Dolly Lucio Sevier, MD, grew up so close to the US-Mexico border in Brownsville, Texas, that she had American classmates who lived in Mexico and commuted across the border daily for school. Brownsville is one of the poorest places in the country, with limited access to health care and healthy food.

After completing her pediatric residency at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Sevier felt a responsibility to return to her hometown, where she now finds herself on the front lines of the nation’s historic child migrant crisis.

Sevier told the Atlantic’s Jeremy Raff that her role as a pediatrician includes “being the voice for the kid, the advocate.” She never could have predicted that would include being an advocate for migrant children held in squalid conditions in a US Customs and Border Protection detention center known as Ursula.

In a medical declaration obtained by ABC News, Sevier wrote, “The conditions within which [the children] are held could be compared to torture facilities.”

More than 1,000 migrant children are being held in Ursula, a retrofitted warehouse in McAllen, Texas. A team of immigration lawyers — alarmed by what they saw during a recent visit — asked Sevier to visit the detention center and evaluate the young inmates. Children were being held in overcrowded facilities (PDF) with limited food, blankets made of Mylar sheets, and no access to showers.

After examining as many children as she could, Sevier found “evidence of sleep deprivation, dehydration, and malnutrition.” Most troubling, she witnessed unusual behavior that she attributed to psychological trauma. Most of the children Sevier sees in her pediatric clinic resist or cry when they are frightened. But the children she examined at Ursula were submissive — at first “totally fearful, but then entirely subdued.” She told Raff, “I can only explain it by trauma, because that is such unusual behavior.”

Pictures of Children’s Pain

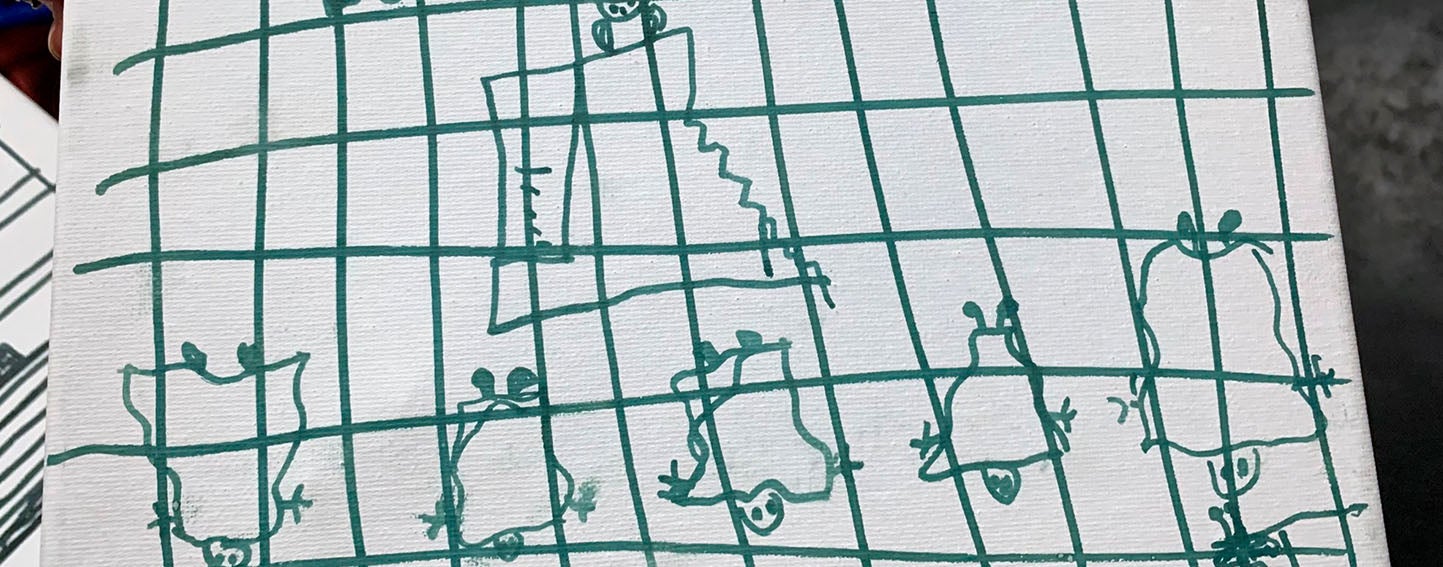

On July 3, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) released disturbing drawings made by migrant children after their release from detention. Time magazine reports that three drawings, “created by a 10-year-old Guatemalan boy, an 11-year-old Guatemalan child, and a third child identified only as 10 years old,” were sent to Sara Goza, MD, president-elect of the AAP, by a mental health clinician and social worker.

