From her bright, second-floor office at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital and Trauma Center (ZSFG), Susan Patricia Ehrlich, MD, MPP, oversees a mini-city within California’s most densely populated urban center.

The soft-spoken, athletic CEO draws on an impressive reservoir of stamina to tackle her grueling job at the 146-year-old public hospital, where she is in charge of a staff and faculty of 5,400, a budget of $1.1 billion, and a community of mostly patients with low incomes who receive 24/7 state-of-the-art medical care. ZSFG is the only trauma center for San Francisco and northern San Mateo County, and the only area hospital offering round-the-clock emergency psychiatric service.

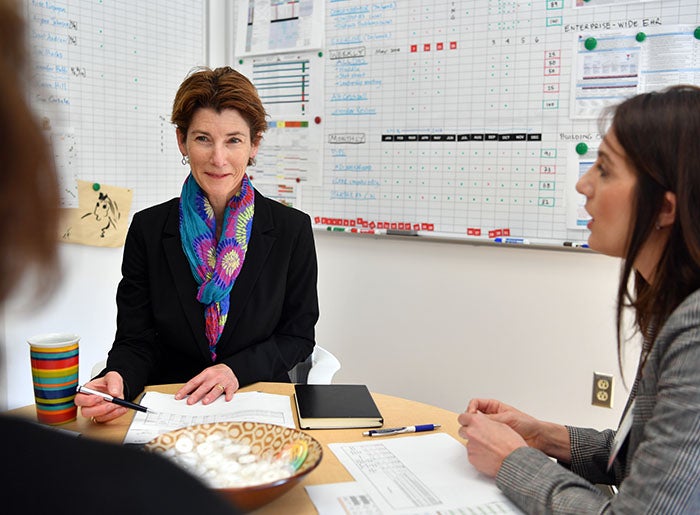

Yet for all the challenges, Ehrlich can see her way clear the minute she enters her office each day. There, in blue, red, and black marker pen on a whiteboard wall, are the words “2018 Strategic Initiatives.’’ In orderly fashion, months are divided into weeks, weeks into days, and days into time slots for huddling with department managers and others to study stat sheets and to review calendars, progress reports, and “difficult problems.’’

This whiteboard is the critical road map that Ehrlich and her colleagues rely on at the 400-bed safety-net hospital, a tool she learned about more than a decade ago as a physician and later as CEO at San Mateo Medical Center.

Looming Threat to Hospital Finances

The tool will guide her during an uncertain health care future. The Affordable Care Act (ACA), the landmark health care overhaul approved by President Barack Obama, sharply expanded California’s Medicaid program, Medi-Cal, almost doubling the hospital’s revenues. Adversaries of the ACA have shown little interest in ending their eight-year effort to invalidate the law.

In April 2018, Ehrlich, 58, marked her second anniversary as ZSFG’s CEO. “Having the opportunity to lead ZSFG is one of the greatest privileges of my career,’’ Ehrlich said. “I work with the most talented team on the planet, serving my community and helping to improve the health and lives of the most vulnerable among us.”

As a candidate for the CEO job, it helped that she was already an evangelist for an innovative organizational management system called “Lean philosophy.”

“One of the really important reasons I was chosen for this job is because of my practice with Lean philosophy, and the California Health Care Foundation (CHCF) [and its efforts to promote Lean] was a key part of how I became a devotee of it,” she said.

Originally used to help transform Toyota, Lean philosophy and tools are used by many public hospitals in the US to cope with uneven resources and create more value for patients.

Embracing the Lean Philosophy

“To some, the focus is on quality, ensuring things get done, and removing waste from the process,’’ Ehrlich said. “To me, it’s more about supporting people and developing people into leaders.’’

Which is exactly what occurred in her own career. Ehrlich’s introduction to Lean happened years after joining San Mateo Medical Center in 2002 as a staff physician. That’s where the center’s then-CEO and medical director, Sang-ick Chang, MD, MPH, recognized her potential to move up the ladder.

