Listening to Californians with Low Incomes

Between 2019 and 2021, CHCF funded a major research project to better understand the health care experiences, needs, and values of Californians with low incomes, including understanding changes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Learn what we learned by listening to Californians with low incomes.

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought mental health issues to the forefront of our lives. While almost everyone has experienced the stress, loss, and grief that this historic event has wrought, these impacts have not been distributed equally across all groups. A new CHCF report, Listening to Californians with Low Incomes: How They Experience the Health Care System and What It Means for the Future, looked at the health experiences of people during the pandemic and found higher reported levels of mental health pain and suffering among Californians with low incomes than among people with greater wealth. While the underlying trends that emerge from this report are not new, they have been exacerbated by the public health crisis.

Even before COVID-19 swept the globe, Californians with low incomes reported higher levels of depression, stress, and emotional problems than people in higher income brackets. The pandemic aggravated feelings of anxiety and mental unwellness. The research shows that mental health concerns were the main reason people sought help from health care providers during the study period. Nearly all respondents with low incomes (96%) experienced at least one type of COVID-19-related stress, and many endured multiple types of stress.

The report is based on a survey of California residents and follow-up interviews with respondents as part of a two-year research project conducted by NORC at the University of Chicago. In qualitative interviews, the researchers gathered stories from respondents about heightened stress and mental health issues during the pandemic.

Loneliness and Separation

“It’s not just regular stress — it starts to deviate into mental health stress,” a 24-year-old Latinx resident of California’s Central Coast told NORC. “For the portion of the population that I am included in that does have mental health issues already, it’s a double whammy. And to be separated and have loneliness and have that feed into the mental health disease that’s already there, just waiting to be fed.”

The research findings come at a time when major new mental health initiatives and increased funding are emerging from the Biden administration and also are being proposed in Sacramento. The American Rescue Plan, enacted in March, will provide some $3 billion in mental health aid to states. California is slated to receive $187 million from the federal government to strengthen community mental health services and treatment for people with severe mental health conditions and $206 million to expand services for people with substance use disorders.

(Article continues below.)

A System in Need of Overhaul

For decades, mental health needs and services have been ignored and devalued by health systems and planners. One silver lining of the pandemic is that it showed that the system needs radical overhaul to be responsive to the mental health needs of Californians — especially those with low incomes and communities of color. Here are some key recommendations from Listening to Californians with Low Incomes: How They Experience the Health Care System and What It Means for the Future:

- Telehealth will play an important role in better serving mental health needs. As in-person service models are brought back, investment in telehealth and hybrid models of care are needed. Throughout the pandemic, telehealth was a vital lifeline to care and largely well received by patients with low incomes. Telehealth can go a long way toward making mental health services available in languages other than English. Patients should have equal access to telehealth and in-person care and be able to choose based on their preferences and needs.

- Invest in addressing the social determinants of health. Ensuring safe and secure housing, food security, and employment will be critical to reducing inequities in mental and physical health. Reaching these goals requires a transformation in how health care and other social services are structured, financed, and delivered.

- Accelerate the integration of mental health services into primary care. Redesign services to reach people where they are (instead of waiting for them to engage with the system) and to promote mental well-being and prevention.

- Expand and diversify the mental health workforce to better meet the needs of people from different cultural backgrounds. The behavioral health workforce is too small and far too lacking in diversity to serve all the Californians who need help. In addition to training more counselors, social workers, nurses, and psychologists, the state needs a bigger community-based workforce to assist people experiencing mental health issues. This would include community health workers, promotores de salud, and peer counselors. “Instead of ensuring that people come to the health care system, it’s how do we get the health care system to the people?” said Rishi Manchanda, MPH, president and CEO of HealthBegins. “The payment and financing structures that we have right now make that impossible for many — even for the most social-mission-oriented organizations.”

California governor Gavin Newsom, in budget proposals released in May, proposes to spend $4 billion to improve behavioral health services for children and youth up to age 25 by investing in technology, increasing mental health and substance use services for youth, strengthening school-based prevention and counseling services, and expanding the behavioral health workforce for young people, among other measures. He also proposed $1.6 billion for CalAIM, or California Advancing and Innovating Medi-Cal, a multiyear process led by the California Department of Health Care Services to improve the health outcomes and quality of life experienced by Medi-Cal patients, especially through coordination of services for people with complex needs.

The NORC report’s findings also underscore the need to improve mental health services and outcomes in California, said Carlina Hansen, the CHCF senior program officer who spearheaded the research project.