The children were asked to draw their experiences in Border Patrol detention centers like Ursula (the AAP does not know which detention centers these three children were held in). One drawing depicts five caged stick figures lying on the ground, covered by blankets. A guard wearing a hat watches from above, while two others stand at the exits.

“Migrant kids were living in isolated cellblock units, subject to pepper spray and other forms of force or discipline, and allowed outside only for limited periods of time. “

—Michelle Wiley, KQED

“The fact that the drawings are so realistic and horrific gives us a view into what these children have experienced,” Colleen Kraft, MD, immediate past president of the AAP, told CNN. “When a child draws this, it’s telling us that child felt like he or she was in jail.”

These troubling conditions are not limited to detention centers in Texas. KQED’s Michelle Wiley reports that immigration facilities across California are failing detained children with disabilities. Investigators with Disability Rights California, the nation’s largest disability rights group, in the past year visited nine California facilities run by the Office of Refugee Resettlement, which is responsible for housing unaccompanied migrant children in the US. They found that the agency fails to provide children with disabilities with necessary special education services, adequate health care services, and facilities appropriate for their mental health needs. “For example, migrant kids were living in isolated cellblock units, subject to pepper spray and other forms of force or discipline, and allowed outside only for limited periods of time,” Wiley writes. Many of the children have post-traumatic stress disorder, self-injurious behavior, suicidal ideation, or other mental health concerns.

Serious Threat to Long-Term Health

Reports about conditions at migrant detention centers have alarmed pediatricians and human rights advocates around the world. California Surgeon General Nadine Burke Harris, MD, MPH, an expert on childhood trauma, tweeted, “Traumatic events, like forcible separation from a parent, put children at risk for long-term health problems. . . . The harmful conditions documented in federal detention centers are a serious health threat that demands action.”

Michelle Bachelet, United Nations high commissioner for human rights, condemned the US for detaining children, saying that it “may constitute cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment that is prohibited by international law,” according to Vox. “Detaining a child even for short periods under good conditions can have a serious impact on their health and development — consider the damage being done every day by allowing this alarming situation to continue,” Bachelet said in a statement.

A systematic review of studies on the relationship between immigration detention and mental health found “profound and far-reaching mental health difficulties” among detained children and young people. The review, published in BMC Psychiatry, concluded that “detention should be viewed as a traumatic experience in and of itself.”

Additionally, the US policy of family separation subjects children to multiple types of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), according to a JAMA Viewpoint article written by the commissioner and chief of staff of the New York State Department of Health. Migrant children who are forcibly separated from their parents experience emotional neglect, parental separation, scenes of violence, and parental incarceration. And, while incarceration of children is not an official ACE, the authors argue that “simply being held in [detention] facilities may become an ACE for some” of the migrant children.

In an interview with the Greater Good Science Center at UC Berkeley, Burke Harris said that ACEs are “associated with changes in the structure and function of children’s developing brains, in their developing hormonal systems, and even in the way their DNA is read and transcribed.” A landmark study of more than 17,000 Kaiser Permanente members linked higher ACE scores with higher risk for poor health outcomes.

Time Is of the Essence

These studies strongly suggest that now is a critical time to mitigate the physical and mental harm suffered by migrant children in US detention centers. The authors of the BMC Psychiatry study stress the importance of minimizing the length of detention. Multiple studies have found a significant positive correlation between detention duration and negative mental health consequences. The AAP also tweeted that “no amount of detention is safe for a child.”

A study published in BMJ Pediatrics calls for the US and other countries that detain immigrant children to “reduce harm and promote the resilience and recovery of traumatized children by developing post-migration policies and processes.” Immigrant families must be reunited as quickly as possible, and children must be given access to trauma-informed health services, including culturally competent psychological and psychiatric support, the study concluded.

Some officials in Washington, DC, are paying attention to the studies. Congress has called Department of Homeland Security (DHS) officials to testify about the overcrowded conditions at detention centers. On July 12, the House Committee on Oversight and Reform heard from Jennifer L. Costello, the acting inspector general of DHS, about the “substantiated allegations of mistreatment” at detention centers. Kevin McAleenan, the acting secretary of DHS, has agreed to testify before the committee on July 18.

Sevier’s time at Ursula was spent working in a makeshift clinic as efficiently as she could, examining children one by one as they were brought in by Border Patrol agents. She examined 38 children on that day, taking meticulous notes such as “Underweight, fearful child in no acute distress. Only concern is severe trauma being suffered from being removed from primary caregiver.” She gave those notes to the immigration lawyers, who will use them to pressure the government to improve conditions in Texas detention centers.

The pediatrician told ABC News that the facility “felt worse than jail. . . . It just felt, you know, lawless. . . . I can’t imagine my child being there and not being broken.”

Authors & Contributors