|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready…

|

Building a health care workforce that reflects California’s demographic diversity is no small task in a state facing significant physician shortages and vast health disparities by race and zip code. In Los Angeles, the historically Black college Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science (CDU) is answering the call to educate future physicians from underrepresented communities, having recently welcomed 60 students to the inaugural class of its newly independent medical school.

Students are making history, too, in receiving their medical education from the only independent four-year medical degree program offered through a historically Black institution west of the Mississippi River. That dearth of Black medical schools is a legacy of slavery, White supremacy, and racist educational reforms in the early twentieth century that resulted in the closing of all but two institutions. Only in the 1970s did two more Black medical schools open, including CDU, and no others have opened since. And yet, studies show that when the racial or ethnic background of the physician workforce mirrors that of the population being served, patients experience better health outcomes.

Founded in the wake of the 1965 Watts Revolt, CDU has always envisioned being home to a medical school and creating a world without racial disparities in health and health care. But racism and financial challenges have blocked the university from creating a fully-independent medical school until now. Prior to this school year, CDU medical students were educated through a program run jointly with UCLA. In 2021, however, a critical boost toward independence came when the California legislature set aside $50 million to support the new CDU program.

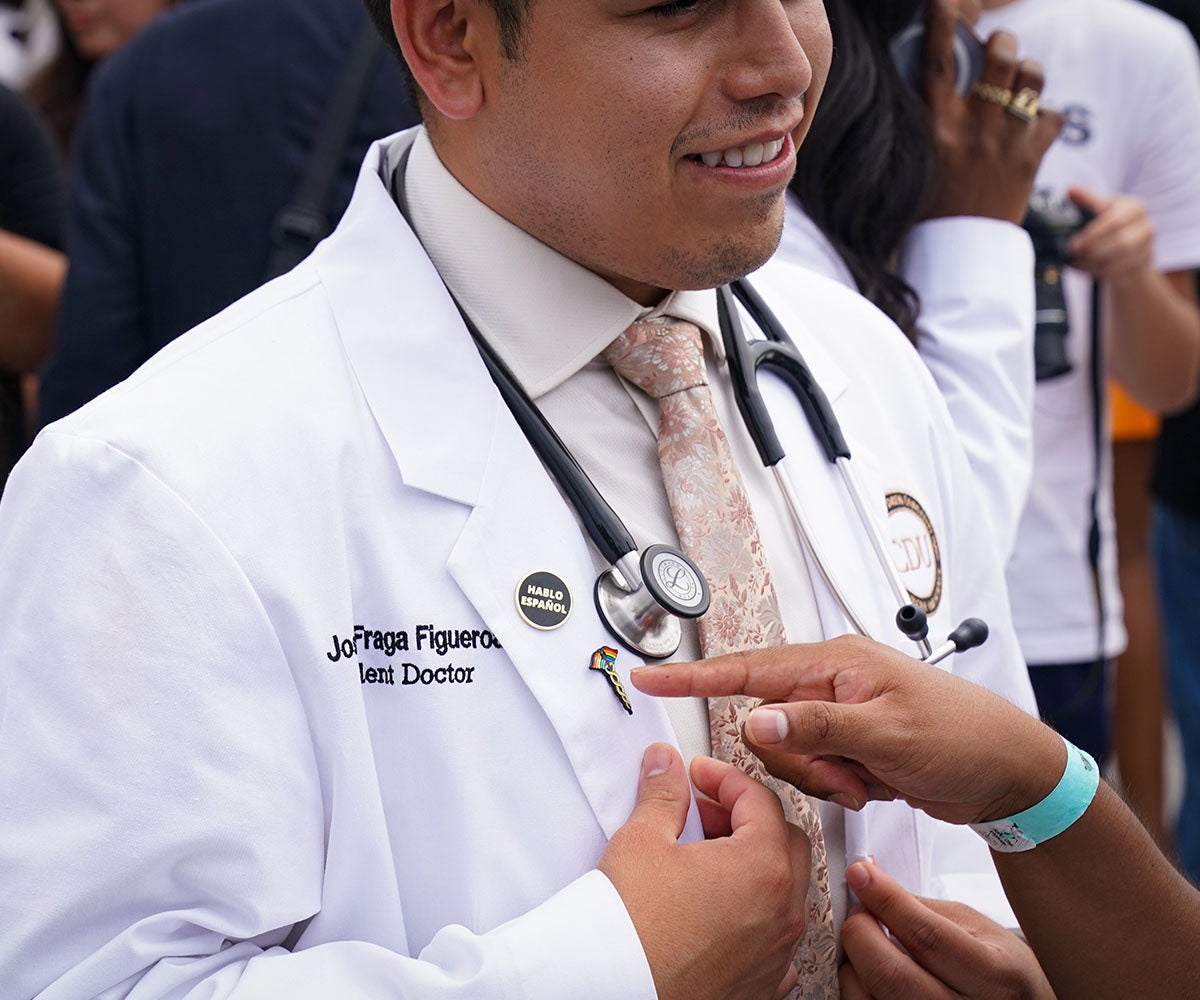

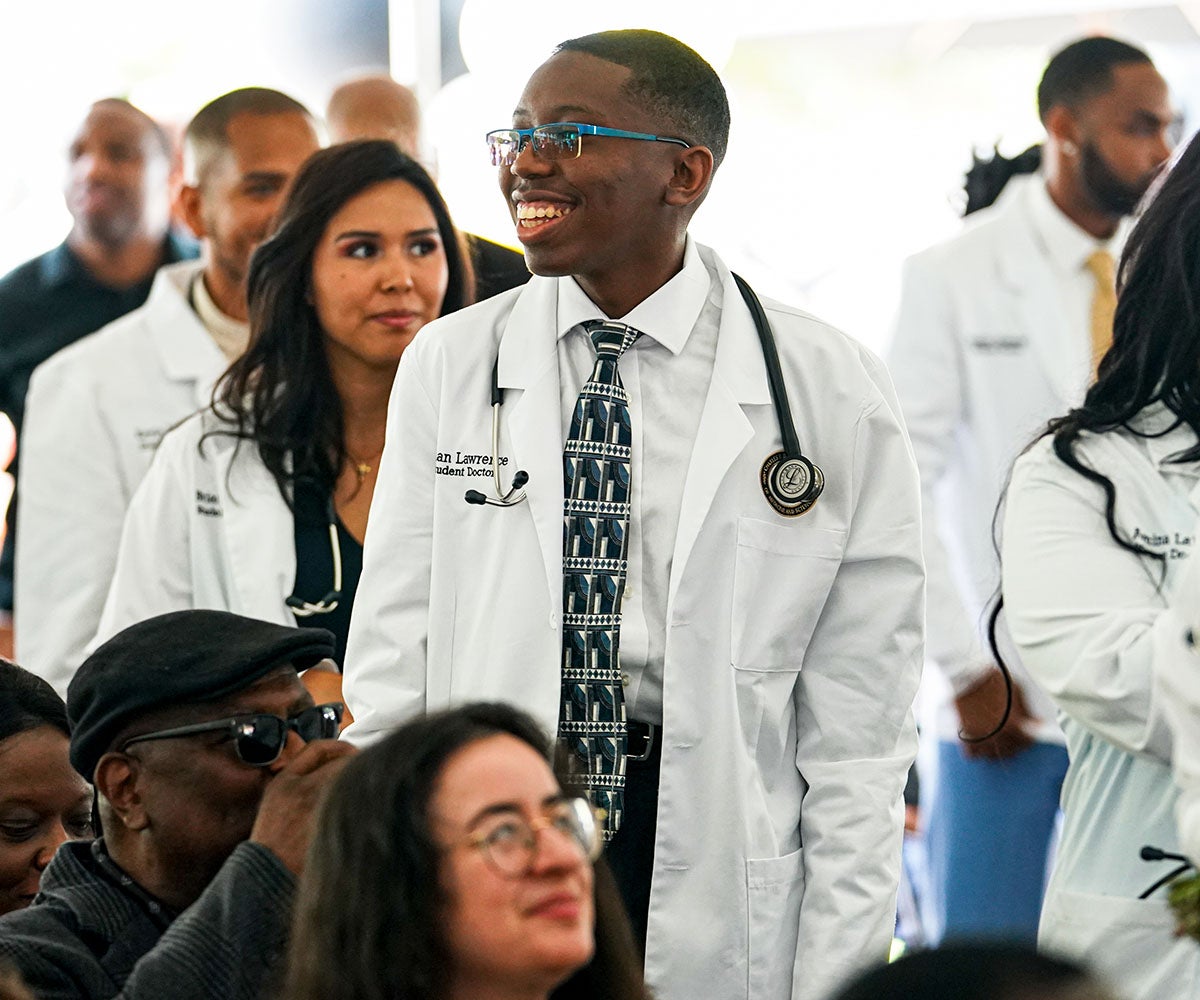

On August 19, 2023, the university held a white coat ceremony for its inaugural medical school class, which includes 36 female and 24 male students. Approximately half of the cohort is Black, and one quarter is Latino/x. What’s more, a majority of the cohort is proficient in languages other than English, including Spanish, Arabic, and American Sign Language.

