James Hogan can’t remember a time when he lived without physical pain. The 81-year-old retired English professor grew up in the hills of Arkansas, too poor to seek medical help for numerous childhood injuries and illnesses. Now a San Diego resident, his childhood medical challenges are with him still — cumulative injuries that cause constant chronic pain in many parts of his body. For decades Hogan has been taking a combination of opioids even though they never completely freed him of pain. Instead they only helped keep him functional.

Figuring out where patients like Hogan fall on the spectrum of opioid users was a crucial first step for a San Diego medical group that is tackling the opioid epidemic. The strategy is to educate prescribers and patients so that longstanding medical practice patterns can be updated.

“When you look at the spectrum, there are those who get started on opioids, then they get dependent,” said Parag Agnihotri, MD, medical director of population health and post-acute care at Sharp Rees-Stealy Medical Centers in San Diego. “Or you can focus on the other end, on those who are completely dependent, but that involves a lot of support, so we decided to focus on new starts. If you can nip it in the bud, then you won’t have a problem.”

Agnihotri oversees data analytics at Sharp, which has more than 500 doctors, and he noticed that a high number of opioids were being prescribed there — and that physicians were burning out caring for patients seeking opioids from them. After he began looking into it three years ago, Sharp formed the safe opioid committee to put prescribing practices under the microscope. It includes Agnihotri, pain management and primary care physicians, a surgeon, a rehabilitation specialist, and a data analyst.

“The street value of opioids is very high, much more than regular morphine, which has very little street value,” Agnihotri said. “We’ve been prescribing it more and more, and there’s also a higher demand for it. Now we know we need to manage pain enough to get people to finish rehab, but not to the point of removing all pain, which might lead to adverse effects.”

The goal is to get patients to a functional level without overreaching to the point where it leads to adverse behavior.

