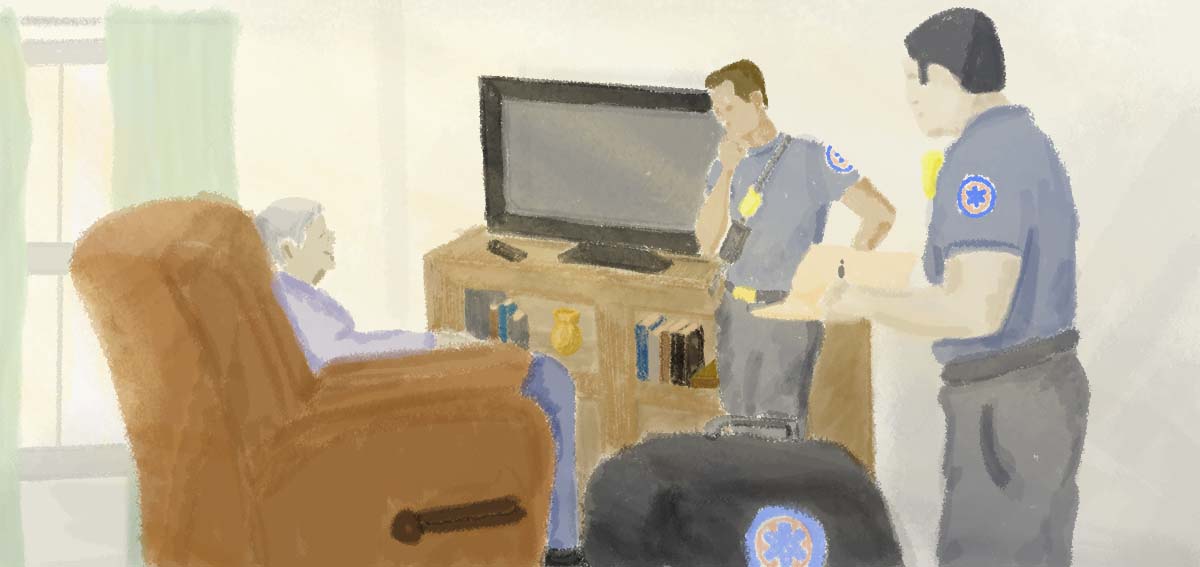

A 61-year-old woman is discharged from the hospital after suffering a respiratory emergency. Her case is referred by the physician to a community paramedic to provide follow up at the woman’s home. Over a few weeks, the paramedic checks in with the patient several times, ensuring that her vital signs remain stable, verifying that she was able to obtain and control her medications, and assisting in managing a foot infection. The paramedic helps the client arrange to see an array of physicians and accompanies her on one visit where the paramedic clarified the challenges that affected her ability to provide self-care at home. At the final home visit, the woman’s baseline health status was significantly improved, and she was following all her doctors’ orders.

Sound futuristic? This care was provided in 2017 by a community paramedic working in one of the California community-based projects that have expanded the role of these medical professionals to better meet local health care needs. Begun as pilots, the projects have enhanced patient outcomes and demonstrated the potential to save significant health care dollars.

The idea of community paramedics is not new. Modern emergency medical services (EMS) have their roots in helping people in their neighborhoods and communities. One of the earliest EMS programs, Freedom House, began in 1967 in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where a local physician trained the first American paramedics to provide street-level care in poor and disadvantaged neighborhoods. Over the decades, paramedics have become commonplace throughout the country. With the historical focus on providing prompt emergency care, paramedics typically receive nearly 2,000 hours of intensive education and training in patient management, which includes extensive study in anatomy and physiology, pathophysiology, and pharmacology. Paramedic education programs are accredited through the same process as many other allied health professions. Paramedic students can choose to complete their training with a certificate or with an associate degree in paramedicine.

Providing Care to All Who Call

In a Central Valley home, a young man is experiencing a psychiatric crisis. Concerned for his safety, his parent calls 911 for help. Ordinarily, a police officer would respond to such a call, after which a paramedic ambulance would transport the patient to a hospital emergency department where few psychiatric resources are available. Instead, community paramedics evaluate the patient, determine there was no medical need for hospital care, and transport the patient to a behavioral crisis center for further psychiatric evaluation and targeted treatment.

Scripted television programs portray paramedics as members of a heart-pumping, adrenalin-filled profession responding to calls to help people caught up in shootings, car crashes, and cardiac arrests. Patients are saved on every show and are grateful for the paramedic services they received. While paramedics certainly do all those things, their role is far greater. EMS professionals are the backbone of the health care safety net in the US. Paramedics provide care and comfort to anyone who activates the EMS system, without regard to where they live, their income, or their immigration status. Most emergency calls for service involve a complex weave of medical, socioeconomic, and psychological issues that require time and attention to resolve.

Unfortunately, our health care system remains fragmented and not equally accessible to all. Numerous studies point to health inequities related to race and socioeconomic status. Patients transported by paramedics to emergency departments often arrive with conditions exacerbated either by the absence of helpful resources or by lack of access to or by limited availability of existing resources. In the example above, home health care providers are overwhelmed with their existing workloads and are especially challenged to connect with patients within the first 48 hours after hospital discharge, when patients are most vulnerable to setbacks. Many of these patients return to the EMS system again and again, straining emergency departments and depleting scarce resources needed for true emergencies.