After the ceremony, I spoke with Regina Stokes Offodile, MD, associate dean of student affairs, and Margarita Loeza, MD, assistant dean of student affairs and admissions. I asked them about the significance of this class – and about their students’ pathways to post-graduate medical residencies at nearby Martin Luther King Jr. Community Hospital, the Watts/Willowbrook area’s only full-service hospital.

Q: What was it like to see the university’s first cohort of medical students receive their white coats?

Offodile: It was a full-circle moment for me. I was on a waitlist in 1994 to get into Charles Drew, and I left Ohio State to go through the Charles Drew-UCLA combined medical education program. It was different from what we have today. After coming to Charles Drew, becoming an associate dean, and helping develop the medical school program that is solely the university’s — an exclusive Charles Drew experience and product — it was very emotional for me to watch these students receive their white coats. I felt like a proud mama. I felt like we are part of a legacy that we are creating. And to be in the vanguard of it — it just gives you chills.

Loeza: I think it was historic, especially in the planning of the white coat ceremony itself. I thought a lot about how I had been to many other white coat ceremonies where faculty put the coats on students. But we decided to let the family members put the coats on students and let them have an unlimited number of family members attend, which is how we ended up with over 1,000 people at the ceremony. This was important because it was like their families were giving the students to us to care for and guide our community. And we want it to be normalized that you don’t have to be a doctor to put a white coat on a future med student.

Q: What are some of the unique characteristics of this cohort?

Loeza: Many are the first in their families to attend college. They are recipients of Pell Grants, which is assistance based on financial need, as well as participants in the Association of American Medical Colleges Fee Assistance Program, which helps students who would not be able to apply to medical school without financial assistance. Many of them are bilingual and trilingual. Many religions and countries are represented, and they’re from all over California. They are the face of California. They look like the people who use Martin Luther King Jr. Community Hospital, which is right across the street from the university.