“The mental health of Californians with low incomes is under acute strain, as are the systems that serve them,” Hansen said. “We have an opportunity to use this crisis to learn to respond in new ways and creatively reach people where they are.”

Structural Barriers to Behavioral Health

Here are key findings from the report:

More than two-thirds of people with low incomes who wanted to see a doctor or other health professional during the pandemic did so to get help with a mental health problem. Of those who described their prepandemic mental health as “fair” or “poor,” 53% said it worsened as the crisis wore on. A significant segment of people with low incomes who wanted mental health care — 42% — did not receive it.

These findings reflect what many clinicians and experts have observed during the pandemic: While the efforts to provide mental health services to people in need were extensive and unprecedented, those initiatives were sometimes frustrated by structural barriers built into the system and by the sheer volume of need.

One of those barriers is the lack of integration between the general health care system and the systems that provide services to people with mental health and/or substance use disorders.

“Health systems are the leading and most egregious perpetuator of structural stigma because of the way that they’ve created silos and continue to treat mental health as its own isolated thing,” Dr. Benjamin F. Miller, a psychologist and chief strategy officer of the Well Being Trust — a national nonprofit focused on transforming the health system — told NORC researchers. “This reinforces the false dichotomy that mental health isn’t foundational to your health. So the key here is integration.”

No Lull in Demand

Some newer models of care did help to break down barriers. School-based health centers managed by UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital Oakland and located in two Oakland public high schools provided a source of vital help for adolescents and families with low incomes.

“We were already in a mental health crisis with high mental health needs before the pandemic, with suicide rates on the rise,” Saun-Toy Trotter, a family therapist who manages the UCSF program, told me. “And we definitely have had an overwhelming number of referrals. We’ve been full all year long; there’s no lull.”

Therapists on Trotter’s team frequently were at full capacity and had to scramble to make referrals and get assistance from other programs. In many cases, they would learn from a teacher or student about broader social needs, such as a family running short of food or a parent needing mental health support. “I saw a lot of people addressing mental health in many different ways, not only through therapy, but also making sure they had hot spots and laptops and food and all of those different things,” Trotter said.

“The biggest factor in providing effective care during the pandemic has been telehealth and being able to use both telephone and video conferencing.”