“She shone with intelligence, integrity, and vision,’’ he said. “She was the full package.’’

A few years later, Chang recommended she apply for a spot in CHCF’s Health Care Leadership Program, which cultivates management skills in clinicians through a special curriculum and a real-world project. She was accepted to the 2005–2007 fellowship class, and continued her rise through the hospital’s clinical and administrative ranks.

Passing the Torch

By early 2009, Chang — himself a graduate of the CHCF leadership program — had moved on to a new position. Ehrlich succeeded him as CEO.

After the foundation sponsored a program for safety-net hospitals to determine how they might use Lean, she began to embrace the concept. That was followed in 2011 by a CHCF grant that enabled leaders from five California public hospitals, including San Mateo Medical Center, to learn more about Lean tools from public hospitals using them in Washington, Colorado, and Wisconsin.

Lean management philosophy was certainly a long way from her days as codirector of the North Carolina Student Rural Health Coalition, where she was a leading advocated for farm workers’ health.

“I had no idea what I was doing,’’ Ehrlich recalled. “None whatsoever. I thought being a leader was being appointed a leader, and that you had authority, and people would do what you wanted them to do.’’

“When I saw leaders at the Department of Public Health who were practicing physicians, who also did administrative and policy work, that to me seemed like an extremely fulfilling career.”

—Susan Ehrlich

But over the years, she learned much more about life, medicine, and managing teams.

It didn’t hurt that Ehrlich was raised in a family of health care role models. Her grandfather was a general practitioner in Minnesota. Her late father, S. Paul Ehrlich, MD, MPH, had wide-ranging medical training and a background in public health. He served as acting US Surgeon General under President Richard M. Nixon and later as US representative to the World Health Organization.

“My dad was a great inspiration for me,” said Ehrlich. “He was an amazing man.’’ Her mother, Geraldine McKenna Ehrlich, who spent years working in health care contract management, gave her daughter an understanding of the nuts and bolts of the business.

“Health care and public service — that has been my life,” said Ehrlich. “I’ve never done anything else.’’

Chang attributes Ehrlich’s success to her hard work, her being a quick study, and her grace under pressure. Insights she gained from her parents’ professional lives helped too, he said.

Essential Leadership Traits

“It’s very hard to acquire that level of organizational intelligence from just your working life,’’ said Chang, now assistant dean for clinical affairs at Stanford University Medical School. “It’s challenging for many physicians when they enter leadership positions because they don’t have 20 years of experience learning how to manage conflict, and people, and how to communicate effectively in the way you would if you were the manager of a restaurant starting at age 22. Physicians often never learn until suddenly it’s thrust upon them later in life.’’

Ehrlich’s professional journey started at Duke University, where she earned a bachelor’s degree in public policy, followed by a master’s degree in that field from UC Berkeley. She worked as a health budget specialist with the California State Legislative Analyst’s Office. Later she was appointed budget and planning director for the San Francisco Department of Public Health, where she realized she should follow a new career direction that would sustain her professionally and emotionally.

“When I saw leaders at the Department of Public Health who were practicing physicians, who also did administrative and policy work, that to me seemed like an extremely fulfilling career,’’ she recalled.

To the surprise of many who knew Ehrlich, who was then in her early 30s, she applied to medical school.

“I told my parents I was quitting my job and I was going to start my undergraduate classes in chemistry and physics and then apply to medical school,’’ Ehrlich said. “They thought I was nuts. . . . They tried to talk me out of it and asked: ‘Do you know what you are doing? How this will impact the rest of your life? Are you sure you want to do this?’’’

Confidence to Change Direction

Ehrlich had never been more certain. She completed medical school at UC San Francisco and then completed a residency in internal medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. Her circuitous career path delayed some aspects of her life — she was older when she married and when she and her wife, Jill Linwood, had their two children, now 10 and 13 years old.

