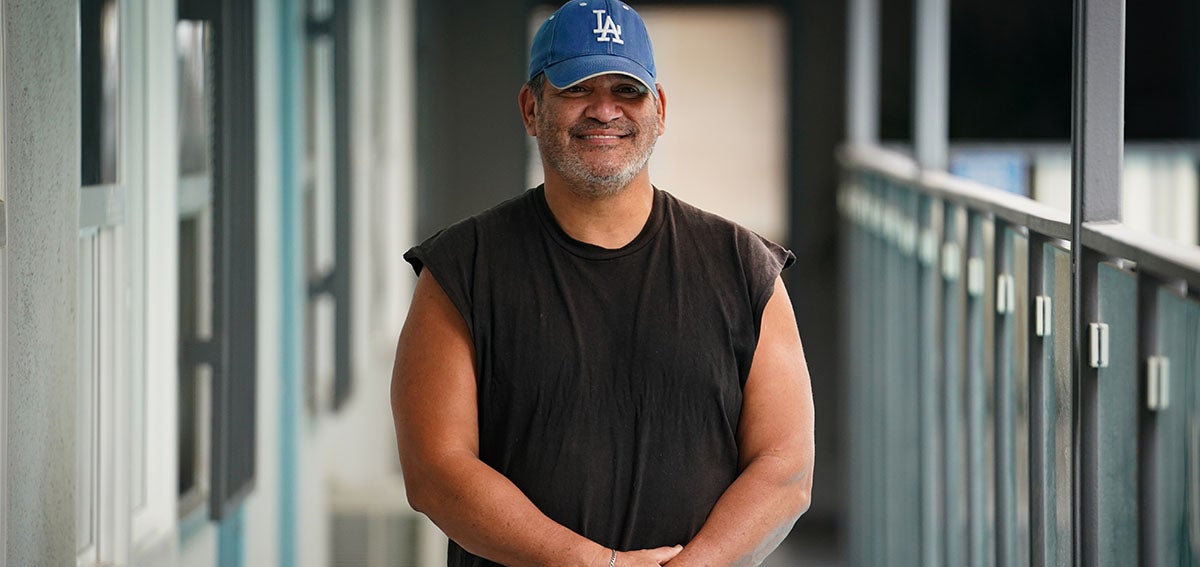

On a recent morning, Refugio Lopez, 58, limped into a room at Orchid, the transitional housing facility in Hollywood where he lives, looking to see a medical provider. With a knee injury and other health problems stemming from diabetes, walking just over a mile to the nearest low-cost community health center — Saban Community Clinic’s Hollywood Health Center — would be painful and probably impossible, Lopez said. Another option, calling his insurance provider or the clinic to arrange a free ride, “is a hassle,” he said.

Luckily for Lopez and about 39 other formerly unhoused people who now reside at Orchid, the clinic comes to them about twice a month.

“You don’t have to go anywhere, they’re right here,” said Lopez. “They help me with everything. It’s a blessing.”

Saban’s roving medical team is a three-person operation staffed by Physician Assistant Samantha Kumpf, Medical Assistant Jeffrey Figueroa, and Patient Navigator Amairany Alcala Reveles. Each month, the team visits 13 transitional and permanent supportive housing sites in Los Angeles and the West Hollywood area. They offer a wide range of free medical services, including general checkups, cancer screenings, vaccinations, chronic disease management, screening and treatment for sexually transmitted diseases, wound care, and mental health and substance use treatment. For specialty care and procedures that can’t be performed on-site, they make referrals. Alcala Reveles helps patients choose health insurance plans, assists them with enrollment, and organizes transportation to outside appointments. A Saban dental team alternates with the medical team to visit the housing sites as well as two clinic sites to provide regular oral health care.

Since Saban began sending teams to Orchid in 2021, they’ve helped Lopez sign up for health insurance through L.A. Care Health Plan, prescribed medication to control his high blood pressure and blood sugar, and helped him get a walker and dentures. The care has made him feel a lot better and more hopeful, he said.

“When I was homeless, I didn’t take care of myself,” Lopez said. “In the streets I knew how to survive, how to get food, a hygiene kit, blankets, and all that, but I was just surviving. . . . Now I can take care of myself.”

The idea to create the mobile medical and dental teams grew out of a pilot initiative Saban launched at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. At the time, the Federally Qualified Health Center was one of 16 Los Angeles-based health care organizations sharing $2.3 million in grant funds from a project called Health Pathways Expansion, developed by the United Way of Greater Los Angeles. The grant allowed Saban and other providers to bring primary medical care — and in some cases behavioral health and substance use treatment — to people staying at state-funded Project Roomkey hotels. The hotels were set up as temporary shelters for unhoused people during the first two years of the pandemic in an effort to protect them from exposure to COVID-19.

When the Health Pathways Expansion grant commenced, health care providers rarely offered medical care directly to people at shelters or transitional housing sites, said Eric Ares, who was then the homeless initiatives senior manager at United Way. While all the grantees had previously served people experiencing homelessness, they did that mostly within their own brick-and-mortar clinics. A few, including Saban, also had mobile teams bringing medical care to people living in encampments on the streets of Los Angeles.

Opportunity for New Partnerships

Some providers had been visiting shelters, but when Project Roomkey moved thousands of unhoused people indoors, the need became clear for a large-scale operation to bring medical care to this vulnerable population, Ares said. The grant also offered an opportunity for health care providers to foster new partnerships with the homeless service providers managing shelters and housing programs.