—Christina Grabowsky Viani, Sanctuary Centers

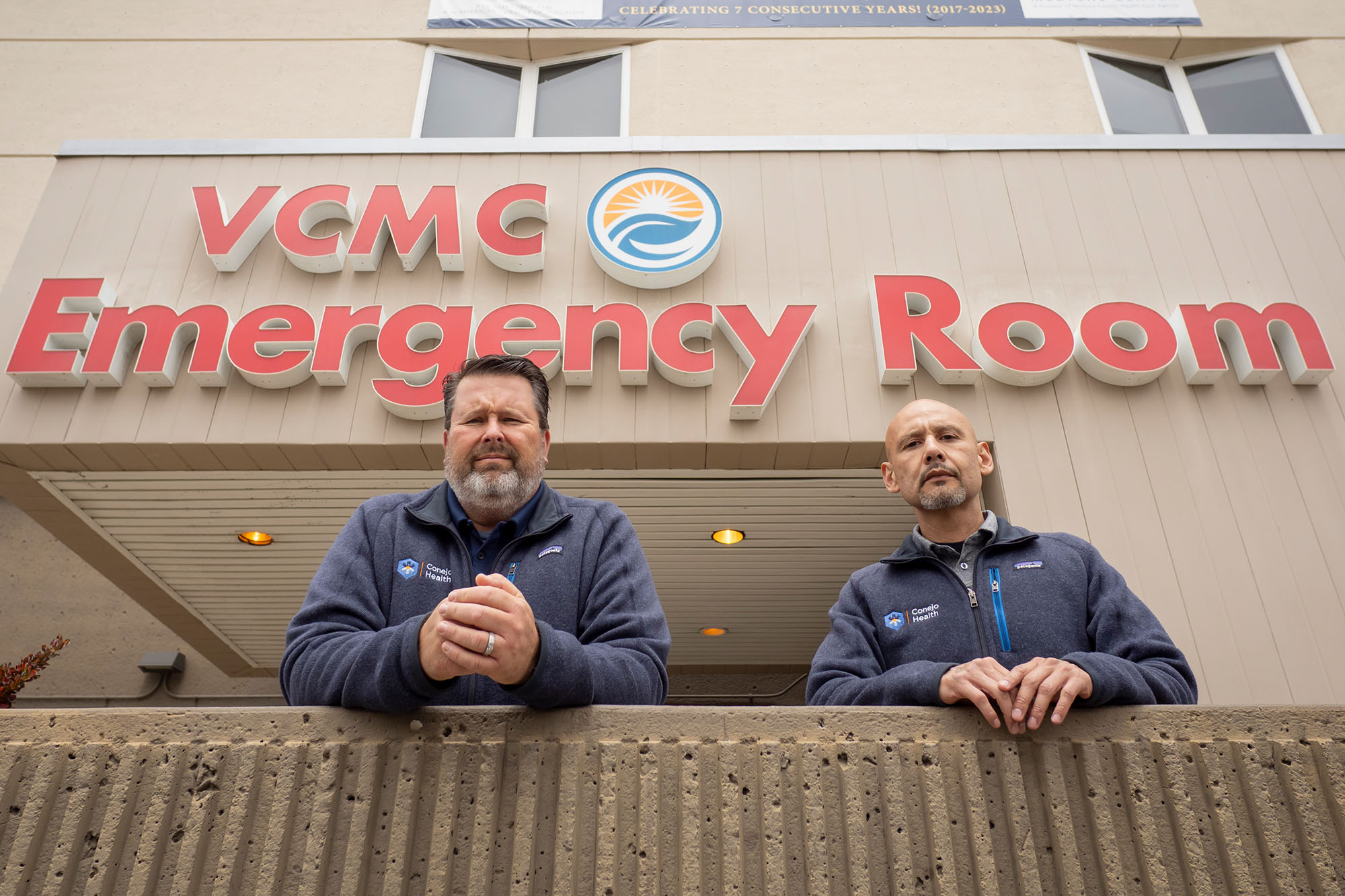

Other mental health providers across the state report being inundated and often feeling overwhelmed by the volume of people seeking help and the intensity of their need. Christina Grabowsky Viani, assistant clinical director of Sanctuary Centers, a nonprofit mental health agency in Santa Barbara, told me two groups of her agency’s clients have been affected, in different ways.

Before the pandemic, most patients with low incomes who had mental health needs — but no issues with substance use — were managing, with support, to function pretty well, Grabowsky Viani told me. “The pandemic really tipped that over,” she said. “A lot of these clients started experiencing stresses at home, as well as in the community, and that amplified their mental health issues.”

A second group of people who grapple with both substance use and co-occurring mental health problems were hit even harder. Some, on probation and being served by case managers or probation officers, lost access to the resources that helped them navigate their lives. “Suddenly, courts and probation shut down, and they didn’t have a structure that was helping them,” said Grabowsky Viani.

Some were experiencing homelessness or became so when the pandemic put a stop to their “couch surfing” — staying as an overnight guest at the homes of friends and relatives. These clients became difficult to track and to connect with. They could no longer go to a cafe to charge a phone or connect to the internet. Getting medications also became harder, Grabowsky Viani said. Without reliable phone or internet access, “clients could not shift to telehealth to meet with their psychiatrists, and it became very difficult for them to get their medications refilled.”

Success with Telehealth

Generally, though, the broader use of telehealth services enabled by federal rule changes was a major success. Two-thirds of people with low incomes who received care during the pandemic did so via telehealth, NORC found, and 70% of these patients would likely choose a telehealth visit in the future.

“The biggest factor in providing effective care during the pandemic has been telehealth and being able to use both telephone and video conferencing,” said Grabowsky Viani. Many clients of Sanctuary Center’s mental health programs are now opting for a hybrid model of care, doing midweek check-ins or treatment reviews by telephone and then coming in person for group sessions.

“Before, we were saying, ‘You have to come in,’ and our clients were working, babysitting, or had other appointments,” she said. “We would lose the chance to support them midweek. But now we can say, ‘You’ve got a busy day, let’s talk on the phone, we’ll regroup. I’ll see you in group again in three days.’ If we could keep that [arrangement] for the long term, it would fortify our wraparound supports for our clients.”

Authors & Contributors

Rob Waters

Rob Waters is an award-winning health and science writer whose articles have appeared in BusinessWeek, Mother Jones, Stat, San Francisco magazine, the San Francisco Chronicle Sunday magazine, the Los Angeles Times, and many other publications. He is the founding editor of MindSite, a digital publication covering mental health news scheduled to launch in fall 2021.