Weaning Patients Off High-Dose Opioids

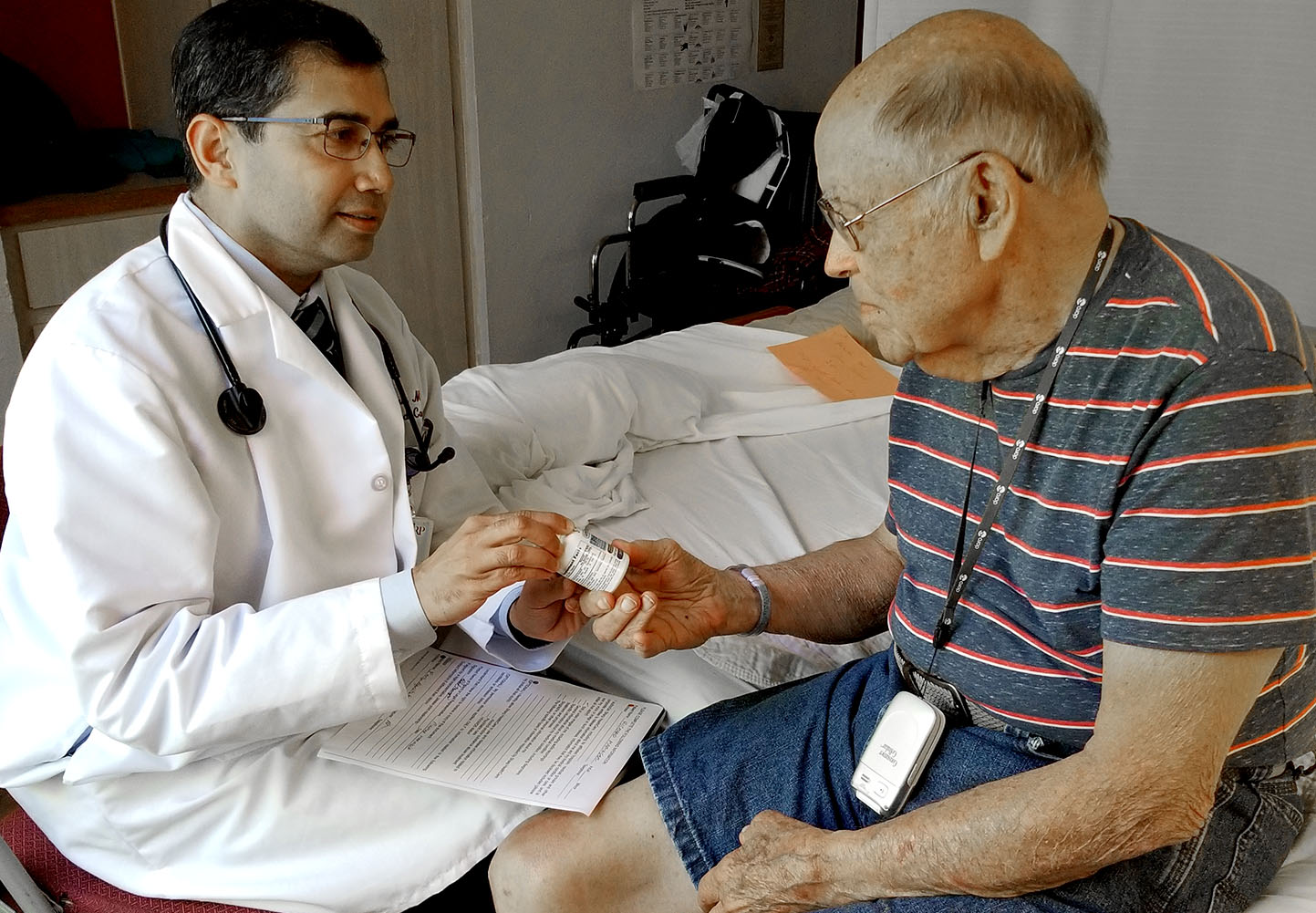

Over the years, Hogan tried many approaches, including an electronic spine stimulator and a daily cocktail of drugs that included up to five pills of hydrocodone, four of morphine, and some gabapentin. On a recent morning at a Sharp Rees-Stealy office in San Diego, a nurse asked Hogan to rate his pain on a scale of 1 to 10. He rated it at a 4.

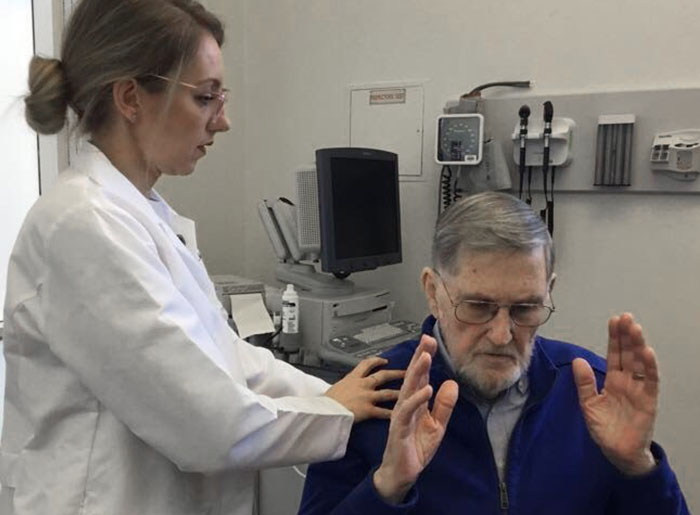

Hogan was there to see Bianca Tribuzio, MD, a physical medicine and rehabilitation specialist, or physiatrist, who serves on the Sharp safe opioid committee with Agnihotri. When Hogan came to Tribuzio two years ago, she was the first medical professional in all his years of seeking help for pain who asked him if he would consider alternatives to his drug regimen. Although he was 79 at the time, he agreed because he was tired of living with pain.

He enrolled in Sharp’s pain management program, a six-week course that helps patients understand their chronic pain and tackle it with meditation, guided imagery, stretching, and other stress reduction techniques. As they learn coping techniques from experienced physical therapists and others, patients are monitored by sensors. It wasn’t easy, but Hogan tapered his use of the drug cocktail and learned other ways to ease his pain. He is now down to two 10-milligram morphine pills a day. Is he an anomaly, or can patients with chronic pain and opioid dependency wean themselves off it?

“He is, and he isn’t,” Tribuzio said. “A lot of patients are realizing these medications may not be that safe, that people are dying from overdoses, and that they don’t control long-term pain. We do have patients asking about alternatives, so part of it is patient-driven, but a lot of it is prescriber-driven. We tell people when it’s needed and when it’s not right for them, and patients are also more open now to other options.”

While California has fared better than some states, it remains in the grip of the national opioid crisis. The California Opioid Overdose Surveillance Dashboard shows that in 2017 the state had 1,882 opioid overdose deaths, 8,376 visits to the emergency room for overdose of opioids (including heroin), and close to 22 million opioid prescriptions dispensed.

Tools and Training to Rethink Prescribing Practices

Agnihotri says his participation in the CHCF Health Care Leadership Program from 2010 to 2012 taught him it was essential to create smart objectives with measurable, applicable goals for reducing opioid prescriptions. “The rigorous CHCF fellowship helped put the opioid crisis in context,” he said. “It helped to build the skills necessary toward building a data-driven patient-centered program. Having the ability to call in one of the [program’s] alumni was very helpful in sharing and collaborating around best practices toward reducing the burden of the opioid crisis.”