Community Paramedics Provide Effective Care That Really Helps

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) was designed to reform the health care system with expanded eligibility for coverage, reduced out-of-pocket costs for health plan consumers with lower incomes, and coverage with essential benefits that include no- or low-cost preventive care. A key principle of the ACA is the so-called “triple aim” framework developed by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, which determined that health care managers should:

- Improve overall patient care, quality, and satisfaction

- Enhance the health of populations

- Reduce per capita health care costs

Recognizing that the spiraling cost of health care was not translating to better patient outcomes and that a well-trained workforce was available to provide more effective care in the community, the California EMS Authority launched the California Paramedicine Pilot Project in 2014. The objective was to evaluate the feasibility of paramedics expanding their roles beyond emergency response. In all, 53 California cities received a variety of nontraditional services from community paramedics, including hospice support, postdischarge care, direct observation of daily tuberculosis treatment, and transportation to alternative nonemergency sites such as sobering centers, urgent care centers, and psychiatric facilities. The Healthforce Center at UCSF analyzed the project and concluded that community paramedics collaborated effectively with numerous health care partners, provided services safely and efficiently, reduced medically unnecessary transports to hospital emergency departments, and saved more than $3 million during a short time span.

Stepping Up to Help in a Public Health Crisis

It is the spring of 2020. Paramedics and emergency medical technicians are standing under tents on an unusually warm spring day. Vehicles occupied by anxious people are lined up around the block, inching toward the tents. There, the car window is rolled down and a paramedic swabs the nose of the driver. Testing for the coronavirus is in full swing. Over the next several months, paramedics test many thousands of people at multiple locations across the state. Meanwhile, in other parts of California, staff members in skilled nursing facilities are overwhelmed with the virus. Teams of paramedics and emergency medical technicians are deployed to those homes for weeks, working alongside the reduced staffs to care for residents.

As the state pilot project was demonstrating that community paramedicine represented a valuable addition to California’s health care workforce, the health care system response to the COVID-19 pandemic unexpectedly reinforced that message. Besides transporting gravely ill patients to emergency departments, paramedics staffed numerous testing sites throughout the state and provided direct care to long-term care facilities, either supplementing or replacing staff infected by the coronavirus. As vaccines became available, paramedics pivoted to vaccinate hundreds of thousands of citizens throughout the state. Working relationships between public health and EMS got stronger, and what was essentially an experiment in real time demonstrated the effectiveness of innovative paramedic services.

Community Paramedicine Legislation

After considering the effectiveness of the pilot project, the California legislature enacted the Community Paramedicine and Triage to Alternate Destination Act (AB 1544) to authorize local EMS agencies to develop community paramedicine and alternative transport destination efforts. Regulatory guidelines for these efforts are to be developed by the EMS Authority. Signed by Governor Gavin Newsom in September 2020, this legislation significantly improves the way health care resources are managed by California paramedics, wherever patient encounters occur. The legislation allowed for the transition of existing pilot projects to program status, and local EMS agencies can formulate new programs customized to meet their community’s needs. Further development is predicated on the full promulgation of regulatory requirements related to AB 1544. There is urgency in completing this critical step because the bill is scheduled to sunset in 2024.

The legislation establishes enhanced education and training requirements for future community paramedics that will focus on health care equity issues. With their experience working “in the streets,” community paramedics will work closely with local physicians, nurses, behavioral health specialists, nutritionists, and others to broaden the network of care and services used to help their patients. This approach is designed to customize each community paramedicine program to accomplish the unique local goals developed by the community itself. Each program will provide the right services to the right people at the right time.

Continuing Opportunity to Do More

While the legislation goes a long way, it does not unleash all the potential of community paramedicine. The pilot project and many larger-scale programs throughout the nation demonstrated clinical and financial success with short-term, home-based follow-up care for people recently discharged from a hospital, to reduce readmission rates and to enhance patient self-management. Nonetheless, such care was excluded from the legislation and will not be permitted in California.

Critics of the pilot project argued that paramedics were not adequately trained to assess all chronically ill patients, such as those experiencing congestive heart failure. The evidence suggests otherwise.

Readmission rates were lower among patients visited by paramedics than for those who were not, saving money for both the patient and the hospitals, which are financially penalized when people become inpatients again within 30 days of discharge. This limitation will keep community paramedics from providing all the help they can provide. The UCSF analysis concluded that no patients were harmed by any interventions performed by community paramedics, including those in postdischarge care plans.

Over six decades, paramedics have evolved from ambulance drivers to sophisticated providers of intensive emergency health care. The time has come for these highly productive sources of care in the field to be more fully integrated into California’s overall health care and public health spheres. The result will be higher quality care and improved community health at reduced cost to taxpayers and payers. That is what the triple aim is all about.

Authors & Contributors

Jane Smith

Jane Smith, MA, EMT-P, has been in emergency medical services since 1983. She has worked in both the public and private sectors in roles related to public health, community colleges, nonprofit organizations, and the fire service. Since officially retiring, she has been volunteering with CARESTAR Foundation, the California Paramedic Foundation, and the California Community Paramedicine Advisory Committee.

Art Hsieh

Art Hsieh, MA, NRP, has been in the emergency medical services profession since 1982 and has worked as a volunteer, line medic, educator, and chief officer in private, third service, and fire-based EMS. He has directed both primary and EMS continuing education programs and currently is the paramedic program director at the Public Safety Training Center at Santa Rosa Junior College. A textbook author and editorial columnist who has presented at conferences across the US and internationally, Art is a past president of the National Association of EMS Educators and a scholarship recipient of the American Society of Association Executives.