imagery to disable stereotypes. One study found that showing people “counterstereotypical” images or messages at least temporarily limited participants’ biases. Exposing people to other worldviews and culture through art is an early step in combating racism, although without follow-up and action it would remain part of the problem.

That said, the art interventions that you choose are important. Art museums are not neutral spaces. Most art museums come from basic colonial impulses, and many collections contain mostly the art of white men.

Going back to the issue of errors of judgment, a lot of that has to do with clinician bias and a failure to recognize bias. Errors happen when judgment is clouded by preconceived information or by emotions, most notably fear, that arise when we encounter somebody who is different from us.

A really great diagnostician might have a gut reaction or intuition about what is going on with a patient, but they put checks in place to ensure they look at things in other ways. So, for example, that means not assuming a patient is always late to an appointment because he or she is overweight and lazy, and instead digging in to realize the patient lives in a neighborhood where there is no grocery store, there is no direct transportation to the clinic, and he or she had to take three buses to get there.

Q: Your sister had such a poor experience with the health care system. How has her pain informed your work and your thinking about perception in the world of medicine?

A: Arts Practica has increasingly focused on uncertainty in medicine and how it is approached and discussed in clinical settings. I’m passionate about this issue because things can go very well or people can get hurt in moments of uncertainty. I’ve spent a lot of time with patient safety researchers and people who are deeply concerned about medical misdiagnosis, which — even before COVID-19 — was the third leading killer in the US. That’s cancer first, heart disease second, poor medical judgment third. (COVID-19 became the third leading cause of death starting the week of March 30.)

When you look at many cases in medicine that have gone horribly wrong, you find that the root cause is that somebody made a bad call because they did not handle uncertainty well. In the face of uncertainty, instead of slowing down, checking their biases, or checking in with a colleague, they avoid or overlook the uncertainty and proceed. It’s heartbreaking that most of these errors are made by people who want to do right by their patients and who chose medicine because they are committed to their patients. Health care providers are in a very tough spot because of industry pressure to move quickly and see high volumes of patients each day.

“At the end of the day, being able to recognize and accept uncertainty is a first step in being able to manage it better and avoid misdiagnoses.”

Q: Has the coronavirus pandemic changed the way physicians handle uncertainty in their clinical lives?

A: We are still learning about the virus, and it is expressed in the body in so many ways. What I have been hearing from clinicians is that the heightened focus on COVID-19 has the potential to derail other diagnoses. But a silver lining of the COVID-19 pandemic is that it has normalized conversations around uncertainty. It has shown that uncertainty is, by nature, a part of clinical encounters. It is something to talk about and not something to fear. At the end of the day, being able to recognize and accept uncertainty is a first step in being able to manage it better and avoid misdiagnoses.

Q: What lessons from this pandemic and the recent demonstrations against racial injustice can medical schools apply to improving the health care system as a whole?

A: I think that the most important thing medical schools can do is to recruit cadres of future doctors who represent our racially diverse population. There have been many studies over many years that reveal the impact of bias and racism on medicine. A pretty glaring study about newborn care just came out. It shows that Black newborn babies are three times more likely than White newborns to die under the care of White doctors. That disparity drops significantly when the doctor is Black. You just can’t look away from that, especially during a pandemic with such glaring racial health disparities.

Medical schools can also do a lot better to teach the phenotypes that accurately represent our population. Most didactic examples of disease and how they express are based on White male bodies, so a lot of misdiagnoses occur because students are not exposed to the wide range of ways in which diseases are expressed across genders and ethnicities.

It’s important to remember that medicine is itself an art. It’s very much based in the principles of science, and it’s also a social process. We need pro-social clinicians who understand structural racism and its impact on health. They need to better understand food insecurity, how zip codes impact health and the ability to access care, and the ways in which structural racism permeates the health care system.

We are in a time of reckoning and awakening. I believe the best thing we can do now is share a vision of a diverse human family that is able perform at its fullest potential. Sparking doctors’ ability to accurately see their patients is a consequential part of this picture.

Authors & Contributors