Join the CHCF Health Care Leadership Program

This two-year, part-time program is for clinically trained health professionals in California, including behavioral health providers, nurses, dentists, and pharmacists, with at least five years of leadership experience. Led by national experts in workforce and leadership development at Healthforce Center at UCSF, the program addresses health care issues from the perspectives of business management and public policy. Applications are open April through June each year.

“On balance, I’ve been very lucky,’’ she said.

That good fortune continued when she finished her residency and began working with Chang. That led to her CHCF fellowship, her introduction to Lean, and the Lean leadership program adopted by five California public hospitals.

“It permeates everything we do,’’ said Ehrlich. Every year hospital leaders from every corner of ZSFG use Lean tools, metrics, and the philosophy of value-based leadership to solve issues and evaluate their progress.

Data-Driven Rigor

“It’s very rigorous and data-driven,’’ said Ehrlich. Hundreds of workers at ZSFG have been trained in the technique, which she believes has resulted in better care for patients.

For example, last year, the group reviewed safety statistics in four areas where staff were concerned about harm to patients: falls, surgical site infections, catheters associated with urinary tract infections, and hospital-acquired ulcers linked to bed sores and other pressure wounds. Staff then set a goal to reduce the number of infections by 25% and met their target, Ehrlich said.

“She looks at people’s talents and the way our minds see things, and then she helps guide and direct us,” said ZSFG’s chief nursing officer, registered nurse Terry Dentoni. “She is the conductor. We all have our sheets of music, and she makes it flow.’’

Ehrlich is also wrestling with another challenge: managing the number of patients who are too frail to be discharged without being diverted to skilled nursing facilities or other supervised settings. The high cost of housing in San Francisco has limited the resources available to these patients, many of whom are homeless, Ehrlich said. So the ZSFG Lean team has come up with a solution by creating a ”social consult service” to help move these patients more quickly to other appropriate settings.

The 70-Hour Week

“This job is vast,’’ said Ehrlich. Her day usually begins at 5:00 AM with a quick run to keep fit and relieve the stress of the typical 70-hour work week. Arriving at work by 7:00 AM, she tries to make it home for dinner as often as possible.

“It’s really a 24/7 job — at any moment, anything can and does happen here because we are the only trauma hospital and 24/7 psychiatric emergency service for San Francisco,’’ she said.

As she copes with ceaseless deadlines, budget pressures, management challenges, and the hectic pace of managing the hospital, Ehrlich strives to lead by example, said Dentoni.

“She is calm, and she is thoughtful,’’ said the veteran nurse. “She commands respect, and her authority is well-established.’’

At the same time, Ehrlich must also contend with things she can’t control, including the fate of the ACA under a Republican-controlled Congress and a shifting Supreme Court.

Connected to Humankind

“We went through the long period of Congress wanting to repeal and replace, which would have hugely impacted this organization and the community,’’ she said. Because the ACA has allowed more people to enroll in Medicaid, safety-net hospitals have been able to increase their revenue.

Still, the Trump administration’s crackdown on immigrants continues to exert a chilling effect on patients who need medical care but fear deportation.

ZSFG and its affiliated clinics continue to support and treat these patients, said Ehrlich, who keeps her medical practice fresh by seeing patients for a half-day each week.

“It connects me to humankind, to the work we do here,’’ she reflected. “And it supports me emotionally. I was trained to be a doctor because I wanted to be doctoring.’’

It also helps her better understand how the hospital is providing care, to whom, and how it can improve. “I feel like the luckiest person in the world because I am doing everything I want to do,” said Ehrlich. “I’m taking care of patients, running a mission-driven, inclusive organization, and being involved in state and federal health care policy. I just love that.”

Authors & Contributors

Tracy Seipel

Tracy Seipel is a freelance writer living in the San Francisco Bay Area. She is a former editor and reporter for the San Jose Mercury News and the Bay Area News Group.