Offodile: As Dr. Loeza has shared, they look like the world. Yes, they live here and they’re from LA, from other parts of California, and from a few other states, but their roots and their families definitely represent a global perspective.

Q: Why is having a diverse health care workforce important, and how does it affect a patient’s health?

Offodile: When someone comes to see a physician and the physician looks like them, speaks their language, and perhaps wears the same kind of cultural clothing, it empowers people to understand their health care with their doctor. It lets them understand that having good health care and access to care is a collaboration. It means having someone who can look through the same lens the patient is looking through and understand and appreciate the patient’s perspective. I think those kinds of things are extremely important. It doesn’t mean that a doctor must come from another country, or a doctor must grow up in poverty, but it does give the patient and the doctor who may have those shared experiences common ground to begin a collaboration.

Loeza: I just think about the COVID-19 pandemic. I looked at the numbers every day in Los Angeles County, and it was the poor and the people of color dying first. Unfortunately, it will happen again. We need to find solutions for pandemics and other health care disparities, and those solutions will be found by having doctors who come from our communities. These students have already experienced health inequities and disparities in their families and for themselves, and I think they know the solutions.

Q: How did Charles R. Drew University approach the admissions process for this inaugural class?

Loeza: I’ve been working in admissions for many, many years, volunteering at different medical schools and working with a pipeline program called MiMentor that I co-founded. I’m also a member of Latinx Physicians of California and the National Hispanic Medical Association, and my colleagues and I talk about the challenges of low representation. I heard similar things while I was seeing patients over the years in Los Angeles. I saw Black patients who were frustrated with the medical racism they had faced and had a hard time finding a Black doctor. Patients who would ask for a Spanish-speaking doctor had to wait a long time to see me. Women who wanted a female doctor also had long waits.