The Health Pathways grant concluded in June 2021. Instead of ending mobile visits to shelters, Saban expanded its program. The clinic’s grant-funded work at four Project Roomkey hotels proved that bringing medical care to people where they lived was a needed and viable option, said Arnali Ray, who served as Saban’s chief of strategy during the grant period. That need was expected to continue as Project Roomkey patients moved on to transitional and permanent housing under California’s separate Project Homekey initiative.

“We were able to identify needs, gauge the cadence of on-site presence, and most importantly, provide compassionate care by meeting them at their homes,” Ray explained in an email. “In addition, we were able to create and cultivate new partnerships with different homeless service providers that led to expanding the number of sites.”

Saban officials raised money through private donors to support continuation of the work. By June 2022, they had raised almost $2 million — enough to continue offering mobile medical and dental services for five more years. They also purchased a van and outfitted it as a mobile dental/medical clinic with equipment, such as an electrocardiogram machine for heart screening and a centrifuge to process blood tests. Previously, clinic staff members lugged equipment in backpacks from site to site, which limited how many procedures they could perform. The van also features a private clinic area for conducting sensitive exams, such as pelvic and cervical cancer screenings.

“Not having to coordinate, remind, and sometimes accompany residents to the doctor gives case managers more time to assist clients with other needs, such as securing income benefits and employment, and building social skills.“

Under the Health Pathways grant, Saban built partnerships with three organizations managing shelters and supportive housing: People Assisting the Homeless, LA Family Housing, and Aviva’s Wallace House. After adding a fourth partner, Weingart Center, the mobile clinic now serves 13 sites with about 850 residents.

Other former grantees said they had developed new partnerships as a result of the Health Pathways Expansion grant. Kathy Proctor, clinic administrator at Northeast Valley Health Corporation, said her organization now works more closely with homeless service providers in their area, and strengthened connections with the county’s health agencies during the pandemic. Evonne Biggs, a program manager at Venice Family Clinic, said her organization provides medical services at St. Margaret’s Center, a drop-in center in the Inglewood area of Los Angeles that is run by Catholic Charities.

Meanwhile, LA Christian Health Centers, which serves the massive Skid Row community of more than 8,000 unhoused people near downtown Los Angeles, developed new relationships with other homeless service providers. One of them is the Salvation Army, which regularly parks its outreach van outside the organization’s flagship New Joshua House clinic, said Shannon Fernando, the chief innovations officer for the Christian Health Centers.

“One of the big gifts of COVID-19 was all the connection and networking we had to make to really provide the safety net” for people experiencing homelessness, Fernando said.

Mobile care in general has taken off more broadly in Los Angeles, and Los Angeles County recently launched a fleet of mobile medical clinics to provide primary and urgent care at homeless encampments.

A Day in the ‘Roving’ Office

Many of the patients seen by Saban’s roving medical team have multiple health problems after years of exposure to substandard living conditions and insufficient medical care. These patients, often skittish about interacting with medical providers because of negative experiences and stigma, would likely not seek care at a clinic. By showing up regularly where formerly unhoused people live, Kumpf and her team can develop positive relationships with hard-to-reach patients.

“We have to build a lot of trust and rapport,” Kumpf said. “Sometimes when we encounter people, we might say ‘Hi’ to them the first 10 times before they’re actually ready to engage with us.”

The team saw a steady stream of patients on the morning they visited Orchid. Because the van was undergoing repairs, they set up their equipment in an empty room. One woman came in with a shoulder injury; another needed a flu shot and a COVID-19 booster. Karrie Feagin, another patient, just wanted to talk and showed the team pictures of her new cat. Kumpf noted the woman was due for a mammogram and asked Alcala Reveles to schedule her for an appointment and a ride to the screening center.

When Lopez was called, a checkup revealed that he had put on five pounds since the last visit and that his blood pressure was high. Some gentle questioning revealed he’d forgotten to take his medication and had been eating mostly pancakes. Kumpf urged him to set reminders on his phone to take his pills and scheduled him for a consultation with a nutritionist. Down the hall in her office, Diane McManus-Stovall, a case manager at Orchid, said the mobile visits make a “massive difference” for residents and staff. Not having to coordinate, remind, and sometimes accompany residents to the doctor gives case managers more time to assist clients with other needs, such as securing income benefits and employment, and building social skills.

“Taking the medical side away helps us a great deal,” she said. “It’s needed. It’s really needed.”

Even so, not all residents are taking advantage of the on-site visits, McManus-Stovall said. She and other case managers post the clinic’s schedule throughout the building and talk to residents to encourage them to go. She expects more will seek care over time as they see that the providers are consistent and trustworthy.

At the end of Lopez’s visit with Kumpf, the physician’s assistant gave him a short pep talk. She reminded him of the progress he’d made since he started coming to the mobile clinic several months before. He had lost weight and brought his blood pressure and blood glucose under control.

“You’ve done it before,” Kumpf told him. “We know you’ve got this.”

Lopez lifted himself up with his walker and headed back to his apartment to take his medicines.

Authors & Contributors

Claudia Boyd-Barrett

Claudia Boyd-Barrett is a longtime journalist based in Southern California. She writes regularly about health and social inequities. Her stories have appeared in the Los Angeles Times, San Francisco Chronicle, San Diego Union-Tribune, and California Health Report, among others.

Boyd-Barrett is a two-time USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism fellow and a former Inter American Press Association fellow.

Harrison Hill

Harrison Hill is a documentary photographer and filmmaker based in Los Angeles, California. His work focuses on social justice issues centered around communities of color in the US.