Join the CHCF Health Care Leadership Program

This two-year, part-time program is for clinically trained health professionals in California, including behavioral health providers, nurses, dentists, and pharmacists, with at least five years of leadership experience. Led by national experts in workforce and leadership development at Healthforce Center at UCSF, the program addresses health care issues from the perspectives of business management and public policy. Applications are open April through June each year.

Collaboration is key, he said. In addition to colleagues within Sharp, Agnihotri is collaborating with outside experts in San Diego. One of them is Roneet Lev, MD, an emergency physician at Scripps Mercy Hospital who chairs the prescription drug abuse medical task force for the San Diego County Medical Society. “She is the chief champion for San Diego’s pain coalition,” he said.

The Sharp committee set out to reduce inappropriate use of opioids by 10%, reduce the overall morphine milligram equivalent (MME, or total daily opioid dosage), prevent overdoses, increase the use of naloxone (a rescue drug that immediately reverses opioid overdoses), and expand the use of holistic pain management.

To achieve this, the committee deployed a multi-pronged strategy, starting with educating prescribers and patients and targeting outreach to high-volume opioid prescribers. The group worked on safe tapering of opioids in patients whose pain symptoms didn’t improve. It taught physicians how to use the MME calculation created by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) as a guide to understanding when dosage levels required careful watching and when they were so high that they heightened the risk of overdose.

The committee also embedded an assessment tool in the patient’s electronic health record (EHR) that referenced personal and family history of drug and alcohol abuse. It provided early access to naloxone and enabled pharmacists to prescribe it. Finally, it promoted the use of California’s prescription drug monitoring database, the Controlled Substance Utilization Review and Evaluation System, or CURES. CURES allows prescribers to check if the patient has already received a similar prescription, when it occurred, and who picked it up.

“For dealing with the repeat offenders who keep asking for pain medicines, the secret sauce is CURES,” Agnihotri said. “We were able to get all the prescribing history from the health plans, which pay for the medication. We showed it to our prescribers to see how the same prescription was used in a couple other pharmacies too. So CURES has been instrumental in tackling prescribing patterns.”

New Mindset Leads to Success Curbing Opioid Use

As a result, Sharp saw an 11.5% drop in prescriptions for opioids from 2015 to 2016 and a 24% reduction in new prescriptions. The number of high-dose prescriptions also declined by 24%.

People already living with addiction require a lot of resources to reverse habits, but there are successful examples like Hogan. New starts sometimes do need opioids, Tribuzio pointed out, but there are non-opioid measures they can try first, from therapy to heat to massage. It pays to follow the CDC’s recommendation, “start low and go slow.”

To reduce inappropriate opioid use, the committee used three approaches. First, providers are taught when to prescribe it, when not to, and what non-opioid options patients have, such as yoga or stress management for lower back pain. Second, the committee used transparency to bring peer pressure to prescribing patterns. “If my colleague in the same zip-code has a lower prescribing pattern, it motivates me,” Agnihotri said.

Third, it focused on consumer education, creating handouts physicians can use to teach patients about pain management, and how to handle pushback from patients who insist on obtaining opioids or object to tapering high doses. The committee also removed certain drugs from its EHR prescribing module, including Opana (an oxymorphone narcotic) and Soma (a carisoprodol muscle relaxant; not an opioid but dangerous when combined with one). The US Food and Drug Administration warned that these drugs were being badly misused, so the only way it could be prescribed at Sharp was if it was written up manually, but that’s almost impossible to do because policy requires every opioid prescription be recorded in the EHR.

Collectively, these strategies have begun making an impact, Agnihotri said. But there is still a long road ahead. When patients come to physicians in pain, it’s often hard for them to resist the instinct to prescribe painkillers. But that’s where the tools and guidelines can help.

“When patients are on high-dose opioids, and we want to reduce it, we think patients will object,” he said. “So the CDC has given us a safe opioid tapering handout on how to do it. The MME calculation has been very helpful. If your patient is above 50 MME, you better be careful. If your patient is above 90 MME, then you should keep this person under watch, since they could overdose on it. As a provider, I use an app and put in the numbers for any patient, and it alerts me if it’s at or over 90. So there’s a flag, like a GPS warning.”

Authors & Contributors

Padma Nagappan

Padma Nagappan is a journalist who covers health, environment, and agriculture. Within the health beat, she focuses on public health issues, health impacts of environmental issues, medical advances, and medical research. She has reported on substance abuse and the opioid crisis, health disparities, cancer, mental health, and drug interactions. Her stories have been published in media outlets in the US and UK, including Everyday Health, Dermatology Times, US News & World Report, New Scientist, TakePart, MedShadow, Ag Alert, SugarOnline, San Diego Union-Tribune, and KPBS TV and Radio.

Padma earned a master’s degree in business administration from Madurai Kamaraj University in India.