I kept waiting for many years. It’s like, when are the doctors we need coming? I started thinking about the workforce we need to take care of the Medi-Cal population. I was thinking about language, sex, and understanding poverty. I was thinking about being resilient, being resourceful, being diligent, being caring, and having a true understanding of what someone who comes from poverty is experiencing — all without judging or looking down on them. So, that’s what I was looking for when I started thinking about the inaugural class for Charles Drew. With my colleagues, we were looking for stories and students to fill those needs and close that gap.

Offodile: One of the transformational things that many of our students possess is that they were those poverty-stricken patients going to see doctors in areas that were resource poor. The opportunity to help change that narrative in the next generation within your family, or in the community that you’re going to serve as a doctor — I think this is transformational. That’s the incoming class.

Q: How can you keep these students invested in the health workforce even as they face so many challenges as students within the overall health care industry?

Loeza: We’re focused on a little bit of encouragement every day, and we check on them. We’re both mothers, so we’re very motherly in our approach. I don’t think I ever spoke to the dean at my med school, but we talk with our students all the time. These students are already very motivated, and they know we love this job. A lot of things are hard about medicine, but being a doctor is still one of the best jobs in the world.

Offodile: Oh, yeah. I never spoke with the dean! [Laughter] I would never have gone to the dean’s office. No one in the dean’s office looked like me a decade ago. Both Dr. Loeza and I keep our doors open, and if we see somebody walking by, we wave them in and ask, “How are you doing?” It’s just that nurturing portion that we bring to the table that matters, but it’s not forced. When I see these young people, I see my own kids. I see the people I know in my community. And I’m so invested. I’m so proud. I think when you see people who look like you in your field, you’re less afraid. You feel that someone cares about you.

Q: What do you hope that leaders in education, health, and government will learn from Charles R. Drew University?

Loeza: That we need to invest in our community and our young people. We need to remove structural barriers to young people becoming doctors, financial or otherwise. That includes helping with networking, mentorship, and upfront costs for even the seemingly small items that cause financial stress for students, like food, books, and transportation. It shouldn’t be so hard to become a doctor, because creating doctors benefits everybody. It doesn’t only benefit the person going to medical school. So, we need to invest in our community because our community is desperate for these students to become doctors.

Offodile: Improving the health outcomes in this country means sharing the wealth and sharing the burden. It’s about sharing every part of what it takes for every person in this country to have adequate health care, appropriate educational opportunities, and sufficient employment. And it’s about erasing fear and bias. That’s true for medical education, too.

Q: What’s your wish for Charles Drew students and medical students in general who will be joining the health care workforce?

Loeza: I would like it to be better for our medical students than it was for us and for them to continue the work that we’re doing. In 30 years, I would like it if what this class and Charles Drew are doing is not so unique and that no one will be surprised when a Latina primary care doctor like myself or Black female surgeon like Dr. Offodile says they’re an associate dean or the assistant dean of a medical school. I hope that the women and the men in our class of color will have an easier path and that they will bring others up like them and mentor others. And I wish them so much happiness in their careers.

Offodile: My dream would be that any child — regardless of their race or what neighborhood they come from — who lives in poverty and lacks educational opportunities can still dream of becoming a doctor. The 60 people who have started at Drew are our children. They got two mamas in Dr. Loeza and me, and we are going to make sure that they’re going to have a better experience than we had. Then it’s going to be on them to make sure the next group of people who follow them have a better experience than they had. And we just keep it going — that’s my dream.

Authors & Contributors

Sarah Jimenez

Sarah Jimenez was a senior communications officer based in CHCF’s Sacramento office from 2023-2025.

Before joining CHCF, Sarah served as communications directors for the National Center for Youth Law and the California Budget & Policy Center. She was responsible for leading strategic communication initiatives with senior leadership and policy analysts and promoting the use of the organizations’ research and information in key policy discussions. She previously served as a senior strategist for Paschal Roth Public Affairs, working on statewide affordable housing and mental health voter initiatives. She also was the communications and outreach manager for the County Welfare Directors Association and assisted county human service departments in Affordable Care Act implementation.

Sarah holds bachelor of arts degrees in print journalism and gender studies from the University of Southern California.